6 November 2024 : Indian Express Editorial Analysis

1. A Positive Secularism

(Source: Indian Express; Section: The Ideas Page; Page: 11)

| Context: |

| The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the UP Madarsa Act, affirming minority rights to religious education while clarifying the limits of the Basic Structure doctrine in assessing ordinary laws. |

What is the UP Madarsa Education Act 2004?

- Governs madarsas: The Act governs the education provided in madarsas – institutions which offer education that integrates religious teachings with some elements of modern, secular subjects, though religious instruction takes precedence.

- Established the UP Board of Madarsa Education:

- This board, predominantly composed of members from the Muslim community, is responsible for preparing curriculum and conducting examinations for various madarsa courses, ranging

- From ‘Maulvi’ (equivalent to Class 10)

- To ‘Fazil’ (equivalent to a Master’s degree).

Supreme Court Overrules Allahabad High Court on UP Madarsa Act

- The three-judge bench of the Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, recently stayed and subsequently overruled the Allahabad High Court’s decision regarding the Uttar Pradesh (UP) Madarsa Act, 2004.

- The verdict in the case of Anjum Qadri and Anr vs Union of India & Ors upheld the constitutionality of the Act, bringing a substantial relief to madarsas across the state and benefiting thousands of students enrolled in these institutions.

- The ruling underscores the balance between religious and educational rights, while reaffirming that the state’s regulation of madarsas does not infringe upon secularism, a core aspect of India’s constitutional framework.

Application of Basic Structure Doctrine

- A significant aspect of the ruling was the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Basic Structure doctrine, which preserves certain fundamental principles of the Constitution.

- The Court rejected the High Court’s use of this doctrine to challenge the UP Madarsa Act. Citing the Indira Nehru Gandhi judgment (1975), Chief Justice Chandrachud emphasized that the Basic Structure doctrine is only applicable to constitutional amendments, not to ordinary legislation.

- As such, the Supreme Court concluded that assessing an ordinary law, like the Madarsa Act, should focus on legislative competence and adherence to fundamental rights rather than abstract constitutional principles like secularism, democracy, or federalism.

Secularism and State Regulation of Religious Education

- The Court also delved into the concept of secularism, central to the High Court’s rationale for striking down the Act. Referring to the S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994) ruling, the Supreme Court explained secularism as “equal treatment of all religions” and a positive principle that supports religious tolerance by the state.

- Articles 25 to 30 enshrine rights allowing religious minorities to manage educational institutions, reinforcing that the state’s recognition and regulation of madarsas align with secular values rather than contradict them.

- This, the Court reasoned, signifies a proactive effort to safeguard the educational rights of religious minorities under a secular state framework.

Minority Rights and State Control over Educational Institutions

- A cornerstone of the judgment is its affirmation of minority rights under Article 30, which allows religious and linguistic minorities to manage educational institutions.

- The Court upheld that the state’s regulatory authority cannot infringe on the fundamental character of minority institutions. It clarified that while minorities may not inherently have rights to state aid or affiliation, the state’s support should not be conditional on undermining the institution’s minority character.

- This principle may have future implications, particularly concerning the ongoing debate over the minority status of Aligarh Muslim University.

Balancing Religious Education with Article 21A

- Addressing the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights’ (NCPCR) concern over madarsa education quality, the Supreme Court emphasized that the Right to Education (RTE) Act does not apply to minority institutions, a position it adopted in Pramati Educational and Cultural Trust v. Union of India (2014).

- The Court argued that Article 21A, mandating education for children aged 6-14, does not necessitate madarsas’ alignment with secular educational standards since their focus remains theological.

- The judgment implicitly recognized the diversity in educational pursuits, affirming the right of students to opt for theological studies and relieving madarsas from mandates aimed at secular institutions.

Religious Instruction, Secular Education, and Article 28

- The judgment also addressed the distinction between religious instruction and religious education. Article 28 of the Indian Constitution prohibits religious instruction in state-funded institutions but does not forbid religious education.

- The Court highlighted this distinction, particularly relevant to government-mandated religious activities. The ongoing Public Interest Litigation (PIL) by Veenayak Shah, challenging mandatory Hindu prayers in Kendriya Vidyalayas, underscores the importance of this debate on secularism and religious practices in education, echoing the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Engel v. Vitale (1962) against official prayers in public schools.

Recognition of Madarsa Degrees and Higher Education Access

- A minor setback for madarsas is the non-recognition of Fazil and Kamil degrees under the UP Act, due to the precedence of the University Grants Commission (UGC) Act, 1956.

- Although certain universities accept these degrees for specific theological courses, broader recognition in mainstream disciplines remains restricted.

- The Court suggested that this exclusion should not block madarsa graduates from higher education, emphasizing that educational pathways should remain open to those pursuing advanced studies in theology, Arabic, and Islamic Studies.

The Supreme Court’s judgment is a reaffirmation of minority educational rights within a secular framework, highlighting the importance of equal treatment and tolerance in a diverse society.

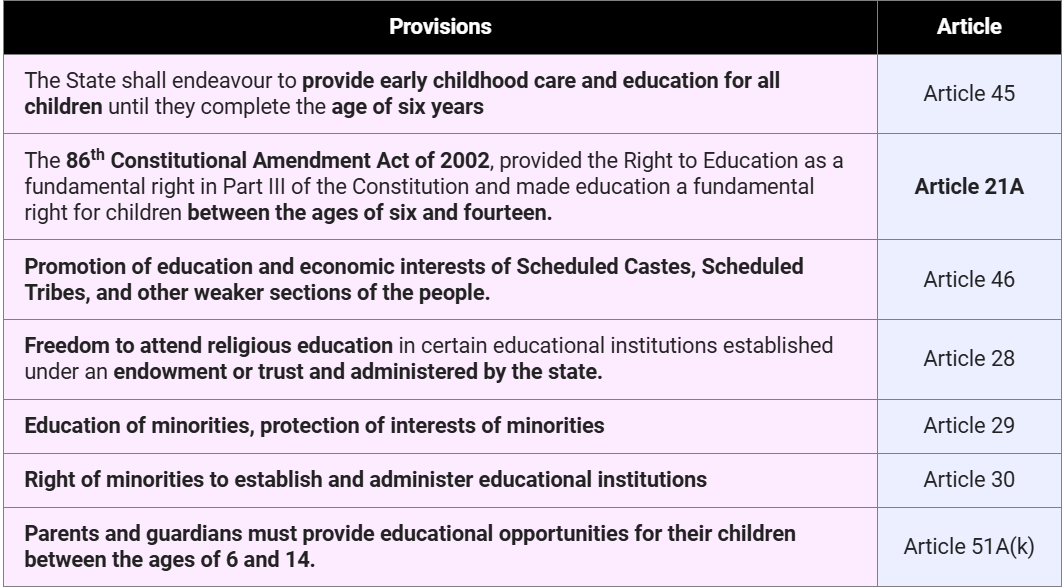

| What are the Constitutional Provisions Regarding Education in India? |

|

|

PYQ: Which of the following provisions of the Constitution does India have a bearing on Education? (2012) 1) Directive Principles of State Policy 2) Rural and Urban Local Bodies 3) Fifth Schedule 4) Sixth Schedule 5) Seventh Schedule Select the correct answer using the codes given below: (a) 1 and 2 only (b) 3, 4 and 5 only (c) 1, 2 and 5 only (d) 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 Ans- (d) |

| Practice Question: Discuss the significance of the Supreme Court’s recent judgment on the UP Madarsa Act. How does this decision impact the regulatory framework for minority educational institutions in India? (250 words/15 m) |

2. Bad Weather Friends

(Source: Indian Express; Section: The Ideas Page; Page: 11)

| Topic: GS3 – Environment – Environmental pollution and Degradation |

| Context: |

| The Chief Minister of Pakistan’s Punjab has called for joint efforts with India to tackle worsening pollution and climate challenges, highlighting the urgent need for cross-border collaboration on shared environmental issues. |

Urgency of Collaborative Efforts to Combat Pollution

- The Chief Minister of Pakistan’s Punjab province has underscored the critical need for India and Pakistan to jointly address escalating pollution and smog in the region.

- Despite existing climate-related efforts, these environmental challenges are inherently transboundary, demanding solutions that cross the political boundaries.

- Environmental issues today are no longer distant projections; they tangibly affect millions of lives across both nations. Shared geographical features, water sources, and air patterns make it impossible for India and Pakistan to tackle these issues independently, highlighting the need for cooperative measures that can effectively mitigate pollution.

Air Pollution and Shared Airsheds

- India and Pakistan share multiple major airsheds, where pollutants from sources like crop burning and festivals are carried across borders. Cities such as Delhi and Lahore, within these airsheds, suffer significant health impacts from increased levels of pollutants like PM 2.5 and PM 10.

- These pollutants exacerbate respiratory issues, place an immense burden on healthcare systems, and contribute to economic losses, such as India’s estimated $37 billion annual loss from pollution-related health costs.

- In Pakistan’s Punjab, pollution and smog frequently cause flight delays and school closures, with average life expectancy in Lahore reduced by about five years due to poor air quality.

- These severe outcomes call for joint strategies to monitor and manage air quality across borders, especially during peak pollution periods.

Urban Heat and Climate Vulnerability

- India and Pakistan’s rapidly urbanizing cities face intensifying urban heat due to impervious surfaces that radiate heat. This urban heat effect exacerbates health issues, particularly as many cities lack adequate cooling systems.

- Even as heat waves may not directly influence each other, urban heat islands and their spillover effects are raising temperatures across the region, adding to concerns like glacier melting. Rising urban temperatures also increase energy demand, contributing further to environmental degradation.

- Both nations need collaborative initiatives in urban planning and renewable energy deployment to address the shared consequences of urban heat and mitigate its impact on both urban and rural populations.

Impact of Glacier Melting on Shared Water Resources

- The accelerated melting of glaciers in the Hindu Kush and Karakoram ranges, exacerbated by pollutants like black carbon, is a critical concern for both nations.

- These glaciers are a vital water source for the transboundary Indus River basin, which sustains the agriculture and drinking water needs of 300 million people in India and Pakistan.

- If glacier melt continues unabated, it could drastically reduce river water levels, straining already overburdened groundwater systems and impacting food and water security.

- Joint action to reduce black carbon emissions, monitor glacier health, and manage water resources could be crucial to preserving the region’s water supply and sustaining agricultural productivity.

Sea Level Rise and Coastal Vulnerabilities

- The consequences of climate change extend to rising sea levels, which threaten coastal regions along the Arabian Sea. Both Indian and Pakistani coastal communities face heightened risk from storm surges, cyclonic tides, and saline water intrusion, which endangers drinking water supplies and agricultural viability.

- Low-lying areas, such as the Indus Delta, have already lost a significant portion of coastline, with projections indicating further loss due to rising sea levels.

- This environmental threat necessitates collaboration on coastal resilience strategies, such as disaster preparedness, climate-resilient infrastructure, and sustainable livelihood options for affected communities.

Potential for Improved Relations Through Environmental Cooperation

- While political conflicts and historical tensions have long complicated Indo-Pak relations, the shared threat of climate change offers a unique opportunity for collaboration. Initiatives such as data sharing, joint climate research, and technology exchanges could pave the way for long-term cooperation.

- By working together to address these urgent environmental challenges, both nations could foster improved relations and build a foundation for trust, especially among younger generations less influenced by the legacy of partition.

- Such collaboration could eventually extend beyond climate issues, opening pathways for cooperation in various other fields and fostering regional stability.

| Particulate Matter (PM) |

|

|

PYQ: In the cities of our country, which among the following atmospheric gases are normally considered in calculating the value of the Air Quality Index? (2016) 1) Carbon dioxide 2) Carbon monoxide 3) Nitrogen dioxide 4) Sulphur dioxide 5) Methane Select the correct answer using the code given below: (a) 1, 2 and 3 only (b) 2, 3 and 4 only (c) 1, 4 and 5 only (d) 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 Ans: (b) |