7 August 2024 : The Hindu Editorial Analysis

1. Powering up to get to the $30-trillion economy point

(Source – The Hindu, International Edition – Page No. – 8)

| Topic: GS3 – Indian Economy |

| Context |

|

Introduction

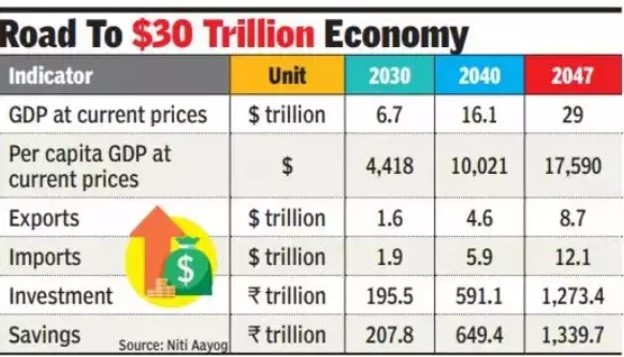

- India’s 7%-plus GDP growth and status as the fastest-growing large economy are frequently cited to predict the 21st century as ‘India’s century.’

- Despite the optimism, India must not assume economic growth is inevitable. Many countries have failed to transition to developed nation status despite promising starts.

- Goal for 2047: For India to become a $30-trillion economy by 2047, it must pursue rapid growth based on liberal economic policies that harness the private sector, despite criticisms of income inequality.

Economic Growth and Poverty Alleviation

- Impact of Economic Growth: Economic growth is crucial for poverty alleviation. Between 1991 and 2011, liberalisation reduced India’s poverty rate from 50% to 20%, lifting 35 crore people out of poverty.

- Income Inequality Debate: While inequality may have increased post-1991, more Indians are better off, especially those at the bottom of the pyramid. Wealth creation is essential for entrepreneurship and improves living standards for all.

Challenges and Opportunities

- Past Economic Reforms: The gains from the 1990s reforms have been realised. The 2000-2010 IT boom created an affluent middle class, but 46% of the labour force remains in low-productivity agriculture, contributing just 18% of GDP.

- Female Labor Force Participation Rate (FLFPR): India’s FLFPR is 37%, much lower than in China, Vietnam, and Japan (60%-70%). Increasing FLFPR is essential for unlocking India’s working-age population potential.

Unlocking Economic Potential

- Learning from ‘Asian Tigers’: South Korea, Taiwan, Japan, and Vietnam achieved rapid growth through low-skilled, employment-intensive manufacturing and export orientation. India must follow a similar path.

- Exports and Openness: From 1990 to 2013, India’s exports as a percentage of GDP grew from 7% to 25%. To capitalise on global opportunities, India must avoid protectionist tariffs that could hinder competitiveness.

Avoiding the Middle-Income Trap

- Risks of Protectionism: Import tariffs risk creating inefficient manufacturers and inflating production costs, potentially leading to a middle-income trap. India must transition from low-end to high-tech sectors.

- Manufacturing and Value Chain: India’s inability to leverage surplus labour in low-end manufacturing is a challenge. Developing ecosystems for low-tech manufacturing is vital for moving up the value chain.

- Perception of Manufacturing Jobs: Campaigns that depict factories as sweatshops can be detrimental. Low-wage jobs are crucial for those with limited alternatives outside agriculture.

- Market-Led Economy: Avoiding the middle-income trap requires a market-led economy that supports private enterprise without excessive government interference.

Infrastructure and Industrial Clusters

- Cluster-Led Industrial Development: India must build industrial clusters with modern infrastructure and ancillary services, similar to China and Vietnam, to attract employers and workers.

- Addressing Cost Disabilities: Indian states face challenges such as high costs for power, logistics, and compliance burdens. Relaxing regulations in designated areas can create a favourable environment for manufacturing.

- Focus on Low-Skilled Manufacturing: The government should prioritise low-skilled manufacturing in sectors like electronics assembly and apparel to employ large numbers of people.

- Urbanization and Migration: Increasing interstate migration and urbanisation, along with a decline in agriculture’s share of employment, will indicate progress toward becoming a $30-trillion economy by 2047.

Conclusion

- India’s challenges present exciting opportunities.

- Addressing barriers to growth will pave the way for prosperity and fulfil India’s destiny as a Vishwaguru.

- India must adopt ambitious, forward-thinking policies to achieve its economic goals and capitalise on its potential.

| Practice Question: Discuss the challenges and strategies for India to transition from a middle-income to a high-income economy by 2047. In your answer, highlight the role of liberal economic policies, manufacturing, and labour force participation. (250 Words /15 marks) |

2. Counting the ‘poor’ having nutritional deficiency

(Source – The Hindu, International Edition – Page No. – 9)

| Topic: GS2 – Social Justice – Health |

| Context |

|

Introduction

- The National Sample Survey Office released a report based on the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) for 2022-23, along with unit-level data on household consumption expenditure (HCE) now available to the public.

- The HCES collected data on quantities of food items consumed by households and the total value of consumption for both food and non-food items.

- The analysis converts the quantities of consumed food items into their total calorific value and compares it with average per capita daily calorie requirements.

Defining Poverty and Measuring Nutrition

- Defining the ‘Poor’: Various government committees, such as Lakdawala, Tendulkar, and Rangarajan, have defined the poor as persons below the poverty line (PL), a monetary threshold based on household monthly per capita consumer expenditure (MPCE).

- Calorie Norms and Poverty Line: The Lakdawala Committee anchored the PL and the poverty line basket (PLB) to calorie norms: 2,400 kcal per capita per day for rural areas and 2,100 kcal per capita per day for urban areas. The Tendulkar Committee did not use a calorie norm, while the Rangarajan Committee considered adequate nourishment, clothing, house rent, conveyance, education, and other non-food expenses.

Methodology

- Calorie Requirement Calculation: The analysis derives the average daily per capita calorie requirement (PCCR) for a healthy life using recommended energy requirements for different age-sex-activity categories from the 2020 ICMR-National Institute of Nutrition report.

- Data Arrangement: Individuals are arranged into 20 fractile classes of MPCE (poorest to richest), each comprising 5% of the population. Estimates of average per capita per day calorie intake (PCCI) and average MPCE for food and non-food items are derived for each class based on HCES 2022-23 data.

Minimum Expenditure for Healthy Life

- Average Per Capita Expenditure: The average per capita expenditure on food needed for a healthy life is considered the minimum amount a household must spend. This is combined with the average MPCE on non-food items for the poorest 5% to derive the total MPCE threshold necessary for adequate nourishment and basic non-food expenditure.

- State-Specific Thresholds: The all-India total MPCE threshold is adjusted for price differentials across States/UTs using general Consumer Price Index numbers, deriving State/UT-specific total MPCE thresholds.

Proportion of ‘Poor’ and Nutritional Deficiency

- Proportion of ‘Poor’: The proportion of ‘poor’/deprived is calculated based on the MPCE thresholds. The proportion for the country is the weighted average of State/UT proportions, using projected populations as weights.

- Calorie Intake Shortfall: The Per Capita Calorie Requirement is estimated at 2,172 kcal for rural India and 2,135 kcal for urban India. The estimated proportion of ‘poor’ is 17.1% for rural areas and 14% for urban areas.

Impact of Non-Food Expenditure and Nutritional Programs

- Impact of Broader Measurement: Considering the non-food expenditure of the poorest 10% instead of the poorest 5% raises the threshold total MPCE to ₹2,395 for rural areas and ₹3,416 for urban areas, increasing the proportion of deprived to 23.2% for rural India and 19.4% for urban India.

- Calorie Intake Deficiency: The average PCCI of the poorest 5% and the next 5% in rural India is 1,564 kcal and 1,764 kcal, respectively. In urban India, it is 1,607 kcal and 1,773 kcal, both significantly lower than the PCCR.

Conclusion and Recommendations

- The government has various welfare programs aimed at uplifting the poor and improving health conditions.

- Targeted nutritional schemes for the poorest could significantly enhance their nourishment levels, promoting a healthier life.

| Practice Question: Critically analyse the methodology and findings of the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2022-23 in assessing poverty and nutritional adequacy in India. How can targeted nutritional schemes improve health outcomes for the poorest sections of society? (250 Words /15 marks) |