6 July 2024 : The Hindu Editorial Analysis

1. Spiritual orientation, religious practices and courts

(Source – The Hindu, International Edition – Page No. – 6)

| Topic: GS2 – Indian Polity – Judiciary |

| Context |

| The article discusses a controversial Madras High Court ruling allowing the religious practice of angapradakshinam, highlighting debates on religious freedoms, judicial consistency, and constitutional principles in India’s legal landscape. |

Introduction:

- Chief Justice Lathman of Australia in 1943 stated, “What is religion to one is superstition to another,” underscoring the subjective nature of religious beliefs.

- Religion has long been central to human societies, with a notable surge in religiosity and a decline in spirituality currently observed in India.

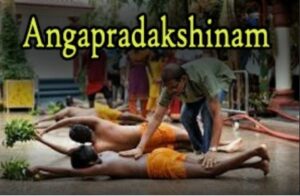

Judicial Order on Angapradakshinam:

- Justice G.R. Swaminathan of the Madras High Court issued a significant and contentious order in P. Navin Kumar (2024), permitting the religious practice of angapradakshinam.

- This practice involves rolling over banana leaves used by devotees of Sri Sadasiva Brahmendral in Tamil Nadu, overturning a previous 2015 order by Justice S. Manikumar.

| Practice of angapradakshinam: |

|

Previous Legal Controversy:

- In 2015, objections were raised citing caste discrimination concerns, alleging that Dalits and non-Brahmins rolled over leftover plantain leaves.

- Justice Manikumar based his decision on a Supreme Court order involving a similar ritual stayed in Karnataka, primarily involving Dalits.

Revival of Debates on Religion and Essential Practices:

- Justice Swaminathan’s order has reignited debates on the definition of religion, determination of essential religious practices, and judicial consistency in such matters.

- He justified his decision by invoking Article 25 (freedom of religion), Article 21 (right to privacy), and Article 19(1)(d) (freedom of movement) of the Indian Constitution, asserting the petitioner’s rights.

Legal and Philosophical Considerations:

- The Indian Constitution subordinates religious freedoms to other fundamental rights and allows state intervention for public order, health, and morality, emphasising ‘essential religious practices.’

- Only a small fraction of cases have successfully claimed protection under ‘essential religious practices,’ prompting critical evaluation of Justice Swaminathan’s recent ruling.

Criticism and Constitutional Challenges:

- Concerns were raised regarding the hygiene and health hazards associated with the practice of angapradakshinam, questioning its compatibility with the right to privacy in a public event.

- Justice Swaminathan defended privacy rights, analogizing spiritual orientation to sexual and gender orientations, arguing for individual expression within legal boundaries.

Supreme Court Precedents and Religious Freedoms:

- The landmark case of Sri Shirur Mutt (1954) established that Article 25 protects outward acts of religious belief, relying on the doctrines of the respective religion to define essential practices.

- However, subsequent interpretations varied, sometimes diverging from religious texts to judicial reasoning, as seen in The Durgah Committee, Ajmer (1961) and other cases.

| The Durgah Committee, Ajmer Case (1961) |

|

Controversial Applications of the ‘Essentiality Test’:

- Instances such as the Gramsabha of Village Battis Shirala (2014) and Mohammed Fasi (1985) demonstrate varied judicial approaches, from specific religious texts to empirical evidence and community practices.

- In Gramsabha of Village Battis Shirala (2014), the court addressed a sect’s claim that capturing and worshipping a live cobra during nagpanchami was an essential religious practice. The court ruled against this, citing lack of specific mention in relevant religious texts.

- In Mohammed Fasi (1985), a Muslim policeman challenged a ban on growing a beard in Kerala. The court rejected the claim, citing lack of mandatory requirement in the Quran.

- The evolving nature of essential religious practices has led to inconsistencies, as illustrated in cases like Acharya Jagdishwarananda Avadhuta (2004) and M. Ismail Faruqui (1995).

| Essentiality Test |

|

Constitutional Supremacy and Religious Governance:

- The Constitution of India is upheld as paramount, guiding the extent of religious freedoms granted, ensuring alignment with constitutional ethos and values.

- Judicial prudence necessitates cautious adjudication on theological matters, emphasising constitutional principles over theological interpretations.

Conclusion:

- Balancing religious freedoms with societal interests and constitutional values remains a critical challenge for Indian judiciary.

- The debate sparked by Justice Swaminathan’s ruling underscores the ongoing evolution and complexity in defining and protecting essential religious practices within a secular constitutional framework.

| Practice Question: Discuss the implications of judicial rulings on religious practices like angapradakshinam in India. How should the judiciary balance religious freedoms with constitutional principles? (150 Words /10 marks) |

Angapradakshinam is a religious practice observed in some Hindu traditions, notably at the Sri Sadasiva Brahmendral temple in Tamil Nadu.

Angapradakshinam is a religious practice observed in some Hindu traditions, notably at the Sri Sadasiva Brahmendral temple in Tamil Nadu.