THE CROWN RULE (1858-1947)

The Crown Rule refers to the British Raj or Direct rule in India. It was the time when the British power in India shifted from the East India Company to the British Crown. The Crown’s control over the Indian subcontinent from 1858 to 1947.

Since the Pitts India Act of 1784, the British parliament curtailed the power of the Company and eventually brought the Government in India under the British Crown. The whole process was completed with the Government of India Act 1858.

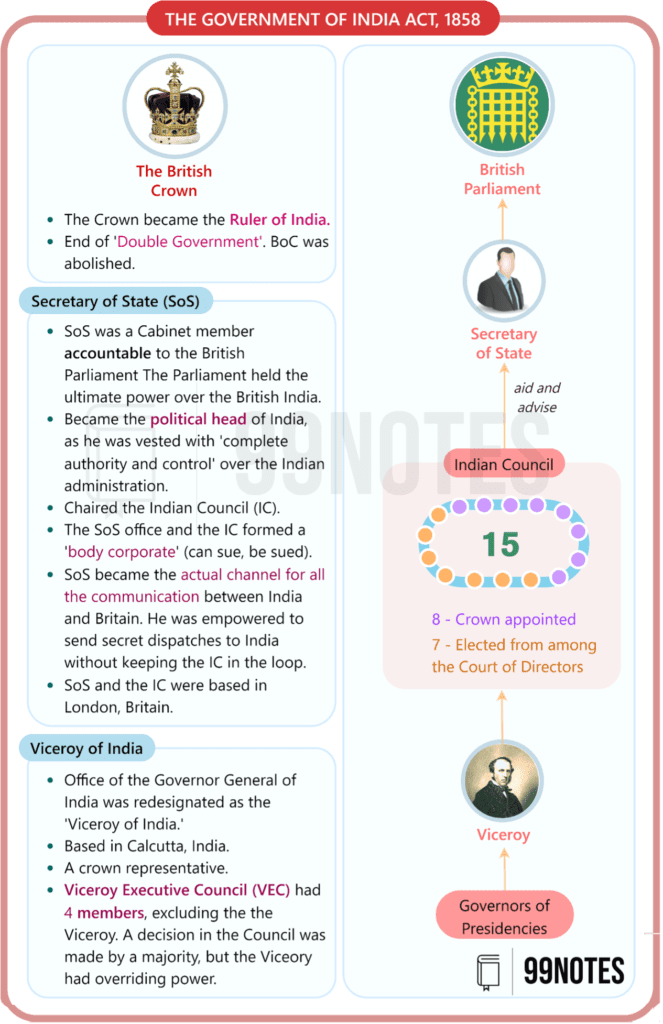

Government of India Act of 1858:

Background:

- The Government of India Act or the Act for the Good Government of India was passed after the Revolt of 1857, also referred to as the First War of Independence or the ‘Sepoy Mutiny’.

- The British Parliament had been looking to take control over India; the Sepoy Mutiny gave them the excuse to do so.

- The 1858 Act led to the dissolution of the East India Company. It transferred government powers, territories, and revenues to the British Crown, making it a pivotal moment in Indian history.

Features of this Act:

- It ended the Dual government scheme that was initiated by the Pitt’s India Act.

- The Company’s Court of Director’s powers were transferred to the Secretary of State for India. He was going to be a member of the British Parliament. He was provided with an advisory body consisting of 15 members.

- The secretary of state-in-council was made into a corporate entity with the ability to initiate and defend legal actions in India and England.

- A viceroy would be appointed to serve as the British Crown’s representative. Lord Canning was the first such Viceroy.

- India became a direct British colony through the passage of this Act.

- The Act ended the controversial ‘Doctrine of Lapse.’

- The Indian Civil Services was to be constituted for the country’s administration. There was also a provision for Indians to be admitted to the service.

- Indian princes were allowed to retain their principalities so long as they accepted the suzerainty of the British.

Criticism of the Act:

- It did not in any way alter the system of Government in India.

- Most of the provisions were enacted to safeguard the jewel of the British empire against any future threats or rebellions.

Indian Councils Acts

- Following the 1857 revolt, the British Government recognised the need to involve Indians in the administration of their country and sought their cooperation.

- The British Parliament passed three acts in 1861, 1892, and 1909 to implement their association policy. The Indian Councils Act of 1861 is important in India’s constitutional and political history.

Indian Councils Act 1861:

The Indian Councils Act of 1861 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that transformed India’s executive Council to function as a cabinet run on the portfolio system. It was introduced because the British Government wanted to involve the Indian people in law-making. This Act was passed on August 1, 1861.

Features of the Act of 1861:

- It made the beginning of representative institutions by associating Indians with law-making.

- Viceroy nominated some Indians as non-official members of his expanded Council.

- Lord Canning nominated – the Raja of Benaras, the Maharaja of Patiala and Sir Dinkar Rao.

- Provincial Legislative powers restored:

- Restored legislative powers of Bombay and Madras.

- Establishment of new Legislative councils for North-Western Frontier Province, Punjab and Bengal.

- Viceroy could make provisions for convenient transactions of the business in the Council.

- It gave recognition to the ‘portfolio system’ of Lord Canning.

- The Viceroy could issue ordinances without the concurrence of the Council during an emergency. However, the life of such an ordinance was six months.

Drawbacks of the Act:

- The biggest demerit of the Act was related to the selection and the role of the Additional Members.

- These members did not participate in the discussions; their role was advisory only.

- The non-official members of the Executive Council were not involved in attending the meetings of the Council. Furthermore, under this Act, they were not bound to follow them.

- The Indian members were not eligible to resist any bill, and mostly, the bills were passed in one sitting without discussion.

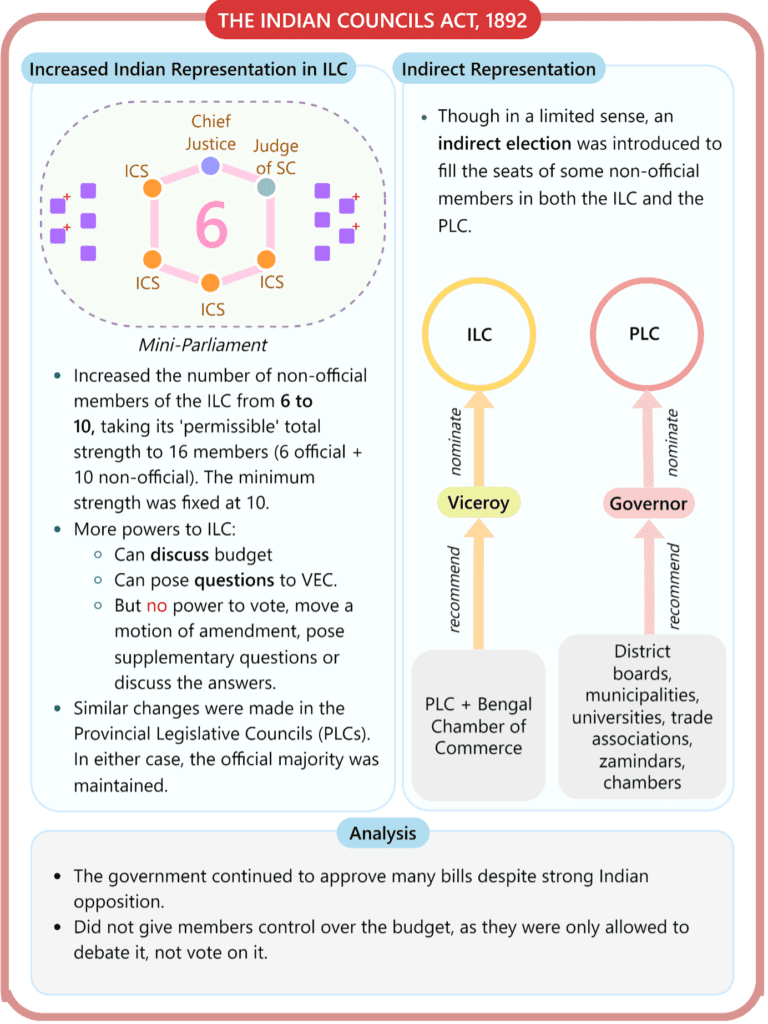

Indian Councils Act 1892:

The Indian Councils Act of 1892 was an Act of the British Parliament that inserted various changes to the composition and function of legislative councils in British India. Most notably, the Act expanded the number of members in the central and provincial councils.

Main provisions of the Act:

- Increased non-official members in the Council.

-

- Bombay – 8

- Madras – 20

- Bengal – 20

- North-Western province -15

- Oudh – 15

- Central Legislative Council minimum – 10, maximum 162

- Members could now debate the budget without having the ability to vote on it and be barred from asking follow-up questions.

- The Governor-General in Council was given the authority to set rules for member nomination, subject to the approval of the Secretary of State for India.

- Made a limited and indirect provision for using elections to fill up non-official central and provincial council seats.

- Nomination for non-official members to central legislative Council (Bengal Chamber of Commerce, governors for provincial legislative Council based on recommendation of district boards, municipalities, universities, trade associations, zamindars and chambers).

Significance of the Act:

- The Indian Councils Act 1892 is a significant milestone in India’s constitutional and political history.

- The Act increased the size of various legislative councils in India, thereby increasing the engagement of Indians concerning the administration in British India.

- The Indian Councils Act 1892 was the first step towards the representative Government in modern India.

- The Act created the stage for developing revolutionary forces in India because the British only made a minor concession.

Drawbacks of the Act:

The Act made a limited and indirect provision for using elections to fill some non-official Central and provincial legislative council seats. However, the word “election was not used in the Act. The process was described as a nomination made on the recommendation of certain bodies.

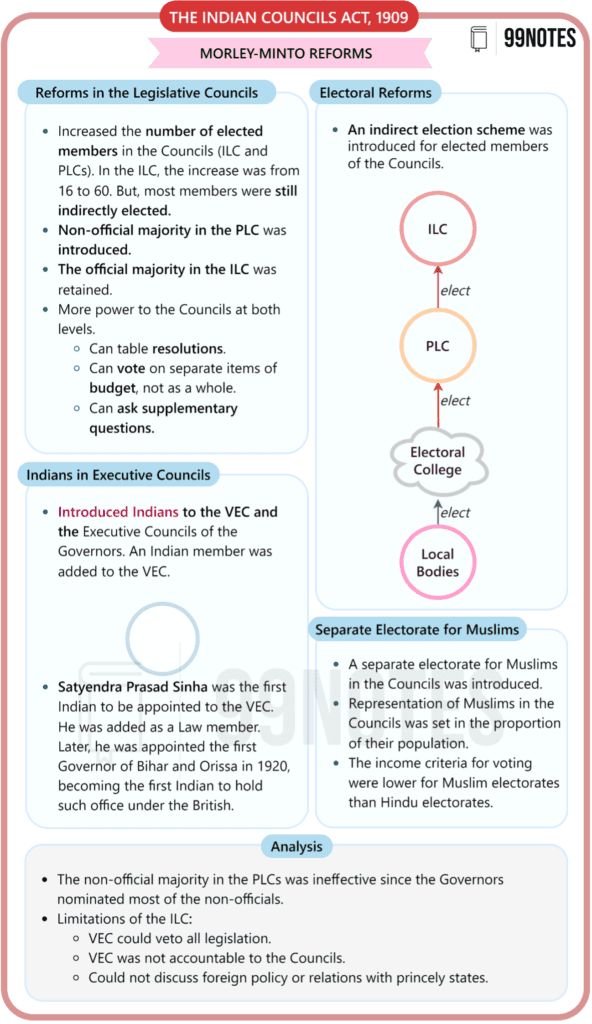

Indian Councils Act 1909:

This Act is also known as the Morley-Minto Reforms. It is one of the historic acts passed by the British parliament. Lord Morley was the Secretary of State for India, and Lord Minto was the Viceroy of India at that time.

Features of the Act of 1909:

- The legislative councils at the provinces and the Centre enlarge in size.

- It introduced a non-official majority at the provincial legislature level.

- It widened the deliberative work of the legislative councils of both levels.

- It provided for the first time for Indians to be associated with the Executive Council. Satyendra Prasad Sinha (SP Sinha) became a law member of the Viceroy’s Executive Council.

- Communal Electorate: It introduced a system of communal representation for Muslims under a separate electorate.

- Now, the Muslim members were to be elected only by Muslim voters. This way, Muslim leaders would now need no support from other populations. This meant that the more communal the leader, the more votes he could get without worrying about the general electorate.

- Thus, the Act ‘ legalised communalism’.

- Lord Minto, who introduced it, was known as the Father of Communal Electorate.

- Separate representations were provided for presidency corporations, chambers of commerce, universities and Zamindars.

Analysis of the Act:

- It sowed the seed for Partition in India.

- It belied the expectations of self-governance that Congress had sought.

- No meaningful representations at the central legislature level.

Government of India Act of 1919:

It laid the foundations for many features that we associate with the Indian constitution in the present times.

Background:

- The Indian leaders had pushed the British establishment for the Gradual introduction of responsible Government in India.

- The British Government had also promised the same in exchange for support for the 1st World War (1914-19)

- Thus, it was imperative for the Government to introduce responsible Government at some level. The GoI Act of 1919 introduced elected executives at the provincial level.

Features of the Act:

- Dyarchy in the Provinces:

- It relaxed the control of the Centre over the provinces by separating the central and provincial subjects.

- The provincial subjects were divided into Reserved and Transferred lists.

- Reserved lists were administered by the governor, and his executive Council was not answerable to the Legislature.

- In contrast, the assigned lists were issued by the governor on the advice of the ministers responsible to the Legislative Council.

- Bicameralism and direct elections were introduced.

- More Indians in Executive Councils: The Act mandated that three of the six members of the Viceroy’s Executive Council were to be Indian.

- Expansion of Communal Electorate: The principle of separate electorates was extended to Sikhs, Indian Christians, Anglo-Indians and Europeans.

- It granted franchises to a limited number of people based on property, tax or education.

- A high commissioner of India position was created. Some powers of the Secretary of State were transferred to the commissioner.

- Provincial budgets were separated for the first time from the central budget.

- Central public service commission was established.

- A Statutory commission was to analyse the impact of this Act after 10 years.

Simon Commission

Background

- In November 1927, the Government of British India declared the establishment of a Statutory Commission headed by Sir John Simon.

- The objective was to access the Montagu Chelmsford Act, aka GoI Act of 1919. In 1930, the commission submitted its Report.

- A law was needed to define governance mechanisms in Burma was included in its program.

AIM OF THE COMMISSION/TERMS OF REFERENCE:

- To abolish the diarchy that was established in the 1919 Act.

- An extension to the autonomy of provinces by establishing a responsible government.

Major recommendations

- Abolition of dyarchy at the Provincial Level and the extension of responsible Government in provinces.

- Continuation of communal representation in India.

- Establishment of a federation of British India and princely states.

Communal Award:

- The Communal Award was a promise of a separate electorate to the depressed classes and minorities. It meant that the general electorate people couldn’t vote for the depressed-class candidate. This would have created a huge divide in the ‘Hindu’ Community.

- British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald created it on 16 August 1932 and therefore came to be known as the MacDonald Award.

- It was born as a result of the second-round table conference, in which leaders like Ambedkar supported this move.

- Gandhi sat on a Satyagrah to convince Ambedkar to at least have a general electorate, despite having a reservation of seats.

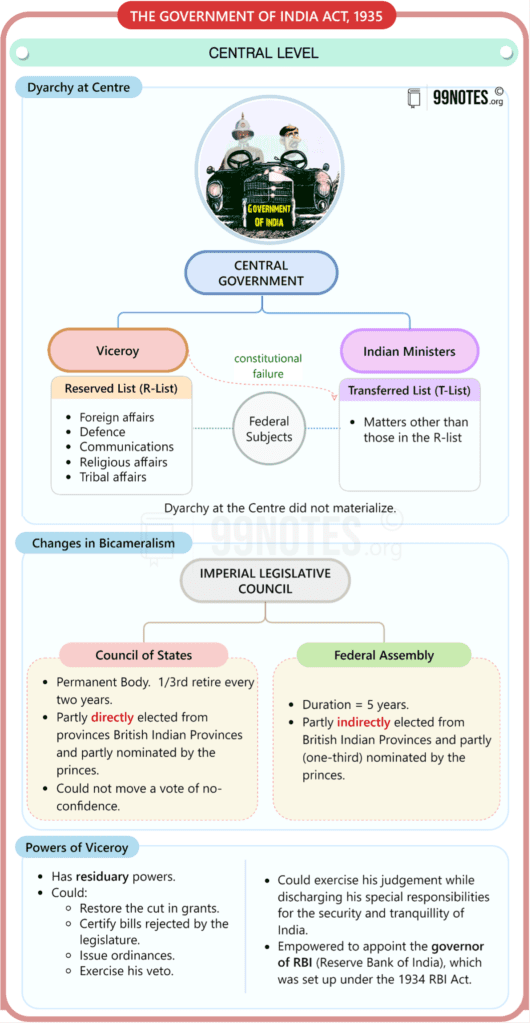

Government of India Act of 1935

The Act marked a second milestone towards an ultimately responsible government in India. It was a lengthy document with 321 Sections and 10 Schedules.

Features of the Act

- Introduction of Federalism:

- It provided for establishing an All-India federation consisting of provinces and princely states as its respective units.

- It divided the powers between the Centre and units into three lists- Federal, provincial, and concurrent. Residuary powers were given to the Viceroy.

- However, this federation never fructified since princely states did not join it.

- Fully Responsible Government in the Provinces:

- It abolished the dyarchy in the provinces and introduced ‘provincial autonomy’.

- The Act introduced responsible Government in provinces; i.e., the governor was required to act with the aid and advice of the ministers responsible to the provincial Legislature.

- Diarchy at the Centre:

- It provided for the adoption of dyarchy at the Centre.

- The Viceroy of India had some reserved subjects for which he wasn’t answerable to the Legislature.

- While some subjects were transferred to the elected ministries, which were answerable to the Legislature.

- However, this provision did not come into effect at all.

- Bicameralism was introduced in six provinces– Bengal, Bombay, Madras, Bihar, Assam and the United Provinces.

- Communal Award: Separate electorates were further extended to depressed classes, women and labour.

- Council of India, established as per the 1858 act, was abolished. The secretary of state was instead provided with a team of advisors.

- The Act provided for setting up- the Federal public service commission, provincial public service commission, Joint public service commission, Federal court, and Reserve Bank of India.

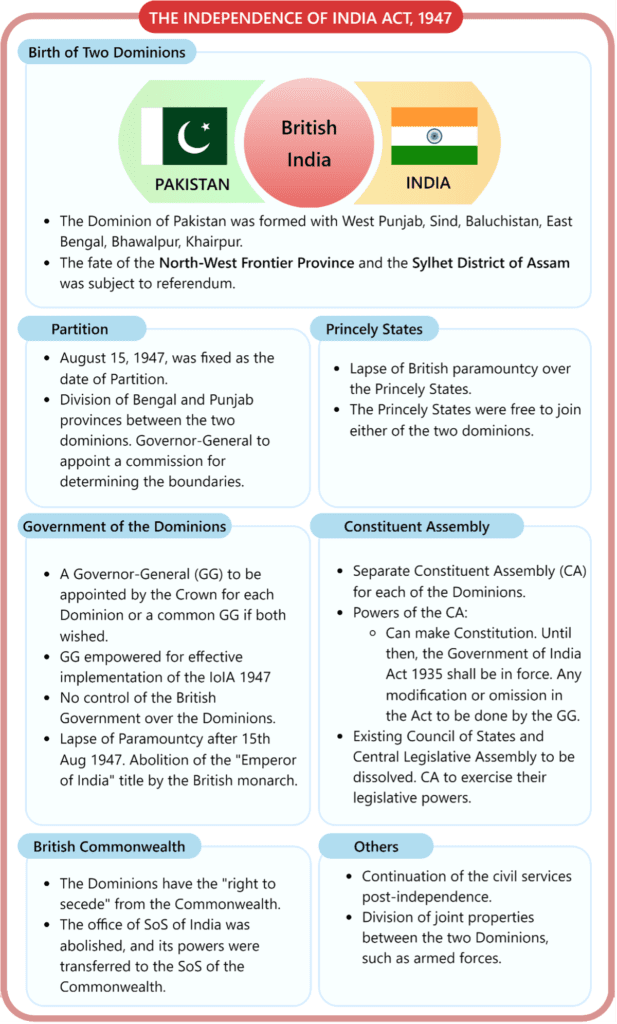

Indian Independence Act of 1947

The Indian Independence Act of 1947 was crucial because it enabled the transfer of power from the Crown to India in an amicable manner. It was passed in British Parliament on July 5 of that year and received royal assent on July 18. A plan was formulated to split the British Indian colonies into India and Pakistan by Viceroy of India Lord Louis Mountbatten and Prime Minister of Britain Clement Attlee on June 3, 1947, after consultations with the main stakeholders — Indian National Congress, the Muslim League and representatives of the Sikh community.

Salient features of the Indian Independence Act 1947 are:

- It declared India as an independent and sovereign state.

- Abolished Colonial offices:

- It abolished the position of secretary of state for India.

- It abolished the Viceroy’s office and provided each dominion with a governor-general, who the British King would appoint on the advice of the dominion cabinet.

- Creation of two Independent Dominions:

- It provided for the Partition of India and the creation of two new dominions – India and Pakistan.

- Governance of each dominion was to be conducted based on the provisions of the GoI Act, 1935

- Creation of two constituent Assemblies:

- It allowed the constituent assemblies of the two dominions to frame the constitutions for their respective nations and empowered them to repeal any act of the British parliament, including the independence act itself.

- Note: Initially, members were elected to form only one constituent assembly, but when India was partitioned, the constituent assembly was partitioned too.

- Constituent assemblies were empowered to legislate for their respective dominions till the new constitutions were enforced.

- Abolition of Paramountcy in princely states: It granted the princely states the freedom to join dominions or remain independent.

- The office of the Governor-General

- The Governor-General of the dominions was made to act on the aid and advice of the Council.

Criticism of the Act:

- Hastened Act: the lack of clarity on the border still has repercussions today with the constant tussle between India and Pakistan. The same is the case with the border on the Chinese side.

- Clarity on the Question of Princely states: The Act made it possible for the Princely states to remain independent, introducing confusion in an already tense environment. This created a problem of unification in the context of Hyderabad and Jammu & Kashmir.

- Rise in communal feeling: Another unforeseen consequence of Partition was that Pakistan’s population became more religiously homogeneous than initially anticipated.

- Suspicion: Indian Muslims are frequently suspected of harbouring loyalties towards Pakistan; non-Muslim minorities in Pakistan are increasingly vulnerable thanks to the so-called Islamisation of life there since the 1980s.

Conclusion

Post-partition fragmented identities strengthened, and the much-celebrated value of tolerance and acceptance appears to have weakened, disturbing social harmony in the country. The exploitation of religious sentiments for political gains has further polarised society.