29 August 2024 : Indian Express Editorial Analysis

1. A punishing process

(Source: Indian Express; Section: The Ideas Page; Page: 09)

| Topic: GS2– Governance |

| Context: |

|

Introduction: The Principle of Bail Over Jail

- Recent Supreme Court judgments have reinforced the principle that “bail is the rule, and jail is the exception,” even when it comes to stringent laws like the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA) and the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA).

- This stance has significant implications, particularly in high-profile cases such as that of BRS leader K Kavitha, where the court highlighted that undertrial custody should not turn into a form of punishment.

- These judgments mark a shift in the judiciary’s approach, emphasizing the protection of individual liberty against prolonged detention without trial.

Judicial Scrutiny of PMLA and Enforcement Directorate (ED) Practices

- The judiciary has also been critical of the Enforcement Directorate’s (ED) methods under the PMLA, reflecting a growing concern about the potential misuse of the law.

- For instance, a Delhi court criticized the ED for using stringent PMLA provisions to summon private doctors and record their statements, warning that such practices could backfire on the very citizens the law aims to protect.

- Similarly, a Mumbai court reminded the ED of its constitutional obligation to ensure an expedited trial, granting bail to two individuals who had been incarcerated since October 2020.

- These cases underline the need for a careful review of the ED’s functioning and the application of PMLA to prevent the abuse of power.

Historical Context and Political Ramifications

- The PMLA was framed in response to international commitments, such as India’s 1998 signing of the UN Declaration on combating money laundering.

- However, two decades later, the law has become a tool of political contention, with the ED often perceived as targeting opposition parties.

- The Supreme Court’s upcoming review of PMLA provisions, especially in light of the 2022 Madan Lal Choudhary verdict that upheld certain aspects of the law, will be crucial in addressing concerns about the law’s constitutionality and the ED’s perceived bias.

Expansion of ED’s Powers and Its Impact

- Over the years, amendments to the PMLA have significantly expanded the ED’s powers, leading to concerns about overreach. The 2012 amendment broadened the definition of money laundering, while subsequent amendments in 2015 and 2018 tightened bail conditions and allowed for the seizure of assets without an FIR.

- The 2019 amendment further empowered the ED with wide-ranging authority to summon, arrest, and raid individuals, making money laundering a standalone offense.

- While these changes have led to an increase in the number of cases registered and assets attached, the effectiveness of these measures in achieving justice remains debatable, as evidenced by the low conviction rate.

Performance and Challenges of the ED

- Despite the ED’s increased activity under the PMLA, with more cases registered and assets attached than during previous regimes, the agency faces significant challenges.

- The low number of convictions, coupled with the lengthy judicial process, raises questions about the efficacy of the law and the ED’s ability to handle its caseload.

- Moreover, the agency’s limited manpower and resources hinder its ability to conduct thorough and timely investigations, leading to concerns about selective enforcement and the prioritization of cases based on political considerations.

The Broader Implications for Democracy and Rule of Law

- The PMLA’s stringent provisions, such as the lack of requirement for an ECIR to arrest individuals and the admissibility of statements made before the ED, pose serious risks of misuse.

- In a democratic society, the balance between enforcing the law and protecting individual rights is crucial. The Supreme Court’s forthcoming review of the PMLA will be a critical test of whether the law can be reconciled with constitutional principles.

- If the judiciary fails to provide relief, it may fall upon the public and their elected representatives to push for amendments that safeguard democracy and prevent the abuse of power.

| What is Section 45 of the PMLA? |

|

Section 45 of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) speaks about the conditions set for bail. It states that no accused person shall be granted bail unless:

Basically, this section prescribes a rather high bar for granting bail. The negative language in the provision itself shows that bail is not the rule but the exception under PMLA. Twin test of bail under Section 45 of PMLA

Exceptions

Legal precedent for such exceptions

|

| PYQ: Discuss how emerging technologies and globalisation contribute to money laundering. Elaborate measures to tackle the problem of money laundering both at national and international levels. (150 words/10m) (UPSC CSE (M) GS-3 2021) |

| Practice Question: Discuss the implications of the Supreme Court’s emphasis on the principle ‘bail is the rule, jail is the exception’ in the context of special laws like the UAPA and PMLA. How do these judgments reflect on the balance between individual liberties and state powers? (250 words/15 m) |

2. BREAKING A HARMFUL PATTERN

(Source: Indian Express; Section: The Editorial Page; Page: 08)

| Topic: GS2– Social Justice – Vulnerable Sections |

| Context: |

| The article discusses the increasing violence against female caregivers, such as teachers, nurses, and doctors, in India. |

The Role and Challenges of Caregivers in Society

- Caregivers play a crucial role in maintaining the health and well-being of society. Traditionally, caregiving roles are often seen through the lens of gender stereotypes, with expectations that women, in particular, should be nurturing, patient, and self-sacrificing.

- These stereotypes can lead to a lack of respect for the professional boundaries of caregivers, making them more vulnerable to violence and exploitation.

Increasing Violence Against Female Caregivers

- The rise in violence against female caregivers, such as teachers, nurses, social workers, and doctors, can be attributed to a complex mix of social, cultural, economic, and systemic factors.

- Deep-rooted misogyny and sexism contribute significantly, as women in caregiving roles are often targeted simply because of their gender.

- The lack of adequate support systems further exacerbates their vulnerability to aggression from patients, students, and even colleagues.

- The tragic incidents of violence against caregivers, such as the killing of teacher Rajni Bala in Kashmir and the rape and murder of a trainee doctor in Kolkata, highlight the increasing dangers faced by women in these roles.

Changing Nature of Violence in India

- Over the past decade, the nature of violence in India has evolved, becoming more frequent and brutal, particularly against women and children.

- This shift raises questions about the underlying value systems in the country, the effectiveness of educational practices, and the attitudes of those in power.

- The normalization of toxic masculinity in media, the easy availability of pornography, and a culture that prioritizes immediate gratification contribute to a societal environment where violence and aggression are increasingly common.

Understanding the Roots of Violent Behavior

- Violence and deviant behavior do not stem solely from dysfunctional backgrounds or mental illness. Perpetrators of such crimes often come from varied social and economic backgrounds, challenging the stereotype that only those from troubled lives engage in criminal activities.

- The real question lies in understanding the anatomy of a person who preys on others, especially those weaker than themselves.

- Addressing this requires a deeper exploration of how these violent tendencies develop and manifest.

The Need for a Cultural and Educational Revolution

- To combat the rising violence, a revolution in cultural and educational practices is necessary. This change must start at the grassroots level, with communities, families, and schools across both urban and rural India undergoing significant transformation.

- Gender sensitization, challenging harmful stereotypes, teaching emotional management, conflict resolution, and effective communication are essential steps in this process.

- Local leaders and religious figures also have a crucial role in advocating for peace and respect within communities.

Shaping a New Socialization of Boys and Manhood

- A broader societal shift is needed in how boys are socialized and how manhood is defined.

- This involves rethinking the role of religious belief systems, sports culture, family structures, educational institutions, and the economy in shaping attitudes and behaviors.

- Leadership training, along with sensitivity training, is crucial to ensure that those in power prioritize these issues.

- By fostering environments that emphasize empathy, compassion, and respect, we can work towards reducing violence and creating a safer society.

Conclusion: Building a Compassionate Future

- The future of society depends on how we nurture the next generation. Parents, educators, and society as a whole must take an active role in broadcasting meaningful messages that promote empathy, compassion, and critical thinking.

- By doing this collectively, we can help children grow into conscientious adults who contribute positively to the world, ultimately reducing violence and fostering a more just and compassionate society.

| What are the Statistics on Women’s Safety? |

|

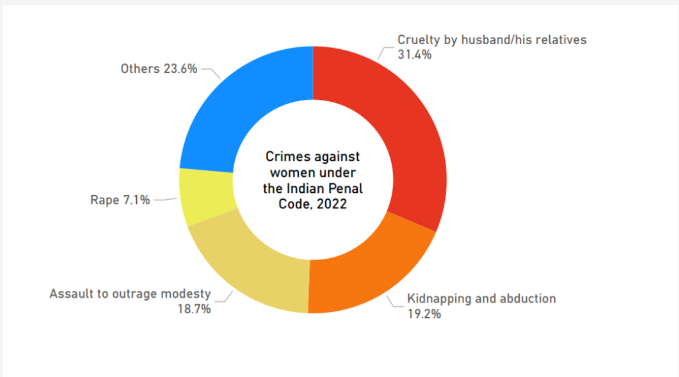

Types of Crimes: The majority of crimes against women were categorized as cruelty by husband or relatives, making up 31.4% of cases.

State-wise Data: Delhi had the highest rate of crimes against women, with a rate of 144.4 per lakh population and 14,247 cases reported in 2022.

|

| PYQ: Is the National Commission for Women able to strategize and tackle the problems that women face at both public and private spheres? Give reasons in support of your answer. (250 words/15m) (UPSC CSE (M) GS-2 2017) |

| Practice Question: Examine the rising incidents of violence against female caregivers in India. How do traditional gender roles and systemic factors contribute to this issue? Suggest measures that can be implemented to protect caregivers and address the root causes of such violence. |