Budget in Parliament UPSC Notes

The Budget is an annual financial statement giving an account of the expected revenue and expenditure of public money in a financial year, which starts on 1st April and ends on 31st March. It is a work plan that gives direction to the implementation of policies and programmes.

Note:

- The Constitution does not mention the term ‘Budget’; it uses the term ‘Annual financial statement’ in Article 112.

- The Finance ministry prepares the annual Budget in consultation with every other ministry.

Necessity of the Budget:

Even though the government is empowered to take any executive action in the country, it cannot be done irresponsibly. The Constitution empowers the Parliament to keep a check on the Executive. All the expenditure done by the government is checked through two mechanisms:

- Prior approval of the Parliament: No expenditure can be made by the government unless the Parliament approves it, and no tax can be introduced unless the Parliament approves it.

- Scrutiny of Financial decisions already taken: Through various Parliamentary committees and audit reports of the CAG, the members of Parliament are equipped with adequate resources to scrutinise all the previous financial decisions of the government.

In recent years, new mechanisms have been added by the Parliament to ensure fiscal responsibility and that the governments do not borrow too much.

| A Lesson from History: Evolution of Budget in India |

| The first formal Budget was presented in 1860 by Sir James Wilson, the then finance minister of the Governor General Council. At that time, there was no elected legislature to scrutinise the Budget.

1. The discussion over the Budget by the members of the central Legislative council only started in 1892. 2. The Government of India Act 1919 separated the central Budget and provincial Budget. Further, in 1924, the Railway Budget was separated from the general Budget on the Ackworth’s committee’s recommendation. 3. Independent India’s first Budget was presented in November 1947 by then-finance minister R K Shanmukham Chetty. 4. In 2017, the railway budget and general Budget were merged as their relevance reduced significantly on account of their significantly shrunk size. Since 2017, the Union budget has been presented on 1st February; earlier, it was presented on the last day of February. It was shifted so that the Budget could be effectively implemented before the start of the financial year. |

What constitutes the Budget?

The Budget essentially consists of two accounts:

- Estimates of receipts (both revenue and capital) and ways and means to raise the revenue;

- Estimates of expenditure;

Apart from these, the Budget also contains:

- Account of receipts and expenditures in the closing financial year. This is to ensure accountability before the Parliament, where members of Parliament can discuss about the prudence of previous expenditure.

- It also contains the vision behind the economic and financial proposals for the upcoming financial year, which include taxation proposals and reforms, the introduction of new welfare schemes, etc.

We shall discuss the Budget documents later in this article.

Annual Financial Statement:

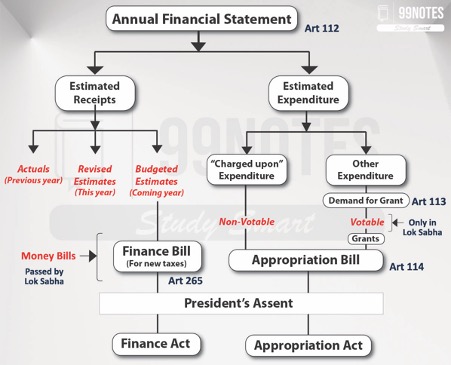

The Union budget is technically known as the Annual Financial Statement, as addressed in Article 112 of the Constitution. It is a statement of the estimated revenues and expenses of the Government of India, which the President is bound to place before both Houses of Parliament each fiscal as per Article 112.

Thus, for its systematic understanding, we should also break the Budget into two parts:

- Estimated Expenditure

- Estimated Receipts

Here, it must be noted that all revenue receipts earned by the government through various means, such as taxes, form part of the Consolidated Fund of India, and all expenditure done by the Government of India is appropriated out of the Consolidated Fund of India.

1. Estimated Expenditure:

Article 112 mandates that the government should show two types of expenditure separately in the Annual financial statement:

- Expenditures that are already “charged upon” the consolidated fund of India. It includes the salaries of all the constitutional authorities like the President, Vice-President, Speaker, Judges of the Supreme Court, CAG, etc. It can also include grants to the states and expenditure on certain government schemes as declared by Parliamentary law.

- Expenditures that are “proposed to be made” from the consolidated fund of India must be shown separately.

This distinction is important because expenditures that are charged upon the consolidated fund of India, such as salaries of important constitutional offices, their pensions, statutory grants and schemes, etc., should run smoothly without the need for approval every year. Thus, Article 113(1) says that all the expenditures that are already charged upon the consolidated fund of India shall not be put to the vote of Parliament.

However, for all other expenditures, the government must be answerable to the Parliament. Thus, this creates a distinction between “Votable and Non-Votable expenditure”. The expenditure already charged upon is votable, and all other expenditures are non-votable.

| Non-Votable expenditure | Votable Expenditure |

| The expenditure “charged upon” the consolidated fund of India is not put to the vote each year. | “Other expenditures” for which demand for the grant has to be put before the Parliament, and the Appropriation Act has to be passed. |

| It generally includes constitutionally mandated expenditures such as salaries of constitutional offices and grants-in-aid. | It includes all other types of expenditure that the government wishes to make, such as salaries of officers and employees and expenditure on schemes and government programs. |

This appropriation for the votable expenditure is done in the following manner:

Step 1: The Government puts a Demand for a Grant

Step 2: These demands are introduced in the Parliament as Appropriation bills, along with the “Charged” expenditure.

Step 3: If passed by the Lok Sabha, these “Appropriation Acts” enable the government to appropriate the said amount out of the consolidated fund.

Demand for Grants (Article 113)

In order to perform any expenditure (apart from the charged expenditure), the government has to first make the demand for money from the Consolidated Fund of India.

- Article 113 (2) says that each estimate of expenditure shall be put before the Lok Sabha as a “Demands for Grants” separately; the House is empowered to approve or reject any demand or to approve a demand with a reduction in the specified amount.

- Article 113 (3) further says that all such “demands for grants” shall be made with the prior recommendation of the President. This is done to enable only the government, not a private member, to make such demand for a grant for an expenditure.

Appropriation bill (Article 114)

The “Demands for Grants” made by the government is introduced in the Lok Sabha as an Appropriation bill.

- Article 114 (1) says that as soon as the demand for a grant is made in Lok Sabha, an appropriation bill shall be introduced to appropriate money out of the Consolidated Fund of India.

- This is a necessary step, as Article 114 (3) further states that no money shall be withdrawn from the Consolidated Fund of India except under appropriation made by law. This role is fulfilled by the ‘Appropriation Bill’.

An appropriation bill is a money bill, and therefore, the Rajya Sabha has limited power in this regard, as it can discuss the provisions of the Budget but cannot vote on the demands for grants.

Once passed, it becomes an Appropriation act that enables the government to function and spend money.

2. Estimated Receipts:

The receipt side of the Budget mainly shows three items:

- Estimated Tax revenue, which includes revenue from all major taxes.

- Estimated Non-tax revenue, which includes the interest receipts, profits and dividends from the government-owned institutions, fees and fines collected by various departments, etc. It also includes all the grants-in-aid received from various foreign countries and banks.

- Estimated Capital receipts, which include recovery from loans, government borrowings (internal and external), and draw down of cash balance.

These items are estimated for 3 consecutive years:

- Budgeted Estimate (BE) for the forthcoming year for which the budget document is being presented. This may include changes in the tax structure, which is done via a Finance bill.

- Revised Estimate (RE) for the ongoing year, which is about to end and for which a budget was presented last year. The government tells the Parliament about the estimated tax that it would receive according to the calculations done by the Finance ministry.

- Actual Receipt for the year bygone. The government tells about the actual tax that it received for the last budgeted year.

(Example of the estimated ReceiptReceipt)

Finance Bill

For the Budgeted year, the government might introduce a new tax to raise its revenue. This can only be done if the Parliament passes a law to this effect.

Article 265 says that “No tax can be imposed except by authority of law.” Thus, in order to introduce a new tax, the government has to pass a law. This is generally done through the Finance Bill, which, when passed by the Parliament, becomes the Finance Act. It passes as a money bill.

Note: If the government wishes to continue with the old tax scheme, it requires no new finance bill. Tax would be levied based on the previous year’s finance act.

All the changes in the tax rates, new deductions and rebates, introduction of new taxes, etc., are done through the Finance Act. (Example of a finance bill)

Funds of India

To manage all accounts of receipts and payments, the Constitution provides for 3 types of funds for the Central government.

1. Consolidated Fund of India

Under the provision of Article 266 of the Constitution, the consolidated fund of India consists of:

- All the revenue received by the government – This includes revenue from all the taxes (tax revenue), as well as non-tax revenue collected as duties, fees, fines, and profit from government-owned companies, etc.

- Loans raised by the government either through the issue of treasury bills and bonds or through any other means and

- Receipts from recoveries of advances granted by it. For example, the interest payments on loans given to the states or to other countries.

This means all major funds received by the government form part of the Consolidated fund of India.

Article 266 further states that no amount can be taken out from the fund without authorisation from the Parliament (i.e. through an appropriation act). This enables Parliamentary oversight over all the money spent by the government as salaries, on government schemes, and loans given to different entities, etc.

2. Public fund of India

The government can receive some other kinds of funds on behalf of the public or some other entity, for example, provident fund (PF) deposits, small saving deposits, judicial deposits, etc, which it might to repay at any time. It cannot spend these sums in the same way as the funds received as taxes. Therefore, these are not made a part of the Consolidated fund of India.

For this, Article 266 provides for a Public fund of India to receive “all other public money” received on the behalf of the government. This account is operated by executive action, which means Parliament’s authorisation is not required. This enables the government to pay the public its due amount whenever the public demands, without the Parliament’s permission.

3. Contingency Fund of India

The Constitution provides for the Contingency fund of India under Article 267. This fund has been made to meet the urgent unforeseen expenditure during a crisis, for example, a natural calamity.

This fund does not require authorisation from the Parliament; it is placed at the disposal of the President, and the finance secretary in the Government of India administers it.

In FY22-23, the corpus of the fund was increased from ₹500 crores to ₹30000 crores. This increased sum was necessary given the increasing security needs of the nation, although it reduces Parliamentary oversight.

Nevertheless, an increased Contingency fund does not mean that the fund remains unaccountable. The expenditure is still audited by the CAG and is reported to the Parliament each year as a part of its annual report.

Charged Expenditure

Now, we understand that the Parliament has limited authority over expenditure charged on the consolidated fund of India, as it can only be discussed but cannot be voted upon.

This method of having a ‘consolidated fund’ and charging certain expenditures on it originated in the Westminster (British) model. It includes the expenditure made on important constitutional and statutory offices to ensure their independence from the legislature and the ruling party.

In the Indian Constitution, Article 112 mentions the following expenditure to be charged upon the consolidated fund of India:

- Emoluments of the President;

- Salaries and allowances of the chairperson and the deputy chairperson of the Rajya Sabha;

- Salaries and allowances of Speaker and deputy speaker of the Lok Sabha;

- Salaries, allowances and pensions of Supreme Court judges;

- Salaries, Allowances and pensions of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG), Chairman and members of Union Public Service Commission (UPSC);

- Administrative expenses of the office of Supreme Court, CAG and UPSC, it also includes salaries, allowances and pensions of these employees;

- Interest on and repayment of loans raised by the government;

- Payments made to satisfy decrees of courts;

- Grants-in-aid are given under Article 275, including the schemes made for tribal areas and ST communities.

- Any other expenditure declared to be “charged upon” on the Consolidated fund by the Constitution or any Parliamentary law.

The Parliament has, through law, made interest payments and a few schemes charged upon the consolidated fund.

Stages of a Budget

Budget enactment goes through various processes in the Parliament; these have been discussed below:

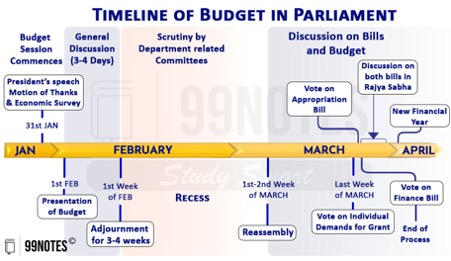

1. Presentation of the Budget

The Budget in Parliament is presented by the Finance Minister on a date fixed by the President. Since 2017, it has been presented on 1st February.

After the speech is concluded in the Lok Sabha, the annual financial statement (Budget) is laid in the Rajya Sabha. It is to be noted that the Rajya Sabha can only discuss the Budget and cannot vote on the demands for grants.

2. Budget Documents

Through annual financial statement (i.e. the Budget), the government presents the following documents:

- Annual Financial statement – consisting of estimated expenditure and estimated receipts.

- Demands for grants: It contains ministry-wise demands of various departments of ministries.

- Appropriation bill: It authorises the government to withdraw funds from the consolidated fund of India for that financial year.

- Finance bill: It deals with taxation proposals of the government.

- Outcome Budget: it deals with the performance of ministries in the implementation of policies, schemes and expenditure incurred by them.

- Documents mandated under the FRBM Act:

- Macro-Economic Framework Statement

- Medium-Term Fiscal Policy Statement

- Fiscal Policy Strategy Statement

The Budget is discussed in Lok Sabha in two phases; in the first phase, general discussion takes place.

3. General Discussion on Budget

The general discussion takes place a few days after the presentation of the Budget and lasts for about 3-4 days. In general discussion, only the broad outlines of the Budget and underlying principles and policies are discussed. At this stage:

- No cut motion can be moved,

- Nor is the Budget voted by the House.

- At the end of the discussion, the Finance Minister has the right to reply.

4. Consideration of demands by departmental standing committees

After the general discussion on the Union budget is over, the House is adjourned for a fixed period of time (generally, three to four weeks). During this period, the demands for grants of ministries are considered by concerned committees. These committees are required to make a report to both Houses within a specified period of time.

- The system of department-related committees was introduced in 1993; earlier, there were 17 such committees, then they were expanded to 24 in 2004. These committees have 31 members (21 from Lok Sabha and 10 from Rajya Sabha).

- They make financial control of the Parliament more comprehensive and robust.

5. Discussion and vote on demands for Grants

After the standing committees present their report, the Lok Sabha takes up the discussion and votes on the demands for grants. Rajya Sabha only takes part in the general discussion; it does not vote on the demands for grants. At this stage, a detailed discussion of demands takes place.

- The demands are presented ministry-wise, and each demand is voted on separately; they become grants after they are duly voted.

- It is to be noted that no voting takes place on ‘expenditure charged on the consolidated fund of India’.

- The Lok Sabha can criticise the demands, reduce them, or reject them but cannot increase It should be noted that demands for grants can only be made on the recommendation of the President.

- The voting on demands for grants must be completed within a fixed time limit (decided by the Speaker in consultation with the Leader of the House). On the last day, all the remaining demands are put to vote, even if they have not been adequately discussed. This process is known as ‘Guillotine’.

6. Cut Motions

The members can move cut motions to express disapproval towards budgetary provisions. Even though such motions never get passed, as the government has a majority in the Lok Sabha, they provide constructive criticism on specific provisions of the Budget.

There are various types of cut motions, which have been listed below:

- Policy Cut motion: Through this, the members can express their disapproval towards the policy underlying the demands. The motion states that the demand be reduced to ₹1. The members can also suggest an alternative policy.

- Economy Cut Motion: This motion states “that the amount of the demand be reduced to a specified amount”. Such specified demand may consist of a one-time reduction in the demand or omission or reduction of an item in the demand.

- Token Cut Motion: This motion states that the amount of the demand be reduced by ₹100. This motion is moved to register specific grievances which fall within the purview of the government of India.

7. Appropriation Bill

After voting on the demands for grants is finished, the government introduces the Appropriation Bill. An appropriation bill authorises the government to withdraw funds from the consolidated fund of India.

- The appropriation bill contains the grants voted by the Lok Sabha and the expenditure charged on the consolidated fund of India.

- No amendment can be proposed in either the House of the Parliament, which varies the amount of any demand or varies the amount charged on the consolidated fund of India.

- The process of passing an appropriation bill is similar to that of a money bill. It is certified as a money bill by the Speaker.

Finance Bill

The financial bill seeks to give effect to the taxation proposals of the government.

- It is introduced on the day of the budget speech However, it is taken up for consideration by the Lok Sabha after the appropriation bill is passed.

- Some provisions related to fresh duties and variations in previous duties come into effect just after the expiration of the day on which the bill was introduced.

- The Parliament is required to pass the bill and get the assent of the President within 75 days of its introduction.

- The process of passing the finance bill is similar to a money bill. Like an appropriation bill, a Finance bill is also certified as a money bill. Hence, the Rajya Sabha can recommend amendments, but it is up to the Lok Sabha to either reject it or accept it.

The passing of the finance bill marks the end of the budgetary process in the Parliament.

| Budget of States under President’s Rule |

|

Grants other than Budgeted

Suppose the government needs to perform an expenditure in the middle of a financial year. It would be impractical to present a full budget again to consider just a few demands for grants.

For such a situation, the Constitution allows the Parliament to provide the following grants:

- Supplementary Grant: When the government needs excess grants over and above the amount granted in the appropriation act for a service (say a scheme), a supplementary estimate is laid before the Parliament.

- Additional Grant: If the government has introduced a new service in the Budget but did not provide enough funds for it in the appropriation act, then additional demand can be granted through additional grants. For example, suppose a new scheme is proposed in the Budget in a hurry by the government, and there isn’t enough time to calculate the exact expenditure. Then, the scheme is introduced with a lump sum of a small amount in the Budget, and additional sums are granted for it later on.

- Excess Grant: If any money is spent on a certain service in excess of the amount granted for that service in a financial year, the Finance Minister presents a demand for the excess grant (post-facto approval). However, before presenting the demand for an excess grant before Lok Sabha, it must be approved by the Public Accounts Committee.

- Token Grant: Under this motion, the funds to meet the proposed expenditure on a new service can be made available by re-appropriation (transfer of funds from one head to another). A demand for the grant of a token sum may be put to the vote of the House, and if the House agrees to the demand, funds may be made available. It does not involve any additional expenditure.

- Exceptional Grants: If a completely new service is to be introduced by the government outside the Budget, the Parliament is empowered to pass an exceptional Grant.

- Vote of credit: It is granted to meet some unexpected demands, which, due to their indefinite character, cannot be stated in detail. It is considered a blank cheque given to the Executive. It could be a part of an ‘interim Budget’.

- Vote on Account: It is granted when the government requires an advance sum for part of a financial year (say for 2-3 months) before the appropriation act is passed by the Parliament. For example, the demand for grant and the appropriation act take around two months to be passed by the Parliament. If the government want to run the ministries according to the new Budget, the Parliament can pass a ‘Vote on Account’ so that the government can function for the time being.

| For your information |

| Article 115 talks about supplementary, additional and excess grants.

Article 116 talks about Votes on account, votes of credit and exceptional grants. |

| Did you Know? |

| In India, the financial year is taken as 1st April to 31st March. Before 2017, the Budget was introduced only at the end of February, and the demand for grant could be passed only after two months. This meant that the expenditure in the new financial year (from 1st April) had to take place before an appropriation act was passed. Therefore, the vote-on-account mechanism was used to enable expenditure before the passage of the Budget.

Since 2017, the budget presentation has been shifted from the last day of February to the first day of February; hence, a vote of account is no longer needed. Currently, only state governments use this mechanism. |

Interim Budget

When there is no time to prepare a full budget, the governments present an interim budget. It is presented under the provisions of Article 112 itself and thus provides estimates of revenue and expenditure just like a full budget. However, it generally does not include big policy decisions.

The Interim Budget is generally presented in the fiscal year in which general elections happen. This mechanism enables the government to function in various situations:

- A recently sworn-in government could spend as per its own wishes until a full budget is passed.

- An outgoing government, too, might choose not to pass a full budget, as was done before the 2019 general elections.

The interim Budget may even use the ‘vote on account’ mechanism to plan for the time until a full budget is passed.

| Interim Budget | Vote on Account |

|

|

Conclusion: In this article, we studied the constitutional provision regarding the Union budget. We shall study the economic concepts related to the Budget, the taxes therein, and the recent reforms in detail in the Economics section.