Annexation of Sindh & Punjab by British- Complete Notes for UPSC

Annexation of Sindh & Punjab by British

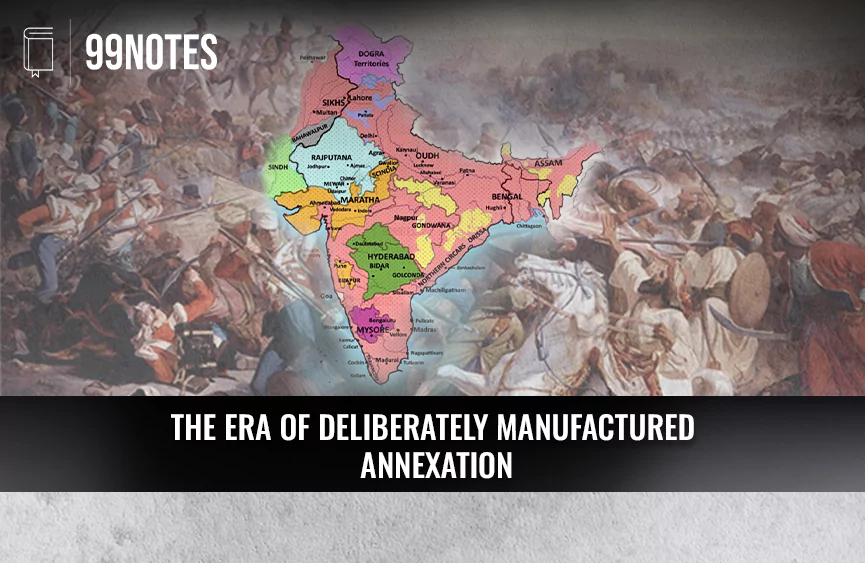

By 1818, the entire Indian subcontinent, except Punjab and Sindh, had been brought under British rule. They directly ruled some states, while in others, the British exercised paramount power. These areas were brought under British control through subsidiary alliance, the Principle of Paramountcy and, in several cases, through outright war.

In some cases, the British also used the principle of diplomacy. For example, the Treaty of Singauli established a boundary between British India and Nepal. This treaty still demarcates the boundary between India and Nepal.

![Annexation Of Sindh &Amp; Punjab By British- Complete Notes For Upsc | Updated March 14, 2026 British Empire In India- 1858 [Deliberately Manufactured Annexations]](https://99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1858-British-empire-of-india.jpg)

William Bentick: Non-aggressive consolidation (1828-35)

- Lord William Bentick’s tenure is known for his policy of non-intervention and non-aggression with Indian states.

- Only Mysore and Coorg were annexed on account of misgovernance.

- He tried to strengthen relationships with the buffer states of Sindh and Punjab in the wake of possible Russian aggression.

- Charter Act of 1833

- The Governor-general of Bengal had now become the Governor-general of India.

- The act paved the way for the centralisation of Administrative, legislative and financial affairs.

- It effectively legalised the British colonisation of India, permitting the English to settle in India.

- William Bentick undertook several administrative and financial reforms. He revised and expanded the Mahalwari revenue administration system, devised by Holt Mackenzie in 1822 in the North West Provinces of Bengal presidency (most of the area is now in modern Uttar Pradesh).

- From 1835, coins bearing the name of Mughal Emperors were stopped. It symbolically declared the establishment of the new dispensation.

- He is credited with several social reforms, such as the abolition of Sati and the suppression of Thugee.

- During his tenure, the westernisation of Indian society and culture started with introducing the English language in the administration and higher education.

Relations with Sindh

- In the 1770s, a Baluch tribe, Talpuras, under Mir Fatah Ali Khan, settled in the region; being excellent soldiers and adapted to the hard life, they soon usurped the power.

- After the death of Mir Fatah, his four brothers (popularly known as Char Yaar) divided the kingdom into themselves and called themselves Amirs of Sindh.

- In 1799, Lord Wellesley tried to revive commercial relations with a hidden aim to counter the brewing alliance of Napoleon, Tipu Sultan and the Kabul Monarch.

- However, in 1800, under the influence of Tipu and other factors, The Amir unceremoniously asked the British agent to leave.

The treaty of ‘Eternal friendship.’

- In 1807, Napoleon and Alexander I of Russia made an ‘alliance of Tilsit’ in which one of the conditions was the combined attack on British India through the land route.

- To create a barrier between British India and Russia, Lord Minto sent Nicholas Smith to make a defensive arrangement.

- In the treaty signed in 1809, both sides agreed to exclude the French from the Sindh and to exchange agents at each other’s court.

The forward policy of Lord Auckland

- Auckland saw Sindh from the perspective of saving British India from a possible Russian invasion and wanted to gain influence over Afghanistan.

- The British saw consolidating their position in Sindh as a prerequisite to their plan in Afghanistan.

- In 1838, due to a possible threat from Ranjit Singh of Punjab, the Amir reluctantly signed a treaty with the British, which allowed the British to intervene in the dispute between the Amirs and the Sikhs and the presence of a British resident. With this treaty, Sindh was turned into a British protectorate.

Anglo-Afghan relations |

The British were alarmed about a possible Russian plan regarding India; hence, they were searching for a “scientific border” (according to the science of military strategy) from the Indian side. Since the passes along the northwest were vulnerable to invasions, they wanted a dispensation in Afghanistan, which was friendly to the British.The forward policy of Lord Auckland aimed to defend the northwest frontier either by signing a treaty with the concerned ruler or by annexing the territory. The tripartite treaty with the English, Ranjit Singh and the Afghan Monarch in 1838 and, later, the annexation of Sindh were consequences of this policy.First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42)

|

Tripartite treaty of 1838: In 1838, they persuaded Ranjit Singh to sign a tripartite treaty between them and the Shah Shuja (deposed ruler of Afghanistan), in which he agreed to British mediation in his disputes with the Amir.

- Shuja Shah of Afghanistan was made to give up his rights in Sindh.

- Subsidiary Alliance: In 1839, They were forced to sign a treaty that allowed the permanent presence of British troops, and the Amir had to pay Rs. Three lakhs annually for maintenance of the troops.

Annexation of Sindh

- The first Anglo-Afghan war was fought on the soil of Sindh. Displeased by the presence of British troops and being asked to pay for their maintenance, they rose in revolt.

- Under Charles Napier, the Amirs were easily defeated and were banished from Sindh.

- In 1843, Governor-General Ellenborough merged Sindh into the British Empire, and Charles Napier was made its governor.

- The annexation of Sindh is criticised because the causes were deliberately manufactured.

Annexation of Punjab

After the execution of Guru Govind Singh, the Sikhs under Banda Bahadur Singh revolted against the Mughal Empire during the rule of Bahadur Shah. Following a stiff resistance, Banda Bahadur Singh was defeated and executed by Farrukhsiyar in 1716. His death made the Sikh leadership, and they got divided into two groups, Bandai (liberal) and Tat Khalsa (orthodox).

Two factors lead to the emergence of Sikh power in the Punjab region:

- Sikhs organised themselves into Dal Khalsa which included all the sikh fighting bands.

- Ahmad Shah Abdali’s invasions weakened the Mughal Empire‘s control over the region. There was utter lawlessness during this time, and many fighting bands struggled for control. This allowed Dal Khalsa to consolidate further.

Dal Khalsa

In the 18th century, Sikhs organised themselves into several Bands (Jatthas) and later Misls. Initially, it was not much organised, even though all the Bands attended the formal Sarbat Khalsa (All of Khalsa) whenever the meeting was called. Gurumata (The Guru’s decision) was passed in such meetings, which were binding on all Sikhs.

The Rakhi System: Till the 1750s, the Punjab region was under Maratha control, and a Chauth was levied. It ensured civil administration and soldiers were deployed. But in the age of lawlessness, there needed to be a guarantee of protection against foreign invaders and bandits. Thus, the Rakhi taxation system also came into being through the pronouncements of the Sarbat Khalsa, i.e. Gurumatas. It offered protection to cultivators on payment of tax equivalent to 20% of the produce.

From 1763 to 1773, with the introduction of taxation, many Misls (meaning state, in Arabic) emerged in the Punjab region under Sikh chieftains. It was a military brotherhood. The central administration of a Misl was based on ‘Gurumatta Sangh‘, a political, social and military system. They were able to put successful resistance to Mughal governors first and then to Ahmad Shah Abdali, who seized the rich province of Punjab and the Sarkar of Sirhind from the Mughals. The Sikhs declared sovereign rule by striking their coin (Nanak-Shahi and Gobind-Shahi coins) in 1765.

In 1784, the Sikhs were further organised by Kapur Singh Faizullapuria under Dal Khalsa, which was a combined force that included all Jatthas and Misls. It had two sections: Budha Dal, the army of the veterans and Taruna Dal, the army of the young.

The entire Dal Khalsa body used to meet at Amritsar during Baisakhi and Diwali and took collective “Resolutions of the Gurus”, known as Gurmathas.

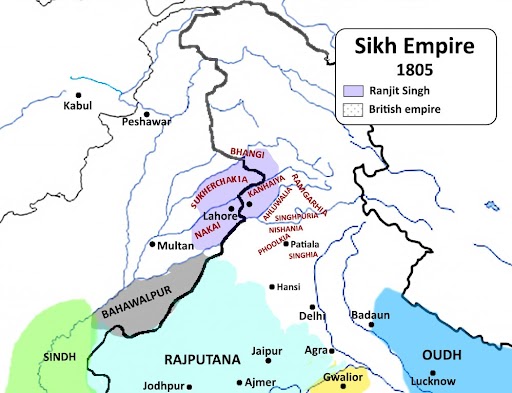

The Sikh Empire

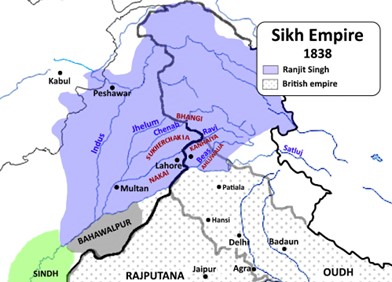

In the late 18th century, Sikh territories extended from Indus to Jamuna. The next significant Sikh expansion took place under the leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who reunited these groups and established the Sikh empire with its capital at Lahore.

Ranjit Singh’s rise: He was the leader of Sukarchakiya Misl, who succeeded his father, Mahan Singh, at the mere age of 12. He took advantage of the prevailing political situation in the region and Afghanistan and established an Empire in Central Punjab. He Adopted the following strategy:

- Maritorial Alliance: In 1796, he entered into a maritorial alliance with Kanhaiya Misl and with Naiki Misl in 1797. His favourite wife, Datar Kaur, belonged to Naiki Misl.

- Military Alliances: In 1798, with the alliance of Naiki Misl, Ranjit Singh defeated Afghans, first in the Battle of Amritsar and then in the streets of Lahore.

- Diplomacy: For example, In 1800, the ruler of Jammu ceded control to Ranjit Singh.

- Spectacle: He crowned himself as the King of Punjab in 1801; Prayers were held in mosques, gurudwaras and temples. He issued Nanak-Shahi coins on this occasion.

- Military Campaigns: The joint forces of Kanhaiya Misl defeated the Bhangi Misl, who surrounded Lahore in 1799 and captured Amritsar from them.

With the acquisition of Jammu and Amritsar, both the political (Lahore) and the religious (Amritsar) capitals of Punjab came under Ranjit Singh.

Relations with the British

In the wake of the possible threat of a combined French-Russian attack on India through the land route, Lord Minto sent Charles Metcalfe to Lahore in 1807; however, the negotiations failed.

Treaty of Amritsar:

In 1809, Ranjit Singh agreed to sign the Treaty of Amritsar with the British.

- He accepted river Sutlej as the boundary between his and the Company’s territory. This checked his ambition to control the entire Sikh nation.

- In 1813, Attock was captured under his dewan Mokham Chand’s leadership.

- Now, he expanded his territories towards the west and captured Multan (1818), Kashmir (1819) and Peshawar (1834).

Tripartite Treaty:

Due to the compelling political situation, he signed the Tripartite treaty with the British. It forced Ranjit Singh to recognise Shah Shuja (a disposed king who had lived in Ludhiana since 1809) as the king of Afghanistan. Shah Shuja signed on the following terms:

- Shah Shuja would be crowned in Afghanistan & would conduct foreign affairs on the advice of Sikhs & British;

- He would give up sovereign rights over Sindh in exchange for money.

- He would recognise the Sikh ruler – Ranjit Singh’s claim in the east of Indus.

However, Ranjit Singh didn’t allow passage to the British army through his territories to attack Dost Muhammad, the Afghan Amir.

The tripartite treaty helped the British to manage the threat emanating from Afghanistan. It gave the British an upper hand in Sindh as it became a British protectorate first and was later annexed by the British.

Joint Attacks on Afghanistan: Ranjit Singh and the British attacked Afghanistan from the South and Khyber Pass, respectively, and helped Shah Shuja in defeating Dost Mohammad Khan.

The first Anglo-Sikh War (1845-46)

Due to the tripartite treaty, the bonhomie subsided as soon as Ranjit Singh died.

Causes of the 1st Anglo-Sikh War:

- Anarchy after Ranjit Singh’s death: Ranjit Singh died in 1839. Within a few months, his son and his grandson, too, passed away. This created a situation of anarchy in the Empire. Daleep Singh, a minor son of Ranjit Singh, ascended the throne with Rani Jindan as regent.

- The increasing number of British troops near the border of the Empire.

- The British campaign in Afghanistan and the annexation of Gwalior and Sindh in 1841 created suspicion among the Sikhs.

- The Sikh army crossing the river Sutlej was seen as a provocation and became the immediate cause of war.

Due to the treachery of its commanders, the Sikh army conceded a decisive defeat and had to sign the humiliating treaty of Lahore. Terms of the treaty:

- War indemnity of 1 crore to the British.

- The Jalandhar doab was annexed to the Company’s dominion.

- Posting of a British resident in Lahore under Henry Lawrence.

- Daleep Singh ascended the throne under Rani Jindan as regent

- Under the treaty of Bhairowal, Rani Jindan was removed as regent, and a council of regency was set up.

Further, a treaty of Amritsar was signed:

- Gulab Singh was recognised as the Maharaja of Jammu, and his territories were restored. He was the Raja of Jammu, even under the Sikh empire, but acted in British interest in the Anglo-Sikh war.

- He agreed to take subsidiary British forces and also promised his own forces for the British cause.

- Kashmir was sold to Gulab Singh for 75 Lakh Nanakshahi Rupee coins from the Sikhs. The Sikhs used this payment to pay the entire war indemnity to the British.

The Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-49)

Causes of the 2nd Anglo-Sikh War:

- The Sikhs felt humiliated by the defeat in the first Anglo-Sikh war and the treaties signed after the defeat.

- The inhumane treatment of Rani Jindan, who was pensioned off to Banaras, added to the resentment.

- Mulraj, the governor of Multan, was replaced by a new governor. However, he revolted and murdered two British officers. This became the immediate cause of the war.

- The then Governor-General Lord Dalhousie, a staunch expansionist, got the pretext to annex Punjab.

Lord Dalhousie himself proceeded to Punjab. Three important battles were fought during the war:

- The battle of Ramnagar was indecisive.

- The Sikhs won the battle of Chillhanwala.

- Battle of Gujarat (a small town on the banks of Jhelum): the Sikh army lost the war and surrendered.

Finally, Punjab was annexed. After the end of this war, all of India, including today’s Ladakh and Jammu-Kashmir, came into the British domain.

Lord Dalhousie (1848-56): Doctrine of Lapse

Dalhousie was a staunch expansionist. During his tenure, Punjab was annexed in 1849. He annexed the state of Oudh on the pretext of misgovernance.

He is known for implementing the doctrine of lapse, which led to the annexation of several Indian states. During his reign, the expansion of the British Empire was nearly completed.

The Doctrine of Lapse

- It was an annexation policy in which the adopted son could inherit only the private property of his foster father and not the state. It was up to the Paramount power whether to accept the inherited son as the rightful successor or not.

- Although Lord Dalhousie did not invent the doctrine, he extensively used it to expand the British Empire. It was also a coincidence that during his tenure, many of the rulers of Indian states died without a male heir.

- Eight states were annexed during his tenure; some of the important states were Satara (1848), Jhansi (1853), and Nagpur (1854). Other smaller states were Jaitpur (Bundelkhand), Sambalpur (Orissa), and Baghat (Madhya Pradesh).

- Awadh was also annexed in 1856 under this doctrine, not because of the absence of a male heir but because of internal misrule in the state.

- The annexations became one of the reasons for the revolt of 1857.

| States | Year of Annexation |

| Satara | 1848 |

| Jaipur | 1849 |

| Sambalpur | 1849 |

| Baghat | 1850 |

| Udaipur | 1852 |

| Jhansi | 1854 |

| Nagpur | 1854 |

British Conquest: Accidental or Intentional

There are various scholarly opinions regarding the nature of the British expansion in India:

The Accidental Expansion view:

- One group of scholars, led by John Seeley, argued that the British conquest of India was unintentional. According to them, the British came for trade purposes and had no desire to acquire territories.

- They argue that the English were unwillingly drawn into the internal politics of the Indian states.

The Intentional Expansion view:

- The other group argues that the British came with a clear intention of colonising the country and worked towards that direction.

- They dismiss the claim that the British observed political neutrality in its early days.

Both arguments have some merits. The British initially came for lucrative trade opportunities in India. Gradually, they started acquiring territories to protect their trade interests.

In this process, they realised how disunited the political situation was. Ambitious politicians and administrators like Lord Wellesley and Lord Dalhousie utilised the situation, and they worked towards a clear goal of establishing an empire.

Economic Impacts of British Policies

Textile Industry and Trade

The collapse of the Indian textile Industry was facilitated by two factors:

- Indian textiles had a big market in Europe, but with the coming Industrialisation in England, the direction of trade reversed, and India became an importer of British-made goods.

- The British imposed export duties on the Indian goods while the British imports enjoyed duty-free access.

Thus, India became a net importer of finished textiles and a net exporter of raw materials. This led to the virtual collapse of the Indian weaving industry, and the weavers migrated to rural areas to work as agricultural labourers, increasing the burden on the rural economy.

The uneven competition faced by the Indian weavers was called de-industrialisation by the national leaders. The British aimed to transform India into a consumer of British goods. Indian goods could not compete with British machine-made goods.

Land revenue policy and Land settlements (detailed description in ‘Revenue settlements during the British rule’.

The British undertook several land revenue experiments, which caused hardship to cultivators.

Commercialization of Agriculture

The British introduced many commercial crops such as Tea, Coffee, Indigo, Opium, Cotton, Jute, Sugarcane and Oilseed.

- The commercialisation of agriculture further expedited the transfer of land ownership, thereby increasing the number of landless labourers.

- Forced commercialisation of subsistence farmers also caused a decrease in food production, which often led to famine. For example, Indigo farmers in Bengal and Bihar were compelled to grow Indigo on the 3/20th part of their land to export to the European markets. Nil Darpan, a Bengali Novel written by Dinabandhu Mitra in 1858-59, shows the plight of these farmers, who revolted in 1859 (commonly known as Indigo Revolt/Nil Vidroh).

In Plantations: The workers faced severe hardships in plantations. For example, workers of tea plantations in Assam were brought from the tribal regions of central India. They were not allowed to leave their plantations. This also led to drastic demographic changes in India.

Rise of moneylenders

Excessive and time-bound demand for revenue by the British government forced the peasants to take money from moneylenders.

- In the Ijaradari system (Permanent Settlement), introduced by Cornwallis, the revenue demand was fixed, regardless of the produce.

- They often exploited the farmers by charging high interests and false accounting.

- Upon failure of payment, the land was confiscated.

Gradually, their land was passed on to the moneylender class.

The new middle-class

With the rise of British commercial interests, new opportunities opened to a small section of the Indian people. These included:

- Agents and intermediaries of the British traders who made huge gains.

- The new landed aristocracy came into being after Permanent Settlement.

- The introduction of new administrative institutions created job opportunities for the English-educated class, who got patronage from their Masters.

Transport and Communication

The introduction of Railways opened an avenue for British bankers and investors to invest surplus wealth and materials in the construction of railways. Railways benefited the British capitalists in two crucial ways:

- It made trading in commodities much easier and more profitable by connecting the internal markets with the ports.

- The rail engines, coaches and the capital input for building rail lines came from Britain.

Though it was set up for the advantage of the British, it eventually played an essential role in the national awakening by becoming a medium of communication for the nationalists of different regions.

Telegraph lines across India were built during Dalhousie’s period.

Socio-Cultural Impact

During the 18th and 19th centuries, Indian society had become stagnant, and many social practices like rigid caste system, child marriage, female infanticide, Sati, and Polygamy prevailed.

- Penetration of Democratic ideals: Due to the spread of English education, many new ideas such as Equality, Liberty and rights came into India. These ideas appealed to a section of our society and led to several reform movements in different parts of the country.

- Social reforms: Such as a ban on the practice of Sati and allowing widow remarriage.

- Rule of Law: A formal criminal was introduced by the Britishers. Indian Penal Code was drafted in 1834 under the chairmanship of Macaulay. It was implemented in 1862.

Most of the British administrators treated Indian knowledge as inferior to Western knowledge. However, they were cautious and did not attempt rapid modernisation of India due to fear of reaction among people.