Is the caste Census a useful exercise?

(Source – The Hindu, International Edition – Page No. – 10)

| Topic: GS2 – Governance |

| Context |

| ● The demand for a caste Census has sparked political debates, with proponents advocating for data to ensure proportional representation in government jobs, land, and wealth.

● However, challenges in accurate caste data collection and the flaws in caste-based reservation policies are significant concerns. ● Some scholars critique this approach as impractical and regressive. |

Caste Census: A Political Issue

- The demand for a caste Census has gained momentum, fueled by opposition leaders, NGOs, and even the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

- Proponents argue that a caste Census would provide accurate data on caste populations, which can be used to ensure a proportionate share in government jobs, land, and wealth for each caste.

Historical Background of Caste Census

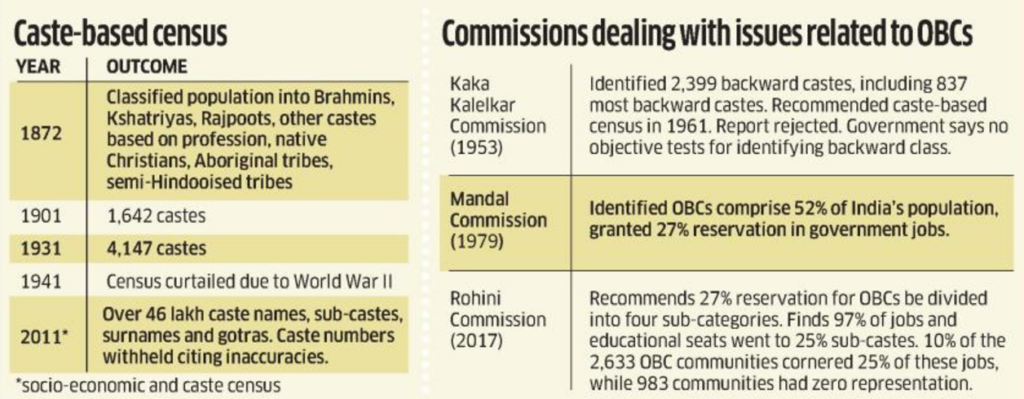

- The caste Census exercise dates back to the late 19th century, with the first detailed caste Census conducted in 1871-72.

- The 1871 Census collected caste data in regions like North-Western Provinces, Central Provinces, Bengal, and Madras, but the classification of castes was arbitrary and superficial.

- The Census of 1931 identified 4,147 castes, but caste groups often reported different identities across regions.

- These issues persisted in later Census exercises, such as the Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) of 2011, which recorded over 46.7 lakh castes/sub-castes with 8.2 crore acknowledged errors.

- The controversy continues, as seen in the Bihar Census of 2022, which sparked debates over the inclusion of ‘hijra’ and ‘kinnar’ as separate categories.

Challenges in Accessing Accurate Data

- Upward Caste Mobility: Caste claims may be influenced by the perceived prestige of certain groups, leading some communities to claim higher positions in the caste hierarchy for social advantages.

- Downward Caste Mobility: Some respondents may claim lower caste status to gain benefits from reservation policies. This trend is primarily a post-independence phenomenon.

- Caste Misclassification: Similar-sounding castes and surnames can lead to confusion and misclassification. For instance, surnames like ‘Dhanak’ and ‘Dhankia’ in Rajasthan are categorized differently as SC and ST, respectively. Misclassification may also arise due to discomfort among enumerators and respondents discussing caste.

The Problem with Proportional Representation in Reservations

- Proportional representation in reservations, though seemingly fair, is impractical and regressive.

- Proportional representation in reservations means that positions are allocated based on the percentage of each reserved group.

- For example, a group with 27% reservation would get every 4th position in a list of vacancies.

- While this seems fair, applying this to individual castes creates problems. Many castes have very few people, making it hard for them to get reserved positions.

- In some cases, it could take hundreds or even thousands of years for a small caste to get a single reserved vacancy.

- This system is flawed and unfair, as it excludes the smallest and least represented groups.

Conclusion

- The article argues that proportional representation based on caste is not only impractical but also regressive.

- It disproportionately excludes the least populous castes from benefiting from reservations.

- The challenges in accurately classifying castes further undermine the feasibility of a caste Census.

| PYQ: Has caste lost its relevance in understanding the multi-cultural Indian Society? Elaborate your answer with illustrations. (150 words/10m) (UPSC CSE (M) GS-1 2020) |

| Practice Question: Discuss the challenges of implementing a caste Census in India, highlighting issues related to caste misclassification and data accuracy. Evaluate the effectiveness and implications of caste-based proportional reservations in India. (250 Words /15 marks) |