REORGANISATION OF STATES

- Evolution of Reorganization of States (PYQ 2022)

- Linguistic Reorganisation of States

- Impacts of Linguistic Reorganisation of States (PYQ 2016)

- Creation of New States (Post-1956)

- Impact of State Reorganisation

- Challenges in State Reorganisation

- Judicial and Constitutional Aspects

- Current Issues and Future Prospects

- Is Formation of New States In Recent Times Beneficial? (PYQ 2018)

- Related FAQs of REORGANISATION OF STATES

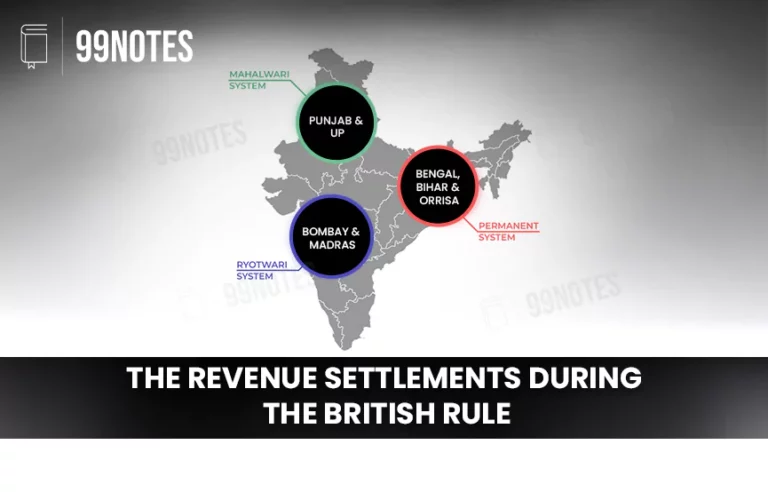

British-era administrative divisions

British-era administrative divisions

During British rule, the Indian subcontinent was divided into British provinces and princely states. The British provinces were directly administered by the British government, while the princely states were ruled by local monarchs under British suzerainty. These divisions were primarily based on administrative convenience, historical conquests, and political expediency rather than cultural or linguistic considerations. Provinces like the Bombay Presidency, Madras Presidency, and Bengal Presidency comprised diverse linguistic and ethnic groups, leading to administrative challenges and regional discontent.

Evolution of Reorganization of States (PYQ 2022)

The political and administrative reorganization of Indian states and territories has been a continuous process, shaped by historical, political, and socio-cultural factors. Beginning with British colonial policies in the mid-19th century, this process continued post-independence to accommodate linguistic, ethnic, and regional aspirations.

- Colonial Reorganization (1858–1947): The British reorganized territories for administrative convenience, such as the formation of Bengal Presidency and the partition of Bengal (1905), which was reversed in 1911 due to public opposition.

- Post-Independence Reorganization (1947–1956): The political map of India was redrawn after independence, merging over 500 princely states into the Indian Union. The States Reorganisation Act (1956) created states based on linguistic identity, such as Andhra Pradesh (1953).

- Creation of New States (1960–2000): Growing demands for regional autonomy led to the creation of Maharashtra and Gujarat (1960), Punjab and Haryana (1966), and smaller states like Nagaland (1963), Meghalaya (1972), and Sikkim’s merger (1975).

- Formation of Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Uttarakhand (2000): The reorganization was driven by demands for better governance and regional development, resulting in the creation of three new states carved from Madhya Pradesh, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh.

- Recent Reorganization (2014): Telangana was carved out of Andhra Pradesh to address regional disparities and political demands, becoming India’s 29th state.

- Union Territory Reorganization (2019): Jammu & Kashmir was reorganized into two union territories—Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh—through the abrogation of Article 370 to integrate it more closely with the Indian Union.

- Ongoing Demands: Current demands for separate states like Gorkhaland (West Bengal), Vidarbha (Maharashtra), and Bundelkhand (Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh) reflect the ongoing nature of political and administrative reorganization.

The reorganization of states and territories in India reflects the country’s adaptive political framework, balancing regional aspirations with national unity. This continuous process has strengthened democratic governance and regional development while maintaining India’s territorial integrity.

Challenges at the time of independence

At the time of independence, India faced the mammoth challenge of integrating over 500 princely states and reorganising British provinces into a cohesive national framework. The task was further complicated by the country’s vast linguistic and cultural diversity, which raised crucial questions about national unity and regional identity.

- Many linguistic communities such as Telugu, Kannada, Marathi, and Punjabi speakers began demanding separate states where their language would be the medium of governance and education.

- Political leaders initially opposed linguistic reorganisation due to fears of encouraging secessionist tendencies and weakening national unity.

- However, ignoring these demands risked alienating significant sections of the population and undermining democratic legitimacy.

- The turning point came in 1953, when Potti Sriramulu died after a hunger strike demanding a separate state for Telugu speakers, leading to the formation of Andhra state.

| Potti Sriramulu and the Birth of Andhra State |

|

After independence, the demand for a separate state for Telugu-speaking people gained momentum, as they felt culturally and linguistically distinct from the Madras Presidency under which they were administered. Potti Sriramulu, a Gandhian freedom fighter, emerged as a key figure in this movement. In 1952, he undertook a hunger strike demanding the creation of a separate Andhra state for Telugu speakers. Despite public support and growing pressure, the central government remained unresponsive. After fasting for 56 days, Sriramulu passed away on 15 December 1952, sparking widespread protests and unrest across Telugu-speaking regions. His death became a turning point in India’s post-independence political history. The intensity of public emotion and agitation forced the government to act swiftly. Within a few weeks, the Andhra state was formed on 1 October 1953, carved out of the Madras Presidency, with Kurnool as its capital. Potti Sriramulu’s sacrifice highlighted the power of non-violent protest and the strength of regional identity, setting the stage for the linguistic reorganisation of states across India. |

- In response, the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC) was set up in 1953, which recommended the creation of states largely on linguistic lines, culminating in the States Reorganisation Act of 1956.

This historical development reflected the Indian state’s effort to strike a delicate balance between national integration and regional aspirations, ensuring unity while respecting the country’s cultural and linguistic diversity.

| Constituent Assembly Debates |

|

The issue of state reorganisation was intensely debated in the Constituent Assembly, with members divided over whether to form states on linguistic or administrative and economic grounds. Senior leaders like Sardar Patel and Ambedkar opposed immediate linguistic reorganisation, fearing it might fuel regionalism and threaten national unity. However, many leaders from the south and west argued that linguistic states would ensure better governance, identity recognition, and democratic participation. To examine the issue, the Dhar Commission (1948) was formed, which advised against linguistic reorganisation for the time being. Despite this, growing popular pressure, especially in Madras and Bombay, kept the demand alive. Though the Constitution allowed for flexible boundaries under Articles 3 and 4, it avoided committing to linguistic reorganisation at that stage. Ultimately, the debates laid the foundation for the formation of the States Reorganisation Commission in 1953, leading to the creation of linguistic states in 1956. The Assembly’s discussions reflected the need to balance national unity with regional aspirations, a key feature of India’s evolving federalism. |

Linguistic Reorganisation of States

The linguistic reorganisation of states was a landmark development in post-independence India that aimed to redraw internal boundaries to better reflect the linguistic and cultural identities of the Indian population. This process was driven by popular movements, administrative necessity, and the evolving vision of Indian federalism.

Role of the States Reorganisation Commission (1953): In response to growing demands for linguistic states, especially after the creation of Andhra in 1953, the Government of India set up the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC) in December 1953. The commission, chaired by Fazl Ali with members K.M. Panikkar and H.N. Kunzru, was tasked with examining the entire question of the reorganisation of states and suggesting a rational basis for re-drawing boundaries.

Role of the States Reorganisation Commission (1953): In response to growing demands for linguistic states, especially after the creation of Andhra in 1953, the Government of India set up the States Reorganisation Commission (SRC) in December 1953. The commission, chaired by Fazl Ali with members K.M. Panikkar and H.N. Kunzru, was tasked with examining the entire question of the reorganisation of states and suggesting a rational basis for re-drawing boundaries.

The SRC received thousands of memoranda and toured the country extensively. While it acknowledged the importance of language as a basis for statehood, it also emphasised administrative convenience, economic viability, and the need to strengthen national unity. It recommended the creation of 16 states and 3 centrally administered territories. Potti Sriramulu’s death and creation of Andhra Pradesh (1953): The immediate trigger for linguistic reorganisation was the martyrdom of Potti Sriramulu, a Gandhian and freedom fighter, who fasted unto death demanding a separate state for Telugu-speaking people. His death in December 1952 led to massive public unrest and ultimately forced the government to create the state of Andhra (later Andhra Pradesh) in October 1953, carved out of the Madras Presidency. This event demonstrated the intensity of linguistic sentiments and set a precedent for similar demands in other regions.

Potti Sriramulu’s death and creation of Andhra Pradesh (1953): The immediate trigger for linguistic reorganisation was the martyrdom of Potti Sriramulu, a Gandhian and freedom fighter, who fasted unto death demanding a separate state for Telugu-speaking people. His death in December 1952 led to massive public unrest and ultimately forced the government to create the state of Andhra (later Andhra Pradesh) in October 1953, carved out of the Madras Presidency. This event demonstrated the intensity of linguistic sentiments and set a precedent for similar demands in other regions.- Recommendations and implementation of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956: Based on the SRC’s recommendations, the Government of India passed the States Reorganisation Act in 1956. The Act came into effect on 1st November 1956 and reorganised the Indian Union largely along linguistic lines.

- Key changes included:

- Formation of linguistic states like Kerala (for Malayalam), Karnataka (for Kannada), and Maharashtra and Gujarat (separately later in 1960).

- Merging of princely states and former provinces to create more cohesive administrative units.

- Creation of Union Territories like Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, and Andaman & Nicobar Islands.

The linguistic reorganisation of states was a bold and pragmatic response to India’s diversity. It balanced the aspirations of linguistic communities with the need to maintain national unity and administrative coherence.

Impacts of Linguistic Reorganisation of States (PYQ 2016)

The formation of linguistic states in India, starting with Andhra Pradesh (1953) and the States Reorganisation Act (1956), aimed to address regional aspirations and improve governance while maintaining national unity, but it also raised concerns about regionalism and political fragmentation.

Positive Impact

- Political Stability: Linguistic reorganization reduced regional discontent and ensured political stability by creating cohesive political units.

- Administrative Efficiency: It improved administrative efficiency by enhancing communication and governance within states.

- Promotion of Regional Identity: Recognition of linguistic diversity promoted cultural pride and reduced alienation among different communities.

- Reduced Secessionist Tendencies: Accommodating linguistic aspirations helped reduce secessionist tendencies and strengthened the federal structure.

- Grassroots Political Participation: It empowered regional political parties and increased grassroots political participation, reinforcing democratic values.

Criticism

- Rise of Sub-Nationalism: The rise of sub-nationalism has sometimes weakened national identity by strengthening regional loyalties.

- Political Fragmentation: Political fragmentation has emerged as regional parties often prioritize local issues over national interests.

- Inter-State Disputes: Linguistic boundaries have fueled inter-state disputes over resources and administrative control.

- Economic Imbalance: Economic imbalance among states has increased due to unequal development patterns.

The formation of linguistic states enhanced political stability, administrative efficiency, and cultural identity, but it also led to challenges like sub-nationalism, political fragmentation, and inter-state disputes, requiring a balanced approach to maintain national unity.

Creation of New States (Post-1956)

After the major linguistic reorganisation of states in 1956, demands for new states continued to emerge, driven by linguistic, ethnic, cultural, and regional aspirations. These developments reflect the evolving nature of Indian federalism and the state’s capacity to accommodate diversity through constitutional means.

- Formation of Gujarat and Maharashtra (1960): The bilingual state of Bombay, created in 1956, comprised both Marathi and Gujarati-speaking regions. However, linguistic tensions persisted, with both groups seeking separate statehood. The situation escalated into widespread protests led by movements like Samyukta Maharashtra Samiti. As a result, the Bombay Reorganisation Act was passed, and on 1 May 1960, the state was bifurcated into Maharashtra (Marathi-speaking) and Gujarat (Gujarati-speaking).

- Statehood movements in Northeast India: The Northeast region, with its ethnic and cultural diversity, witnessed several movements demanding separate statehood to preserve unique identities.

- Nagaland became the 16th state of India in 1963 following the Naga peace accord.

- Meghalaya was carved out of Assam in 1972 as a separate state for Khasi, Garo, and Jaintia tribes.

- Manipur and Tripura, former princely states and Union Territories post-independence, were granted full statehood in 1972 to recognise their distinct identity and political aspirations.

These moves were aimed at addressing insurgency, ethnic unrest, and promoting regional development in a sensitive border region.

- Formation of Punjab, Haryana, and Himachal Pradesh (1966): Demand for a Punjabi-speaking state gained momentum after independence. The Punjab Reorganisation Act, 1966 led to the creation of:

- Punjab (Punjabi-speaking, with Sikh-majority areas),

- Haryana (Hindi-speaking region), and

- Himachal Pradesh was given Union Territory status and later became a full-fledged state in 1971.

This reorganisation was based on both linguistic and religious considerations and played a key role in addressing regional grievances.

Sikkim’s integration into India (1975): Sikkim, a Himalayan kingdom, became an Indian protectorate in 1950. However, growing political instability and demand for democratic reforms led to a 1975 referendum in which the majority of Sikkimese voted for integration with India. Through a constitutional amendment (36th Amendment Act, 1975), Sikkim became the 22nd state of India.

Sikkim’s integration into India (1975): Sikkim, a Himalayan kingdom, became an Indian protectorate in 1950. However, growing political instability and demand for democratic reforms led to a 1975 referendum in which the majority of Sikkimese voted for integration with India. Through a constitutional amendment (36th Amendment Act, 1975), Sikkim became the 22nd state of India.- Formation of Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, and Jharkhand (2000): In 2000, the Indian government responded to long-standing regional demands for autonomy and better governance by creating three new states:

- Chhattisgarh was carved out of Madhya Pradesh,

Uttarakhand (initially named Uttaranchal) from Uttar Pradesh,

Uttarakhand (initially named Uttaranchal) from Uttar Pradesh,- Jharkhand from Bihar.

These states were formed largely due to regional disparities, tribal identity movements, and the demand for more focused development in backward areas.

- Creation of Telangana (2014): After decades of agitation over issues of neglect and regional disparity, Telangana was carved out of Andhra Pradesh on 2 June 2014. The movement was rooted in cultural identity, economic concerns, and demands for self-governance. It became the 29th state of India and marked a significant example of peaceful and democratic state creation.

The post-1956 creation of new states highlights the flexibility of the Indian Constitution to accommodate diverse aspirations, strengthen federalism, and promote inclusive development =[while maintaining national unity.

| Annexation of Goa and the integration of Sikkim |

|

Goa (1961): Even after India’s independence in 1947, Goa, Daman, and Diu remained under Portuguese rule. Despite India’s diplomatic efforts, Portugal refused to cede control. Growing Goan nationalist movements and Portuguese repression led India to launch Operation Vijay in December 1961. Within 36 hours, Goa was liberated, ending over 450 years of Portuguese rule. Goa became a Union Territory, and in 1987, it attained statehood. This marked India’s assertive stance against colonial remnants. Sikkim (1975): Sikkim was an Indian protectorate post-1947, with the Chogyal (king) retaining internal control. Political unrest in the 1970s, dissatisfaction with the monarchy, and rising demand for democracy led to protests. A referendum in 1975, where over 97% voted for merger, led to Sikkim’s peaceful integration as India’s 22nd state. The move strengthened India’s strategic Himalayan presence and was a model of democratic transition respecting local aspirations. |

Impact of State Reorganisation

The reorganisation of states in India has had far-reaching political, social, and economic consequences. While it began as a response to linguistic and cultural aspirations, over time, it has played a vital role in shaping the structure and functioning of Indian democracy and federalism.

- Strengthening of Federalism and Political Stability: State reorganisation strengthened Indian federalism by accommodating regional and linguistic aspirations through constitutional means. This helped reduce secessionist tendencies and ensured political stability within a democratic framework.

- Rise of Regional Parties and Identity Politics: The creation of linguistic states led to the emergence of strong regional parties like DMK, Shiv Sena, and TDP. While this enhanced democratic representation, it also fueled identity-based politics and regionalism.

- Socio-Economic Development: State reorganisation allowed for more localized governance, leading to better developmental outcomes. States like Chhattisgarh and Uttarakhand witnessed improved resource management and infrastructure development.

- Administrative Efficiency: Smaller and linguistically homogeneous states improved administrative efficiency and communication. Governance became more responsive to local needs, enhancing policy implementation.

- Political Fragmentation: The rise of regional parties sometimes weakened national political stability by creating complex coalition governments. Regional demands occasionally influenced national policy-making disproportionately.

- Inter-State Disputes: Linguistic reorganisation led to disputes over resources, borders, and political influence. Examples include the Cauvery water dispute between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

- Cultural Preservation and Pride: Linguistic states promoted regional languages, traditions, and cultures, enhancing cultural pride and diversity. This contributed to emotional integration with the Indian identity.

- Economic Imbalance: While some states benefited from focused governance, others lagged in development, leading to regional disparities. Uneven resource allocation has contributed to economic inequality across states.

However, the process also exposed and, in some cases, deepened regional disparities. Some states progressed rapidly due to better infrastructure and governance, while others lagged behind, especially those formed from economically backward regions. This uneven development continues to pose challenges for inclusive growth and balanced regional planning.

Challenges in State Reorganisation

While the reorganisation of states in India has largely been a peaceful and constitutional process, it has not been without challenges and controversies. The continued demand for new states, often based on linguistic, ethnic, or cultural identities, raises complex questions about administrative efficiency, national unity, and internal security.

1. Demand for separate statehood: Several regions across India continue to demand separate statehood, citing issues of neglect, cultural identity, and poor governance.

1. Demand for separate statehood: Several regions across India continue to demand separate statehood, citing issues of neglect, cultural identity, and poor governance.

- The Gorkhaland movement in West Bengal seeks a separate state for the Nepali-speaking Gorkha population, centered around the Darjeeling hills. Despite periodic agreements, the demand remains unresolved.

- The Bodoland movement in Assam calls for a separate state for the Bodo tribal population. While the creation of Bodoland Territorial Region (BTR) under peace accords has granted autonomy, some groups still push for full statehood.

Such demands, if not addressed with sensitivity, can lead to political unrest and prolonged agitation.

2. Impact on national unity and internal security: Frequent statehood demands and identity-based movements pose a challenge to national integration and internal stability. In some cases, such movements have turned violent, impacting law and order and causing prolonged disruptions.

The government must balance regional aspirations with the need to maintain national unity. The fear is that unchecked proliferation of states could lead to administrative fragmentation and weaken the authority of the Union.

3. Language and ethnic-based conflicts: Language and ethnicity continue to be sensitive issues in India’s diverse society.

3. Language and ethnic-based conflicts: Language and ethnicity continue to be sensitive issues in India’s diverse society.

- Conflicts have arisen over official language status, as seen in the anti-Hindi agitations in Tamil Nadu or demands for inclusion of certain languages in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution.

- Ethnic tensions, especially in the Northeast, have led to violent insurgencies, such as those involving Naga, Mizo, and Bodo groups, often linked to demands for autonomy or independence. These issues require careful handling through dialogue, decentralisation, and inclusive

While state reorganisation has helped manage diversity and promote regional development, the associated challenges must be addressed through cooperative federalism, transparent governance, and responsive institutions to ensure both unity and diversity are preserved in the Indian polity.

Judicial and Constitutional Aspects

The reorganisation of states in India is deeply rooted in the constitutional framework, with the judiciary playing a vital role in interpreting and upholding the provisions that govern the alteration of state boundaries and creation of new states. The balance between parliamentary authority and federal principles is maintained through constitutional provisions and judicial oversight.

Article 3 of the Indian Constitution: Article 3 empowers the Parliament of India to form new states, alter the boundaries or names of existing states, and unite or divide states. The key features of Article 3 are:

- Parliament can make these changes by law.

- The President must first refer the bill to the concerned state legislature for its views. However, the legislature’s opinion is not binding on Parliament.

- The central government, therefore, has primary authority in matters of territorial reorganisation.

This provision reflects the unitary bias of the Indian Constitution, enabling flexibility in managing the dynamic needs of a diverse and evolving nation. The broad powers given to Parliament have ensured that reorganisation occurs through a legal and constitutional process rather than through coercion or conflict.

Role of the Supreme Court: The Supreme Court of India has played an important role in adjudicating legal disputes arising from state reorganisation. While the judiciary generally upholds the supremacy of Parliament under Article 3, it also ensures that reorganisation laws adhere to constitutional principles such as federalism, equality, and justice.

Notable judicial interventions include:

- Berubari Union case (1960): The Court clarified that while the reorganisation of states falls under Article 3, the cession of territory to a foreign country requires a constitutional amendment under Article 368.

- Babulal Parate v. State of Bombay (1960): The Court upheld Parliament’s authority to create new states and rejected the argument that reorganisation based on language violates the right to equality.

- Re: Presidential Reference on Punjab Termination of Agreements Act (2004): The Supreme Court examined issues related to inter-state river water disputes following reorganisation, reinforcing its role in maintaining legal balance between states.

In addition, the Court has mediated inter-state disputes arising from reorganisation, such as those related to river waters, boundary demarcation, and division of assets and liabilities (e.g., between Andhra Pradesh and Telangana).

Current Issues and Future Prospects

Even after decades of territorial restructuring, the question of state reorganisation remains a dynamic and evolving issue in Indian politics and governance. Demands for new states continue to emerge, raising important debates around federalism, administrative efficiency, and the future structure of the Indian Union.

1. Continuing demands for new states: There are persistent demands from various regions for the creation of new states based on perceived neglect, regional imbalance, and cultural or administrative identity:

- Vidarbha (eastern Maharashtra) demands statehood due to underdevelopment and lack of resource allocation.

Bundelkhand, spanning parts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, cites backwardness and poor

Bundelkhand, spanning parts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, cites backwardness and poor- Ladakh has seen renewed calls for statehood and constitutional safeguards under the Sixth Schedule to protect its unique demographic and cultural identity.

2. Implications for federalism, governance, and political stability: The creation of new states has significant implications:

- On the positive side, smaller states can bring governance closer to the people, allow for better regional planning, and address local grievances more effectively.

- However, frequent demands for reorganisation may lead to administrative fragmentation, inter-state disputes, and strain on Centre-State relations, especially if political considerations overshadow genuine developmental needs.

- The Centre’s handling of such demands affects political stability, particularly in sensitive regions like the Northeast or border areas, where identity politics and security concerns are intertwined.

3. Debate over smaller vs larger states for better governance: There is an ongoing policy and academic debate on whether smaller states are more efficient in governance compared to larger ones:

- Proponents of smaller states argue that they are easier to administer, more responsive to local needs, and promote balanced development (e.g., Chhattisgarh and Uttarakhand have shown governance improvements post-creation).

- Opponents argue that smaller states may lack financial resources, face infrastructural deficits, and may be more susceptible to political instability or Centre-dependence.

- A case-by-case approach is often seen as more pragmatic, taking into account economic viability, cultural cohesion, and administrative preparedness.

Is Formation of New States In Recent Times Beneficial? (PYQ 2018)

The formation of new states in India, such as Jharkhand (2000), Chhattisgarh (2000), Uttarakhand (2000), and Telangana (2014), aimed to address governance issues, regional imbalances, and economic underdevelopment. The economic impact of such reorganizations remains a subject of debate.

Positive Impacts

- Positive Impact on Economic Growth: Smaller states have shown higher economic growth due to better administrative efficiency and focused policy implementation. Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand leveraged their mineral resources for industrial development.

- Improved Governance and Infrastructure: Creation of new states has enhanced governance, improved law and order, and accelerated infrastructure development due to targeted policy interventions. Uttarakhand witnessed rapid growth in tourism and hydroelectric projects post-formation.

- Balanced Regional Development: Smaller states allowed better allocation of resources and attention to neglected regions, reducing inter-regional disparities. Telangana saw an increase in agricultural productivity and IT sector growth post-formation.

- Enhanced Local Participation: Smaller states have encouraged local political leadership and participation, fostering economic empowerment and grassroots development.

Negative Impacts

- Rise in Administrative Costs: New states require setting up of separate administrative structures, increasing costs related to governance and public services. Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh faced initial financial burdens due to administrative restructuring.

- Political and Economic Instability: Division of resources and revenue-sharing issues between parent and newly formed states can lead to political and economic instability. The division of Hyderabad between Telangana and Andhra Pradesh led to prolonged financial and political disputes.

- Resource Distribution Challenges: Natural resource distribution and water-sharing disputes between parent and new states, such as the Krishna River dispute between Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, pose long-term economic challenges.

While the formation of new states has led to improved governance, economic growth, and regional development, challenges related to administrative costs, political instability, and resource disputes highlight the need for careful planning and equitable distribution of resources.

Conclusion

The reorganisation of states in India has been a pivotal aspect of post-independence nation-building. Starting with the linguistic reorganisation in 1956, it showcased the Indian state’s ability to adapt to regional aspirations within a constitutional and democratic framework. This process helped strengthen federalism, promote administrative efficiency, and maintain national unity amidst vast linguistic, cultural, and ethnic diversity.

However, the journey has also presented challenges—rising regionalism, uneven development, and persistent demands for new states. These issues highlight the need for a balanced approach that respects regional identities while ensuring inclusive governance and national integration. Going forward, any further reorganisation must be guided by the principles of constitutionalism, federal harmony, developmental justice, and political stability, ensuring that India’s unity continues to thrive through its diversity.

Related FAQs of REORGANISATION OF STATES

After independence in 1947, India inherited a mix of British provinces and over 500 princely states. These divisions were based on colonial convenience, not on cultural or linguistic identity. Reorganising states was essential for better governance, national integration, and giving linguistic and cultural groups fair administrative representation.

The death of Potti Sriramulu in 1952, after a hunger strike demanding a separate Telugu-speaking state, sparked public unrest and forced the government to create Andhra State in 1953. This event led to the formation of the States Reorganisation Commission in 1953, which recommended reorganisation of states on linguistic lines, resulting in the States Reorganisation Act of 1956.

It’s a mix. Linguistic reorganisation strengthened democracy by giving people a stronger cultural identity and sense of belonging, improving administrative efficiency. However, it also led to sub-nationalism, regional political parties, and inter-state disputes (like the Cauvery water issue). So, while unity was preserved, new challenges emerged.

India has continued to address demands for statehood through democratic and constitutional means. States like Gujarat and Maharashtra (1960), Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand, Jharkhand (2000), and Telangana (2014) were formed to address regional, linguistic, and developmental aspirations. These changes show India’s flexibility in accommodating diversity while upholding federal principles.

Persistent demands like Gorkhaland, Vidarbha, and Bundelkhand show that regional imbalances and identity politics remain unresolved. The challenge is balancing these aspirations with national unity, avoiding excessive fragmentation, and ensuring equitable development through effective governance and cooperative federalism.