8 November 2024 : The Hindu Editorial Analysis

1. All eyes on Baku and the climate finance goal

(Source – The Hindu, International Edition – Page No. – 8)

| Topic: GS2 – International Relations – Agreements involving India or affecting India’s interests. |

| Context |

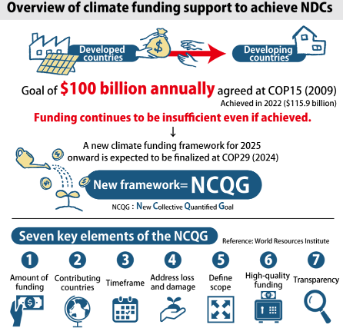

| The New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG), set to be finalised at COP29 in Baku, will define future climate finance commitments, with a focus on addressing the unique needs of developing countries.Key issues include equitable financial contributions, adaptation funding, and the scope of responsibility for developed nations.This evolving climate finance framework aims to restore trust between developed and developing countries. |

Introduction to the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) at COP29

- COP29, held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from November 11-22, 2024, is focused on climate finance, with the NCQG expected to determine its success.

- Article 9 of the Paris Agreement mandates that climate finance must address the needs and priorities of developing countries, which will be central to NCQG’s framework.

Unresolved Issues in NCQG Negotiations

- Diverse interests have led to disagreements over the NCQG’s structure, scope, funding scale, timeframes, and sources.

- Developing countries emphasise that the financial responsibility should not shift unfairly onto them, focusing on equity, adaptation, and public finance with clear, predictable targets.

- In contrast, developed countries advocate broadening the contributor base, emphasising innovation and flexible finance structures.

Challenges in Achieving Climate Finance Commitments

- The $100 billion annual climate finance pledge from 2009, extended to 2025, was only met in 2022, causing distrust due to previous missed deadlines.

- The Standing Committee on Finance estimates that climate action requires between $5.036 trillion and $6.876 trillion, far beyond the current $100 billion target.

- The OECD reported that $115.9 billion was mobilized in 2022, but adaptation remains underfunded, with an overreliance on loans that increase debt for vulnerable countries.

Need for Grants-Based Public Finance

- Grants should form the core of climate finance, with concessional loans supplementing them, while private investments are better suited to clean energy rather than adaptation projects.

- Adaptation projects, including infrastructure resilience and disaster management, remain underfunded due to a financial bias toward mitigation.

- Developing countries face challenges accessing funds from entities like the Green Climate Fund, further hindering their adaptation efforts.

Controversy over Expanding the Contributor Base

- Developed countries, particularly Canada and Switzerland, propose expanding contributors based on emissions and income criteria, which would include countries like China, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE.

- Developing countries view this move as undermining equity and the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities,” potentially stalling COP29 negotiations.

Shift in Developed Countries’ Narrative

- Developed countries are shifting focus to “low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development,” seen as a way to dilute their obligations under the Paris Agreement.

- This shift could violate the principle of pacta sunt servanda, which upholds the integrity of treaties, by weakening Article 9 of the Paris Agreement.

Operational Definition of Climate Finance

- The SCF defines climate finance as funding aimed at reducing emissions, increasing resilience, and aligning with national climate goals, but the lack of reference to additionality introduces ambiguity.

- Private investments, though counted in NCQG, often lack the public accountability necessary for adaptation, risking diluted accountability for developed countries.

Additional Support Required for Developing Countries

- In addition to finance, developing countries need technology transfer and capacity building, which are hindered by procedural barriers within multilateral mechanisms.

Conclusion

- The success of NCQG at COP29 depends on whether it restores trust between developed and developing countries by addressing historical responsibilities and the specific needs of developing nations.

- The outcome will determine if the global climate finance mechanism delivers equitable solutions or falls short, with the potential to widen the divide if multilateral commitments are unmet.

| Practice Question: Discuss the significance of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) for climate finance at COP29 and examine the challenges in achieving an equitable financial framework for developing nations. (150 Words /10 marks) |

2. India, Pakistan and modifying the Indus Waters Treaty

(Source – The Hindu, International Edition – Page No. – 8)

| Topic: GS2 – International Relations – Bilateral Relations |

| Context |

| India formally served notice to review and modify the Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) on August 30, 2024, citing Article XII (3), which allows modifications in the treaty with mutual agreement.The notice reflects India’s concerns over increasing domestic water demands, demographic changes, agricultural needs, and the requirement to meet clean energy goals.India also raised concerns over cross-border terrorism in Jammu and Kashmir, which it argues impedes the full utilisation of its water rights under the treaty. |

Divergent Interpretations of the Treaty

- India, as the upper riparian state, views the treaty as a tool for optimal water utilisation, while Pakistan, as the lower riparian state, sees it as guaranteeing uninterrupted water flow.

- This difference in interpretation has led to disputes and legal proceedings, including the 2013 Kishenganga arbitral award, where India’s right to build hydroelectric projects was upheld with conditions on maintaining minimum water flow.

Hydropower Projects and Minimum Flow Requirement

- India has been developing hydropower projects on western rivers, with 33 projects either under construction or in the planning phase.

- While the IWT allows India to use these rivers for hydropower, it mandates the maintenance of minimum flow to ensure downstream availability for Pakistan.

Challenges in Water Resource Management

- The IWT separates the Indus Basin into eastern and western waters, with India having rights to eastern rivers (Ravi, Sutlej, Beas) and Pakistan to western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, Chenab).

- The treaty’s structure limits integrated water resources management and cooperation between India and Pakistan, complicating efforts to optimise basin-wide water management.

Legal Obligations and the ‘No Harm’ Rule

- Although the IWT lacks a specific provision for the “no harm” rule, this principle is part of customary international law, requiring each country to prevent significant harm when developing projects with potential cross-boundary effects.

- According to the International Court of Justice’s ruling in the 2010 Pulp Mills case both countries must conduct environmental impact assessments (EIAs) for projects with transboundary impact.

Equitable and Reasonable Utilisation (ERU)

- The 1997 UN Watercourses Convention outlines the ERU principle in Articles 5 and 6, which could guide India and Pakistan in managing unforeseen climate change impacts like glacial melt.

- Climate change-related factors, such as a 30%-40% reduction in water flow from glacial depletion, underscore the need for ERU to ensure fair water distribution and sustainable resource management.

Potential for Joint Projects and Cooperation

- IWT also suggests that India and Pakistan could cooperate on joint engineering projects along the Indus to mitigate water variability due to climate change.

- Joint projects could help both countries manage water variability and improve resilience, but this requires significant trust and cooperation.

Suggestions for Moving Forward

- Given the trust deficit, full renegotiation of the IWT may be challenging.

- A feasible approach could involve formal negotiation under the IWT framework to reach a memorandum of understanding for handling emerging issues, while retaining the treaty as a basis for basin development and cooperation.

| PYQ: Present an account of the Indus Water Treaty and examine its ecological, economic and political implications in the context of changing bilateral relations. (200 words/12.5m) (UPSC CSE (M) GS-1 2016) |

| Practice Question: Examine the implications of India’s recent move to seek a review of the Indus Waters Treaty in light of its domestic water needs, security concerns, and climate change impacts. (150 Words /10 marks) |