Administrative Unification under the British Empire

Administrative Unification under the British Empire

The establishment of the British Empire allowed not only the political unification of the country but also Administrative and Economic unification. Pre-British India was divided into many feudal states, frequently struggling among themselves to extend their boundaries.

A conception of unity existed, but that was limited to ‘geographical Unity’ and the religious-cultural unity. Even though monarchs like Ashoka, Samudragupta, and Akbar attempted to unify the country politically, the political and administrative unity achieved was only nominal.

The British conquest of India between 1757 and 1857 led to the establishment of a centralised state, which brought about a real political unification of the country for the first time in Indian history. A unified economy and modern means of communication like Telegram and railways may have helped the British achieve political and administrative unity.

In this article, we shall study these changes introduced with the establishment of British rule.

Legislative and Constitutional Reforms

1. The Act for The Better Government of India, 1858

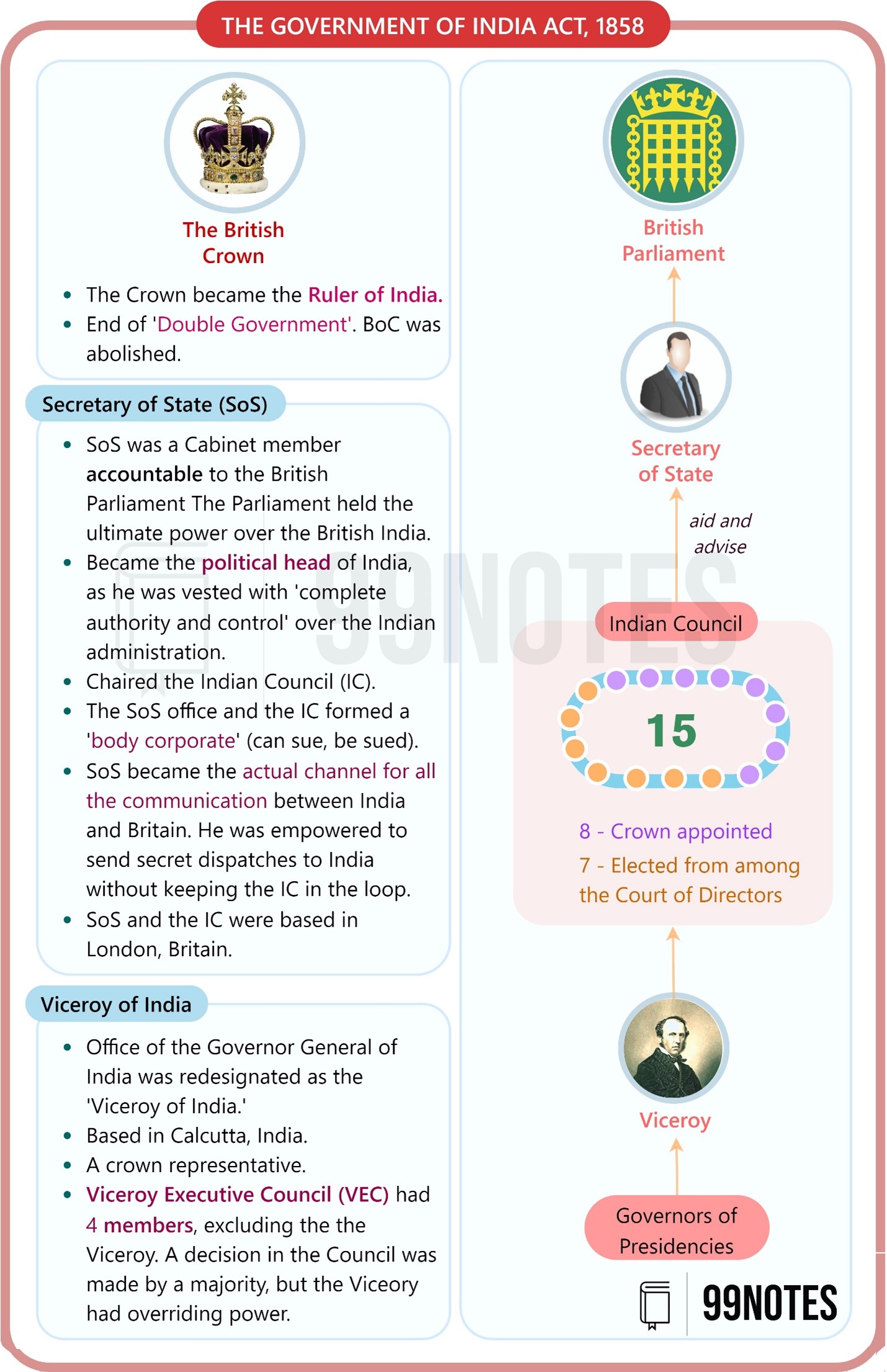

The Government of India Act of 1858 passed the effective control from the East India Company to the British Crown. The court of directors and the board of directors were dissolved, and its place was taken by the secretary of state of India and his council of 15.

The Governor-General was now called the Viceroy. The Viceroy was reduced to a subordinate position in relation to the British government.

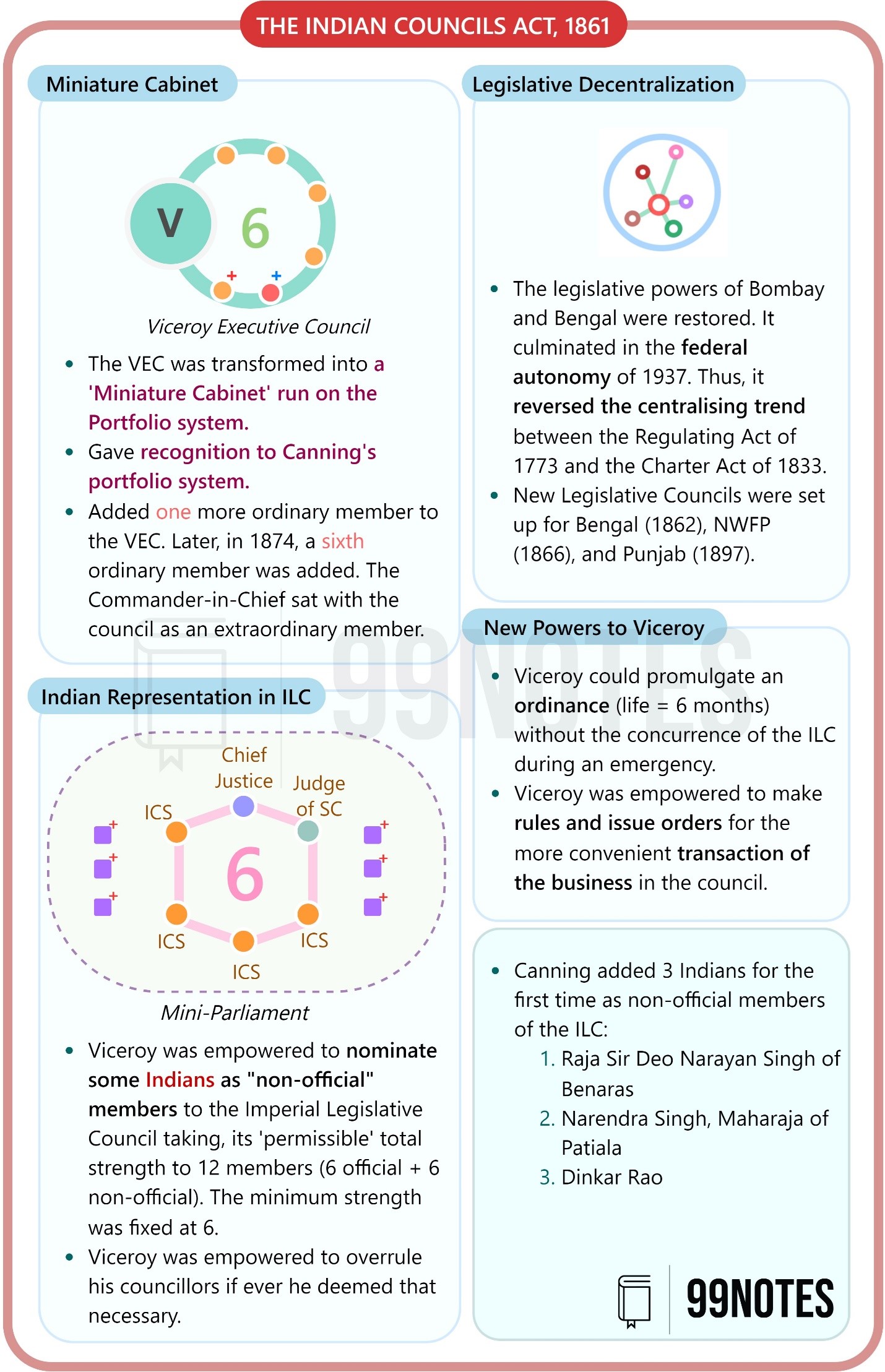

2. Indian Councils Act, 1861

The Indian Councils Act of 1861 reversed the centralising trend in the administration that began with the Regulating Act of 1773. It made the following provisions:

- It revived the legislative powers of the Madras and Bombay presidencies, which were taken away by the Charter Act of 1833. Legislative councils in other Provinces like Bengal (1862) and NWFP (1886) were introduced.

- For legislative purposes, the Governor-General’s council could have 6-12 additional members, of which half of them were to be non-official.

- For the first time, 3 Indians, Raja of Benaras, Maharaja of Patiala & Sir Dinkar Rao, were included in the legislative council.

- A fifth member, who was to be a jurist, was added to the Viceroy’s executive council.

- A Portfolio system was introduced in which a member of the Viceroy’s council was made in charge of one or more government departments and was authorised to issue orders on behalf of the whole council.

- The Viceroy was given the power to veto the council in certain matters as well as the power to issue ordinances.

After 1861, several small steps were taken to improve the administrative system in India under lord Mayo and Rippon, and several powers were transferred to the provincial level at the administrative level. However, no major legislative changes were introduced all this while. The next major legislative Change came in 1892.

3. Indian Councils Act, 1892

In 1885, all the major nationalist leaders formed the Indian National Congress and demanded the expansion of the legislative councils to give a greater say to the Indians. The Indian Councils Act of 1892 introduced the following changes:

- The number of non-official members was increased in both Central (10-16) and provincial legislatures.

- The functions of the legislative council were increased, and the members could now discuss the budget and pose questions to the executive.

- The principle of representation was introduced, which empowered universities, district boards, municipalities, trade bodies, chambers of commerce, and zamindars to recommend members to the provincial councils.

- An element of the indirect election was accepted in the selection of some non-official members.

Administrative Unification

After the act of 1858, the Viceroy was reduced to a subordinate position, and the secretary of the state now controlled the minutest details of administration.

Since the final authority has now come to reside in London, Indian opinions have had an even lesser impact on policy matters. On the other hand, British industrialists, merchants, and bankers increased their influence over India’s government.

1. Provincial administration

The British had divided India into several provinces, three of which, Bengal, Madras and Bombay, were known as presidencies. The Presidency governments possessed more rights and power than the governments of other provinces.

The Crown appointed the presidency government administered by a Governor and his executive council. In contrast, other provinces were headed by Lieutenant Governors and chief Commissioners appointed by the Governor-General.

The provinces enjoyed a great deal of autonomy before 1833, when their legislative councils were abolished, and their expenditure was subject to strict central control. Finally, the legislative powers were restored in 1861.

Finance was still highly centralised, and the central government exercised strict control over provincial expenditure.

- Lord Mayo took the first step toward decentralisation of Finances in 1871. The provincial governments were granted a fixed share of central revenues for certain services like Police, jails, education, etc.

- Lord Lytton: The policy of Lord Mayo was further pursued by Lord Lytton, who expanded the number of services, the revenue of which was to be transferred to the provinces.

- Lord Rippon: In 1882, Under Rippon, the system of giving fixed grants to the provinces was ended, and, instead, a province was to get the entire income from certain sources or revenue within it. All sources of revenue were divided into general, provincial, and those to be divided between the centre and the province.

However, the central government remained supreme and effectively controlled the Provinces. This is very similar to the structure of federalism that India practices even today.

2. Local government

The first local government in British India was established in Madras in 1687. However, the decentralisation process remained extremely slow; The British Indian government was highly centralised till 1861.

Nevertheless, the governance had to be decentralised for the following reasons:

- Financial distress due to excessive Government expenditure on the Army and Railways led the government to decentralise the administration by promoting local government through municipalities and district boards that would create new sources of finance.

- The Indian nationalists demanded the introduction of modern improvements in civic life.

- To check the Nationalist Movement: It was also thought that associating Indians with the administration in some capacity would check their increasing politicisation.

- To raise local resources: The Mayo Resolution of 1870 stressed the need to introduce self-government in local areas to raise local resources to administer important local services.

Ripon’s resolution of 1882: Eventually, the most significant effort for political decentralisation was made by Lord Rippon, who used to be known as the father of local self-government in British India. He took the following steps:

- Development of local bodies not only to improve administration but also as an instrument of political education.

- Defined powers & functions: The functions and duties of the local governments were defined, and they were entrusted with suitable sources of revenue.

- Non-officials were to be in the majority, and there was a provision for election as well (though not mandatory). Non-officials were to be the chairmen of these bodies.

Later, under Lord Curzon, the official control over local bodies increased. However, the bureaucracy did not share the liberal view of the Viceroy and considered Indians to be unfit for self-government.

3. Civil Services

The members of the Indian Civil Services occupied all positions of power and responsibility. The British considered the occupation of the higher post by Europeans as a necessary condition for maintaining British supremacy in India.

But, a few reluctant attempts were made to share power with Indians:

- The Charter Act of 1853 threw open the recruitment of civil servants for Indians.

- The Proclamation of 1858 declared the intentions of the British to include Indians in offices under civil services.

However, in practice, the doors of civil services for Indians remained barred because of several difficulties. It was only in 1863 that Satyendra Nath Tagore became the first Indian to qualify for Indian civil services. Two central problems prevented Indians from entering into the services:

- The exam was held in England in English and was based on classical learning of Greek and Latin.

- The maximum age for entry into Indian Civil services was gradually reduced from twenty-three in 1859 to nineteen in 1878.

Recognising such challenges, the Indian National Congress demanded increasing the maximum entry age into civil services and holding the exam simultaneously in India and England. Thus, the Aitchison Committee on Public Services (1886) was set up by Dufferin. It recommended the following:

- Classification of services into Imperial civil services exam (examination to be held in England), Provincial civil services (examination to be held in India) and Subordinate civil services (examination to be held in India).

- Raising the age limit to 23.

4. Policy towards Princely states

During the revolt of 1857, the majority of the Princely states remained loyal and even aided the British in suppressing it. As Viceroy Lord Canning put it, “they had acted as breakwaters in the storm”. Thus, the policy of annexation of princely states was abolished, But in terms of power structure, their status was further reduced:

- The policy of subordinate union: Relations with princely states were guided by using and perpetuating them as bulwarks of the Empire and subordinating them entirely to the British authority.

- Their sovereignty was lost as they were made to acknowledge Britain as the Paramount power.

- In 1876, Queen Victoria took the title of Emperor of India (Kaiser-e-Hind) to emphasise British sovereignty over the entire Indian sub-continent.

- Lord Curzon Made it clear that the Princes ruled the state merely as agents of the Crown.

- The British interfered in the day-to-day administration of the princely states through Residents.

-

- One of the motives of the interference was to introduce modern administration to achieve complete integration of India.

- The modern ways of communication and transportation, like railways and telegraphs, further facilitated the encroachment.

- The growth of nationalistic movements in these states provided another motive for intervention.

5. Foreign policy

The development of modern modes of communication and political and administrative consolidation made the British reach India’s natural and geographical boundaries. A strong foreign policy, thus, became one of the foundational elements of the British government for the following reasons:

- Border Defense: It was essential for external defence as well as internal cohesion.

- Promoting the economic interests of the Empire and keeping other European powers at a distance from India often prompted the British Indian government to act aggressively towards its neighbours.

While the Empire’s policy served its interests, ultimately, it was the Indians who had to pay for it. India had to wage war against its neighbours, Indian soldiers had to shed their blood, and Indian taxpayers had to pay for it.

Nepal

In 1814, a border clash between the border police of both countries led to an open war. The Nepalese government had to make peace on British terms. In the treaty of Sagauli in 1816, the Nepalese accepted the following terms:

- A British Resident ceded the Garhwal and Kumaon districts and abandoned claims to the Terai Areas. Kali River formed the natural boundary between India and Nepal.

- Nepal also withdrew from Sikkim.

Burma

Burma’s rich forest resources guided the aggressive and expansionist policy of British India towards Burma and to check French expansion in Burma and the rest of South East Asia.

- First Burma War: The Burmese occupation of Arakan (1785), Manipur (1813) and Assam (1822) led to continuous friction between Bengal and Burma. In 1824, the British declared war on Burma and drove them out of Assam, Arakan, Cachar and Manipur. The Treaty of Yandabo brought peace.

- The second Burma War broke out in 1852 because of British greed for Burmese timber resources and a large market for selling cotton and other manufactured goods. This time, the British gained a decisive victory, and they now controlled Burma’s entire coastline and sea trade. The fear of capture of the Burmese market by the French and Americans made the British merchants in Rangoon press for the annexation of Burma. Finally, in 1885, King Thibaw surrendered, and his dominions were soon annexed to the Indian Empire.

Afghanistan

Afghanistan was located in a strategic geographical position from the British point of view, and therefore, it was in the interest of the British Indian government to control it. It was motivated by two main reasons:

- British influence over Afghanistan was essential for checking Russia’s potential military threat and promoting British commercial interests in Central Asia.

- They wanted a weak and divided Afghanistan that they could easily control.

The conflict started in Phases:

- In the first Anglo-Afghan war, the British managed to capture Kabul in 1842 after initial defeats. However, they arrived at a settlement and recognised Dost Muhammad as the independent ruler of Afghanistan. After suffering vast sums of their revenue in the Afghan war, the British adopted the policy of non-interference.

- Second Anglo-Afghan War: In the 1870s, the British statesmen thought of bringing Afghanistan under direct political control due to intensified Russian threats. Afghanistan was attacked in 1879, resulting in the Treaty of Gandamak, which was favourable to the British. However, soon, the Afghans rose in revolt and killed the British residents. Even though Kabul was recaptured again, the British returned to the policy of non-interference in Afghanistan’s internal matters.

The Afghan adventure cost the British dearly. They eventually agreed to a boundary solution. In 1893, Mortimer Durand, on behalf of the British, negotiated the Durand line to be the boundary between the Afghan Emirate and the British Indian Empire.

![Swadeshi Movement (1905): Overview, Causes &Amp; Impact [Upsc Notes] | Updated February 1, 2026 Swadeshi Movement (1905): Overview, Causes & Impact [Upsc Notes]](https://99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/swadeshi-movement-featured-66698a5e632b7-768x500.webp)