POVERTY & HUNGER GOVERNANCE

Poverty and hunger are two deeply interlinked issues that continue to pose significant challenges to governance and public policy in India. While poverty limits access to food, education, healthcare, and dignified living, hunger is one of its most visible and severe manifestations. Despite improvements in GDP and targeted welfare programs, millions still suffer from chronic food insecurity, undernutrition, and inadequate caloric intake. These problems are particularly severe among marginalized groups, including women, children, SCs, STs, and the rural poor.

Good governance plays a critical role in addressing these issues by ensuring effective implementation of welfare schemes, transparency in service delivery, and community participation. With the global commitment to SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), India’s policy interventions must aim at long-term structural solutions such as land reforms, sustainable agriculture, universal PDS, and improved nutrition governance.

Poverty in India

Poverty in India represents a multifaceted challenge that goes beyond income deficiency—it includes lack of access to basic needs such as healthcare, education, clean water, and dignified living conditions. Despite notable economic growth and policy reforms, a large segment of the population continues to live under conditions of deprivation, particularly in rural areas, urban slums, and among socially marginalized groups. Structural inequalities, unemployment, inflation, and ineffective delivery of welfare services further aggravate the issue.

Addressing poverty is not only a national imperative but also a global commitment under Sustainable Development Goal 1 (SDG 1): No Poverty, which calls for ending poverty in all its forms everywhere by 2030. India’s progress on this front directly influences global targets due to its demographic weight. Hence, integrating poverty alleviation with strategies like financial inclusion, universal basic services, social safety nets, and sustainable livelihoods is essential for ensuring inclusive development and social equity.

Types of Poverty

Poverty is a complex and multifaceted issue that impacts individuals differently based on their socio-economic and geographical conditions. Understanding its various types is crucial for designing targeted and effective poverty alleviation policies.

- Absolute Poverty – A condition where individuals are unable to meet basic needs like food, clothing, and shelter; measured against a fixed standard such as the World Bank’s $2.15/day threshold.

- Relative Poverty – Defined in relation to societal standards; people are considered poor if their income is significantly below the national average, highlighting income inequality.

- Urban Poverty – Found in cities where high living costs, informal settlements, and job insecurity prevail; slum dwellers and migrants are particularly affected.

- Rural Poverty – Predominant in villages with limited access to land, education, and healthcare; often linked with agrarian distress and seasonal unemployment.

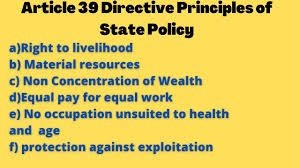

Constitutional and Legal Provisions

India’s constitutional vision of justice—social, economic, and political—guides its poverty alleviation strategies. Several constitutional directives and legal frameworks empower the state to ensure basic welfare and dignity for all, especially the marginalized.

- Article 21 – Guarantees the Right to Life and Personal Liberty, interpreted by the Supreme Court to include the right to live with dignity, access to food, shelter, and livelihood.

- Article 39(b) & (c) – Directs the state to ensure equitable distribution of resources and prevent concentration of wealth.

- Article 41 – Promotes the right to work, education, and public assistance in case of unemployment, old age, or sickness.

- Article 43 – Encourages the state to secure a living wage and decent standard of life for all workers.

- National Food Security Act, 2013 – Aims to provide subsidized food grains to around two-thirds of the population, ensuring food security as a legal right.

- MGNREGA Act, 2005 – Provides a legal guarantee of 100 days of wage employment annually to rural households, enhancing livelihood security.

- Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009 (RTE) – Ensures access to free and quality education, a key tool for long-term poverty eradication.

Poverty Estimation in India

Accurate poverty estimation is crucial for designing targeted welfare programs and tracking socio-economic progress. Over the years, various expert committees have been constituted in India to define, measure, and refine poverty lines based on changing socio-economic realities.

- Planning Commission (1970s–2000s) – Used calorie-based norms (2,400 kcal rural, 2,100 kcal urban) to define poverty lines, using NSSO data on consumption expenditure.

Tendulkar Committee (2009) – Shifted focus from calorie intake to broader consumption-based parameters, factoring in education, health, and shelter; suggested a mixed reference period method.

Tendulkar Committee (2009) – Shifted focus from calorie intake to broader consumption-based parameters, factoring in education, health, and shelter; suggested a mixed reference period method.- Rangarajan Committee (2014) – Recommended higher poverty lines and included food, education, health, transport, and rent expenditure; used the Modified Mixed Reference Period (MMRP).

- Alkire-Foster Method (Global MPI) – Used by UNDP to measure Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) focusing on health, education, and living standards; India adopted it for global comparisons.

- Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) & Consumption Expenditure Surveys (CES) – Provide contemporary data for poverty-related analysis, though recent CES reports have faced delays or withholding.

- NITI Aayog’s MPI (2021 onward) – India’s official multidimensional poverty estimate based on 12 indicators across health, education, and standard of living—aligning with SDG-1 goals.

Causes of Poverty

Poverty in India is a complex and multidimensional issue rooted in a combination of historical, structural, economic, and social factors. Understanding these causes is crucial to formulating effective poverty alleviation strategies and achieving SDG-1: No Poverty.

- Historical and Colonial Legacy – Colonial exploitation drained India’s wealth, disrupted traditional economies, and created structural inequalities that persisted post-Independence.

- Unemployment and Underemployment – Lack of stable jobs, especially in rural areas, along with disguised unemployment in agriculture, leads to low and uncertain incomes.

- Low Agricultural Productivity – Fragmented landholdings, lack of irrigation, credit, and modern technology reduce productivity, affecting the majority dependent on agriculture.

- Inequitable Distribution of Resources – Skewed access to land, education, and capital creates systemic exclusion, keeping vulnerable sections in poverty cycles.

- Rapid Population Growth – High population pressure on limited resources dilutes developmental gains and increases the demand-supply gap in employment and services.

- Inflation and Price Volatility – Rising food and fuel prices disproportionately affect the poor, reducing their real incomes and access to basic necessities.

- Low Human Capital Development – Poor access to quality education and healthcare reduces productivity and limits upward social mobility.

- Social Discrimination – Caste, gender, and ethnic-based exclusion marginalize communities, restricting their access to opportunities and welfare benefits.

Poverty Alleviation Strategies since Independence

India has adopted a series of evolving poverty alleviation strategies since independence, ranging from rural development programs to rights-based entitlements. These efforts align with global commitments like SDG-1 (No Poverty) and SDG-10 (Reduced Inequalities), aiming to reduce multidimensional poverty across regions and communities.

Rural Development & Employment Schemes – Early initiatives like the Community Development Programme (1952), followed by IRDP and JRY, focused on rural infrastructure, employment, and asset creation for the poor.

Rural Development & Employment Schemes – Early initiatives like the Community Development Programme (1952), followed by IRDP and JRY, focused on rural infrastructure, employment, and asset creation for the poor.- MGNREGA (2005) – A landmark rights-based approach that guarantees 100 days of wage employment annually to rural households, ensuring livelihood security and rural empowerment.

- Targeted Food Security – Schemes like TPDS (1997) and ONORC provide subsidized food to BPL families and migrants, addressing hunger and malnutrition as part of poverty reduction.

- Livelihood Missions – NRLM and NULM focus on promoting self-employment, SHGs, financial inclusion, and skill development among rural and urban poor.

- Affordable Housing – PMAY (Urban & Gramin) supports low-income families in accessing pucca houses through subsidies and interest benefits.

- Direct Benefit Transfers & JAM Trinity – Aadhar-linked DBT system ensures timely delivery of welfare benefits and subsidies, reducing corruption and leakages.

- Social Protection Schemes – Initiatives like Ayushman Bharat and PM Garib Kalyan Yojana enhance health security and income support for vulnerable populations, especially during crises like COVID-19.

Role of NITI Aayog

NITI Aayog, as India’s premier policy think tank, plays a central role in localizing and monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Goal 1 – No Poverty. It acts as a bridge between national policies and global development targets, ensuring inclusive and sustainable growth.

- SDG Index and Monitoring – NITI Aayog releases the India SDG Index to track state-wise progress on SDG 1 and other goals, fostering competitive federalism and targeted interventions.

- Policy Advisory and Planning – It advises central and state governments on pro-poor policies and evidence-based poverty alleviation strategies by integrating economic reforms with social safety nets.

- Convergence Platform – It promotes coordination between ministries, states, and stakeholders to align existing welfare schemes like MGNREGA, PMAY, and DBT with the objectives of SDG 1.

- Data-Driven Governance – Through real-time dashboards and data analytics, NITI Aayog strengthens outcome-based monitoring of poverty reduction programs across rural and urban areas.

- Focus on Aspirational Districts – It leads the Aspirational Districts Programme, targeting the most backward regions with focused development in health, education, and income—key to achieving SDG 1.

Collaborations with UN and NGOs – It partners with international organizations like UNDP and civil society to mobilize resources, build capacities, and ensure grassroots-level implementation of SDG 1.

Collaborations with UN and NGOs – It partners with international organizations like UNDP and civil society to mobilize resources, build capacities, and ensure grassroots-level implementation of SDG 1.- Vision Documents – NITI Aayog’s “Strategy for New India @75” and Viksit Bharat 2047 framework aim at eliminating extreme poverty and promoting inclusive growth through long-term planning and reforms.

Evaluation and Monitoring Mechanisms

Effective monitoring and evaluation are essential for assessing the impact and efficiency of poverty alleviation programmes. In India, both institutional and technological mechanisms have been developed to ensure transparency, accountability, and data-driven policymaking.

- Third-Party Evaluations – NITI Aayog and Ministry of Rural Development engage independent institutions and think tanks to conduct impact assessments of major schemes like MGNREGA, NRLM, and PMAY.

- Social Audits – Mandated under MGNREGA and other schemes, social audits involve community participation in evaluating the delivery and effectiveness of public services, ensuring grassroots accountability.

- Public Financial Management System (PFMS) – This real-time online platform tracks fund flow, ensures timely payments under welfare schemes, and reduces leakages in the system.

- MIS & Dashboards – Ministries operate Management Information Systems (MIS) and online dashboards to monitor key indicators, beneficiary coverage, and real-time performance of schemes.

- Performance-Based Ranking – States and districts are ranked based on development outcomes (e.g., SDG India Index, Aspirational Districts rankings), encouraging data-driven governance and improvements.

Role of Civil Society and NGOs

Civil society organizations and NGOs complement government efforts by acting as catalysts, watchdogs, and implementers in the fight against poverty and hunger. Their grassroots presence and flexibility make them vital in reaching marginalized populations.

- Service Delivery and Implementation Support – NGOs often implement livelihood programs, skill development initiatives, and nutritional interventions, especially in remote and tribal areas where state presence is limited.

- Advocacy and Awareness – They raise awareness about rights, entitlements, and welfare schemes among vulnerable populations, ensuring better access and utilization.

- Social Mobilization – NGOs promote community participation, form Self-Help Groups (SHGs), and enable collective action, which are crucial for sustainable poverty reduction.

- Monitoring and Feedback – Civil society plays a watchdog role by identifying policy gaps, conducting parallel evaluations, and providing constructive feedback to improve program outcomes.

- Innovation and Experimentation – NGOs often pilot innovative models of poverty alleviation—such as community kitchens, microfinance, and cooperative farming—that can be scaled by governments.

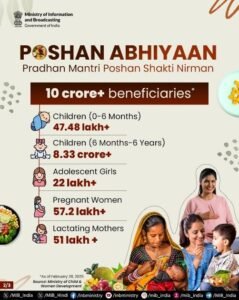

- Partnership with Government – Through Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) and MoUs, NGOs and CSOs work with governments under schemes like DAY-NRLM, Poshan Abhiyaan, and Aspirational Districts Program.

These mechanisms, when aligned, create a comprehensive ecosystem for tackling poverty through collaboration, transparency, and citizen-centric governance.

Challenges in Eradicating Poverty

Despite decades of policy interventions, poverty remains a persistent issue in India due to structural, administrative, and socio-economic factors. Addressing these challenges is critical to achieving SDG Goal 1: No Poverty.

- Informal Employment and Underemployment – A large segment of India’s workforce is engaged in informal jobs with low wages, no social security, and limited upward mobility, perpetuating working poverty.

- Regional Disparities – States like Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh continue to have high poverty rates compared to more developed states, indicating uneven growth and inadequate redistribution of resources.

- Ineffective Targeting and Leakages – Many poverty alleviation schemes face issues like ghost beneficiaries, exclusion of deserving households, and leakages in fund flow due to poor identification and delivery mechanisms.

- Low Human Capital Development – Poor access to quality education, healthcare, and nutrition hinders the capacity of individuals to break out of the poverty cycle and access gainful employment.

- Gender Inequality and Social Exclusion – Women, Dalits, Adivasis, and persons with disabilities face discrimination in accessing livelihoods, resources, and entitlements, worsening poverty among marginalized groups.

Urban Poverty and Slums – Rapid urbanization has led to the proliferation of slums with inadequate housing, sanitation, and job opportunities, creating new dimensions of urban poverty that are harder to monitor and address.

Urban Poverty and Slums – Rapid urbanization has led to the proliferation of slums with inadequate housing, sanitation, and job opportunities, creating new dimensions of urban poverty that are harder to monitor and address.- Climate Vulnerability and Agrarian Distress – Poor households are more exposed to natural disasters, droughts, and crop failures, especially in rural areas dependent on rain-fed agriculture, which exacerbates their economic vulnerability.

These challenges underline the need for a multidimensional, inclusive, and adaptive approach to poverty alleviation that goes beyond income metrics and addresses structural inequalities.

Way Forward

To effectively tackle poverty and move towards the Sustainable Development Goal of “No Poverty,” India needs a multidimensional, inclusive, and sustainable strategy. The approach should integrate economic growth with social equity, empowerment, and institutional reforms.

- Adopt a Multidimensional Poverty Framework – Use indicators beyond income, such as health, education, housing, and nutrition (as per MPI), to better target and design interventions.

- Promote Inclusive and Decentralized Growth – Focus on backward regions, rural infrastructure, and agro-based industries to ensure balanced regional development and rural employment.

- Strengthen Social Safety Nets – Expand coverage, efficiency, and portability of schemes like PDS, MGNREGA, PMGKAY, and DBT with improved grievance redressal and transparency.

- Invest in Human Capital – Enhance spending on education, health, and nutrition to empower people with skills and capabilities needed to escape intergenerational poverty.

- Empower Women and Marginalized Groups – Promote financial inclusion, land rights, SHGs, and entrepreneurship among women, SCs, STs, and PwDs to bridge socio-economic gaps.

- Leverage Digital Technology and Data – Use Aadhaar-linked platforms, JAM trinity, real-time data, and social audits to monitor poverty programs, reduce leakages, and improve delivery.

- Strengthen Convergence and Governance – Ensure inter-sectoral coordination among ministries, promote NITI Aayog’s SDG localization efforts, and strengthen local governments for bottom-up planning and accountability.

Together, these measures can shift the poverty discourse from charity to capability-building and from subsidies to empowerment, ensuring that no one is left behind in India’s development journey.

Hunger

Hunger is a multidimensional issue that extends beyond the absence of food—it includes chronic undernourishment, food insecurity, and malnutrition. Malnutrition manifests in various forms: undernutrition (wasting, stunting, underweight), micronutrient deficiencies (hidden hunger), and overnutrition (obesity). In India, despite being a major agricultural economy, millions face hunger and malnutrition due to poverty, inequitable food distribution, poor dietary practices, and lack of awareness, especially among vulnerable groups like children, women, and the elderly.

The crisis of malnutrition remains alarming—NFHS-5 data shows that over 35% of Indian children under 5 are stunted, and over 32% are underweight, highlighting the severity of the problem. Hunger and malnutrition not only hinder physical growth but also impair cognitive development, learning capacity, and future productivity. Addressing this issue is crucial to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger) and is interconnected with other SDGs like Health (SDG 3), Education (SDG 4), and Poverty Reduction (SDG 1). A multi-sectoral, nutrition-sensitive, and rights-based strategy is essential for a hunger-free and healthy India.

The crisis of malnutrition remains alarming—NFHS-5 data shows that over 35% of Indian children under 5 are stunted, and over 32% are underweight, highlighting the severity of the problem. Hunger and malnutrition not only hinder physical growth but also impair cognitive development, learning capacity, and future productivity. Addressing this issue is crucial to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 2 (Zero Hunger) and is interconnected with other SDGs like Health (SDG 3), Education (SDG 4), and Poverty Reduction (SDG 1). A multi-sectoral, nutrition-sensitive, and rights-based strategy is essential for a hunger-free and healthy India.

Types of Hunger

Hunger is a complex phenomenon that affects people in different ways. Understanding its types helps in designing targeted interventions and policy responses.

- Chronic Hunger – It refers to a long-term or persistent lack of adequate food. People suffering from chronic hunger consume insufficient food over extended periods, often leading to malnutrition and stunted growth.

- Hidden Hunger – This occurs when people consume enough calories but lack essential micronutrients like iron, vitamin A, and iodine. It is common among poor populations and leads to weakened immunity, fatigue, and developmental issues.

- Acute Hunger – It results from emergencies like natural disasters, conflicts, or displacement. It is severe and sudden, leading to wasting, starvation, and often requiring urgent humanitarian intervention.

- Seasonal Hunger – Linked to agricultural cycles, it occurs during lean periods between harvests. This type is prevalent among small and marginal farmers and agricultural labourers who lack food security during off-seasons.

- Urban Hunger – Found in urban slums and informal settlements, it is driven by unemployment, high food prices, and poor access to nutritional food. Though less visible than rural hunger, it is rising due to rapid urbanization and inequality.

Constitutional Provisions

India’s Constitution reflects the vision of a welfare state and ensures socio-economic justice for all, including protection against hunger and poverty. Several provisions either directly or indirectly address the issue of food security and poverty alleviation:

- Article 21 – Guarantees the Right to Life and Personal Liberty, which has been judicially interpreted to include the right to live with dignity, encompassing the right to food and nutrition (PUCL vs Union of India case).

Article 39(a) – Part of the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP), it directs the state to ensure that citizens have the right to adequate means of livelihood.

Article 39(a) – Part of the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP), it directs the state to ensure that citizens have the right to adequate means of livelihood.- Article 41 – Obliges the state to provide public assistance in cases of unemployment, old age, sickness, and disablement, thereby supporting vulnerable sections.

- Article 47 – Specifically directs the state to raise the level of nutrition and the standard of living of its people and to improve public health, marking it a primary duty.

- Article 15(3) – Allows the state to make special provisions for women and children, which can be linked to tackling child malnutrition and maternal hunger through schemes like ICDS and MDM.

| Global Indices and India’s Position |

|

India’s status concerning hunger and food security is assessed through various global indices, notably the Global Hunger Index (GHI) and the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report. Global Hunger Index (GHI) The GHI is a peer-reviewed annual report that measures and tracks hunger at global, regional, and national levels. It combines four indicators: undernourishment, child wasting, child stunting, and child mortality.

State of Food Security and Nutrition (SOFI) Report The SOFI report, jointly published by international agencies like FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO, provides a comprehensive analysis on global food security and nutrition.

These indices underscore the ongoing challenges India faces in combating hunger and malnutrition, emphasizing the need for sustained policy interventions and effective implementation of food security programs. |

Major Government Schemes

The Government of India has launched several targeted schemes to address hunger and malnutrition, focusing on food distribution, nutrition supplementation, and community-based support mechanisms. These schemes are critical to achieving SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and ensuring food security for all.

Public Distribution System (PDS) – Ensures subsidized food grains (rice, wheat, etc.) to poor households through a nationwide ration network, improving food access among the economically vulnerable.

Public Distribution System (PDS) – Ensures subsidized food grains (rice, wheat, etc.) to poor households through a nationwide ration network, improving food access among the economically vulnerable.- National Food Security Act (NFSA), 2013 – Provides legal entitlements to 75% rural and 50% urban population to receive subsidized food grains under PDS, with special provisions for women and children.

- Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) – Delivers nutrition, preschool education, immunization, and health check-ups to children under six and pregnant/lactating mothers through Anganwadi centres.

- Mid-Day Meal Scheme (MDMS) – Offers cooked meals to school children from Class I–VIII to improve nutritional levels and encourage school attendance, especially in economically weaker sections.

- POSHAN Abhiyaan (National Nutrition Mission) – Aims to reduce stunting, wasting, and anemia among children and women by promoting a convergence of nutrition-related schemes and using data-driven monitoring.

- PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) – Launched during the COVID-19 pandemic to provide free additional food grains to over 80 crore beneficiaries under NFSA.

- National Nutrition Mission – Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 – A revamped version of earlier schemes focusing on smart Anganwadis, community participation, and technology-based monitoring for better outcomes in nutrition delivery.

These schemes form the backbone of India’s anti-hunger strategy, combining food security with nutritional well-being across vulnerable groups.

Institutional Mechanisms

India has established a robust institutional framework to combat hunger and malnutrition through coordination among central ministries, state governments, local bodies, and frontline service providers. These institutions ensure policy formulation, scheme implementation, monitoring, and community engagement.

- Ministry of Women and Child Development (MoWCD) – Nodal ministry for implementing schemes like ICDS and POSHAN Abhiyaan, focusing on the nutritional needs of children, pregnant women, and lactating mothers.

- Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution – Manages the Public Distribution System (PDS) and oversees implementation of the National Food Security Act to ensure food access to the poor.

- Food Corporation of India (FCI) – Responsible for procurement, storage, and distribution of food grains to maintain buffer stocks and support PDS operations.

- National Nutrition Mission Executive Committee (NNMEC) – Provides oversight and inter-ministerial coordination for nutrition interventions under POSHAN Abhiyaan.

- State Food Commissions – Established under the NFSA to monitor and evaluate implementation at the state level, handle grievances, and ensure accountability.

- Anganwadi Centres – Operated by local women workers, these centres deliver nutrition, preschool education, and health services under ICDS in villages and urban slums.

- Nutrition Resource Centres – Set up at state and district levels to provide technical support, data analysis, and capacity building for effective nutrition programming.

These mechanisms play a vital role in operationalizing India’s anti-hunger initiatives, ensuring last-mile delivery, convergence across departments, and accountability in addressing nutritional challenges.

Monitoring and Evaluation Tools

Monitoring and evaluation are essential for ensuring the effectiveness, transparency, and accountability of hunger and nutrition-related programs. India has developed multiple tools and mechanisms at various administrative levels to track progress, identify gaps, and take corrective action.

POSHAN Tracker – A real-time digital monitoring platform under POSHAN Abhiyaan that tracks service delivery and nutrition indicators at Anganwadi centres.

POSHAN Tracker – A real-time digital monitoring platform under POSHAN Abhiyaan that tracks service delivery and nutrition indicators at Anganwadi centres.- Rapid Reporting System (RRS) – A web-based monitoring tool used for tracking the delivery of services under the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme.

- Health Management Information System (HMIS) – Managed by the Ministry of Health, it collects data from health facilities to monitor maternal and child health outcomes, including nutrition indicators.

- Annual Health Survey (AHS) and National Family Health Survey (NFHS) – Large-scale surveys that provide valuable data on nutritional status, child health, and service coverage, crucial for policy-making and mid-course corrections.

- Nutrition Surveillance Systems – Used in specific states to monitor undernutrition and food insecurity trends, often in collaboration with international agencies.

- Third-Party Evaluations – Independent agencies are engaged to assess the impact, efficiency, and relevance of major nutrition and food security programs, ensuring objectivity and transparency.

- Jan Andolan and Community-Based Monitoring – Grassroots involvement through local governance institutions and civil society to track services, raise awareness, and ensure community ownership of nutrition outcomes.

These tools together create a data-driven, responsive governance ecosystem to fight hunger and malnutrition effectively across India.

Role of Supreme Court and Food Security Campaigns

The Supreme Court of India has played a transformative role in upholding the Right to Food as part of the Right to Life under Article 21 of the Constitution. One of the most significant interventions came through the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) vs. Union of India case (2001), which became a landmark in the history of food security jurisprudence in India.

- PUCL Case (2001) – Filed during a period of widespread drought and starvation, this Public Interest Litigation (PIL) demanded that surplus food stocks be used to prevent hunger. The Court acknowledged food as a fundamental right under Article 21 and issued a series of interim orders converting government food and nutrition schemes into enforceable entitlements.

Impact on Policy and Governance – The PUCL case led to legal enforcement of schemes like the Mid-Day Meal Scheme, Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), and the Public Distribution System (PDS). It directed all states to implement these schemes universally and ensure transparency and accountability mechanisms like vigilance committees and social audits.

Impact on Policy and Governance – The PUCL case led to legal enforcement of schemes like the Mid-Day Meal Scheme, Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), and the Public Distribution System (PDS). It directed all states to implement these schemes universally and ensure transparency and accountability mechanisms like vigilance committees and social audits.- Role in Shaping NFSA 2013 – The judicial activism around the Right to Food laid the foundation for the National Food Security Act, 2013, which made subsidized foodgrain a legal right for two-thirds of India’s population and recognized nutritional support for children, pregnant women, and lactating mothers.

Through the PUCL case and its follow-up orders, the Supreme Court has acted as a powerful guardian of socio-economic rights, ensuring the state’s responsibility in combating hunger and advancing food justice in India.

Role of NGOs and Community Kitchens

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and community-driven initiatives have emerged as crucial actors in bridging gaps in food access, especially for vulnerable populations. Their grassroots presence and innovative approaches complement state efforts in addressing hunger and malnutrition.

- Community Kitchens – NGOs like Akshaya Patra, Robin Hood Army, and state-run initiatives such as Tamil Nadu’s Amma Canteens and Kerala’s Kudumbashree have demonstrated scalable models of providing nutritious, affordable, or free meals to the poor, homeless, daily wage earners, and disaster-affected populations.

- Outreach and Awareness – NGOs often run awareness campaigns on nutrition, breastfeeding, and hygiene. They mobilize communities to demand food entitlements and facilitate access to schemes like the Public Distribution System (PDS), Mid-Day Meals, and ICDS.

- Innovation and Monitoring – Many NGOs engage in policy advocacy and innovation—like using mobile food vans, app-based donations, and tech-enabled tracking of food wastage. They also assist in conducting social audits, monitoring delivery systems, and reporting leakages and exclusion errors.

Overall, NGOs and community kitchens act as vital partners in creating hunger-free communities by ensuring last-mile delivery of food and promoting community participation in food governance.

Challenges

Despite significant efforts by the government and civil society, India continues to face persistent challenges in eradicating hunger and malnutrition. These issues are multidimensional, rooted in socio-economic inequalities, and compounded by systemic inefficiencies.

- Inefficient Public Distribution System (PDS) – Issues like leakages, corruption, identification errors, and exclusion of genuine beneficiaries undermine the effectiveness of food delivery.

- Malnutrition and Hidden Hunger – While calorie intake may be met, micronutrient deficiencies (like iron, vitamin A, and zinc) remain widespread, especially among women and children, leading to stunting, wasting, and anemia.

- Climate Change and Agricultural Instability – Irregular monsoons, declining soil fertility, and crop failures due to extreme weather events impact food production and availability, worsening hunger in rural areas.

- Lack of Dietary Diversity – Cultural habits, poverty, and inadequate awareness often result in diets lacking in fruits, vegetables, and proteins, affecting overall nutritional outcomes.

- Data Gaps and Monitoring – Absence of real-time data on nutrition indicators and ineffective monitoring frameworks hinder timely interventions and policy reforms.

- Urban-Rural and Regional Disparities – Hunger is more acute in tribal and remote areas, with states like Bihar, Jharkhand, and Madhya Pradesh facing higher levels of food insecurity and undernutrition.

- Gendered Dimension of Hunger – Women and girls often eat last and least in poor households. Lack of targeted nutrition and maternal care programs exacerbates the intergenerational cycle of malnutrition.

| Best Practices |

|

Tamil Nadu Noon Meal Scheme: Introduced in 1982, this pioneering initiative provides hot, cooked meals to school children to combat classroom hunger and improve attendance. It ensures children receive essential nutrients, reducing dropout rates and encouraging education among marginalized communities. The scheme has inspired similar programs across India, including the Mid-Day Meal Scheme at the national level. Chhattisgarh Food Security Model: Chhattisgarh has implemented one of the most effective food security systems in India. It revamped its Public Distribution System (PDS) with digitization, doorstep delivery of food grains, and biometric authentication. The state ensures universal coverage with subsidized rice, pulses, and salt, leading to near elimination of hunger-related starvation deaths and improved food access in tribal and rural areas. |

Way Forward

Addressing hunger and malnutrition in India requires a multi-dimensional strategy rooted in inclusivity, decentralization, and data-backed planning. Moving forward, efforts must prioritize nutrition security alongside food security for long-term human development.

- Holistic Nutrition Approach – Move beyond calorie sufficiency to ensure intake of proteins, micronutrients, and balanced diets, especially for vulnerable groups like children, women, and the elderly.

- Strengthen Last Mile Delivery – Improve efficiency and transparency in schemes like ICDS and PDS through digital tracking, grievance redressal, and community audits to ensure real beneficiaries are served.

- Community Participation – Empower local bodies, SHGs, and community kitchens to ensure decentralized food security and local nutrition solutions based on region-specific needs.

- Focus on Maternal and Child Health – Integrate nutrition with healthcare services for pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children under 5 through campaigns like POSHAN Abhiyan.

- Food Fortification & Diversification – Promote fortified staples and locally available diverse food items (millets, pulses, vegetables) in public nutrition schemes.

- Data-Driven Targeting – Use real-time data for identifying malnutrition hotspots and vulnerable households to target interventions effectively.

- Collaboration with Private Sector & NGOs – Leverage CSR, technological innovation, and outreach capabilities of NGOs and private partners for scalable and sustainable hunger solutions.

Conclusion

Poverty and hunger are deeply intertwined governance challenges that reflect socio-economic inequality and systemic deprivation. Despite decades of targeted policies and programs, a significant section of the population continues to struggle for basic needs, dignity, and opportunity. The persistence of poverty and hunger undermines democratic ideals and hampers inclusive growth.

Addressing these issues requires more than economic growth—it demands a multi-dimensional, rights-based, and inclusive governance approach. Strengthening welfare delivery, empowering local institutions, ensuring accountability, and aligning efforts with Sustainable Development Goals—particularly SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger)—are critical to transforming India into a just, equitable, and resilient society.

Relate FAQs of POVERTY & HUNGER GOVERNANCE

The key causes of poverty in India include unemployment, low agricultural productivity, unequal resource distribution, population pressure, inflation, social discrimination, poor human capital development, and underemployment in the informal sector.

Poverty refers to the inability to meet basic needs like food, shelter, education, and healthcare, while hunger is a direct outcome of poverty, involving lack of sufficient food, undernutrition, and food insecurity. Hunger is both a cause and effect of poverty.

Major schemes include MGNREGA (employment guarantee), National Food Security Act (NFSA), Public Distribution System (PDS), Ayushman Bharat (healthcare), PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (free food grains), POSHAN Abhiyaan (nutrition), and Mid-Day Meal Scheme (school children nutrition).

In the Global Hunger Index 2024, India ranked 105th out of 127 countries, with a score of 27.3, indicating a “serious” level of hunger, despite progress in reducing undernourishment since 2000.

India can address poverty and hunger through increasing human capital investment, ensuring efficient welfare delivery, strengthening social safety nets, promoting nutrition security, empowering women, leveraging technology for targeting beneficiaries, and enhancing community participation through social audits and grassroots governance.