Land Revenue System in British India- UPSC Modern History Notes

Land Revenue System in British India

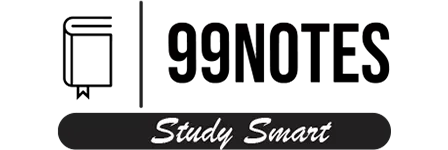

Land revenue settlement refers to the system in which land tax revenue is agreed between the owner of the occupied land or any other assigned leader and government. The government collects tax revenue directly from cultivators (Ryotwari) or indirectly through an appointed representative (Permanent settlement).

Early revenue settlement under British Rule

Background

- The company got Diwani rights of Bihar, Bengal and Orissa in 1765 (Treaty of Allahabad) under Robert Clive.

- British started to finance its trade through these revenue collections. Earlier, to buy Indian goods for trading, they imported gold and silver from Britain.

Features of Early Land Revenue System in British India

- They had retained the basic administration established by the Nawabs of Bengal.

- The Zamindars were recognised as the land owners.

- The main revenue collector of the Company was Naib (deputy) Dewan, who collected the revenue on behalf of the company.

Shortcomings

- It led to corruption and continual interference of the company’s servants in the administration.

- This disorganised revenue settlement was one of many reasons for the Bengal famine of 1769-70.

The Izaredari system/The Temporary settlement (1773)

Background

- The administration and revenue settlement during Clive led to lawlessness and corruption among officials.

- Warrant Hastings (1772-1785) abolished the revenue settlement during the Robert Clive.

- In 1773, he introduced the Izaredari system in Bengal and took direct charge of Diwani rights.

Features

- The government were recognised as land owners.

- The right to collect revenue from an area was auctioned for a particular time.

- The highest bidder was called Izaredar, who offered to pay the largest amount to the company.

Shortcomings

- As it was based on speculative profit making, the auction rates were unrealistically high, leading to the peasants’ oppression.

- The rates were not uniform, which led to the instability of food prices.

- Moreover, the revenue collections fluctuated widely, causing financial uncertainties in the administration.

- This system also led to corruption, such as profitable contracts on very easy terms being given to the friends and ‘benamidars’ of men in power, leading to loss to the company.

- The sole purpose of the settlement act was revenue maximisation; thus, there was little consideration for the investment in land.

Permanent settlement/zamindari system (1793)

Background

- The Izaredari system led to the decline in agriculture, further leading to the handicrafts’ deterioration.

- Moreover, the company could not get the surplus revenue it wanted for buying Indian goods.

- The company officials and then governor of Bengal, Lord Cornwallis (1786-93), believed that the settlement system’s uncertain and arbitrary character had led to corruption and oppression.

- Lord Cornwallis introduced Permanent settlement in 1793.

- Zamindars were made buffers between the state and the people.

- The rates were fixed permanently with the expectation of –

- Stable revenue for the states.

- Reduction in corruption that existed when officials could alter the assessment at will.

- Investment by the zamindar in improving the land productivity if the production is increased.

Features

- Permanent settlement was first introduced in Bengal and extended to Odisha, North Madras and Varanasi.

- The revenue rates were fixed permanently.

- The zamindars were recognised as the land owners and collectors of revenue from the cultivators who had now become tenants (the ryots or raiyyats).

- Rajas and Taluqdars were recognised as zamindars.

- They had inheritable rights over the land and could sell, mortgage or transfer it.

- New additions to the Permanent settlement system –

- Revenue sale law or sunset law of 1793 – If zamindar failed to pay the revenue regularly, the government sold his land in the auction to recover dues, and all the rights would be vested in the new owner.

- Additional regulations were added in 1793, 1799, and 1812 –The Zamindar were now empowered to seize the tenants’ property if the rent had not been paid, without any court of law permission.

Shortcomings

- Position of Zamindars –

- Rates were fixed very high and had no provision for relaxation in times of flood, drought, or other calamities. Non-payment led to the takeover of the Zamindari rights. Around half of Zamindari’s rights were sold between 1794 and 1807.

- Subinfeudation – Due to the high rate, many zamindars divided their estates into small lots of land called patni taluq. Then, they rented them out permanently to holders (patnidar) on the promise that they would pay a fixed rent.

- Position of Cultivators –

- Zamindars lived lives of luxury at the expense of their tenants and did nothing to improve the condition of the land.

- The cultivators were harassed and exploited by the zamindars. No written agreements (pattas) between the zamindar and cultivators were made.

- High rent drove the cultivators into the hands of the moneylenders.

Need for a new settlement system

- Fixed rent charges left no scope for increasing the revenue for the British, who needed it to fund its wars.

- So, the officials started to think of ways to increase the government’s revenue through a new system.

The Ryotwari System (1820)

Background

- Two officers, Thomas Munro and Alexander Read, were sent to administer a newly conquered region of Madras in 1792.

- The region had no traditional Zamindars.

- They experimented with revenue collection by directly collecting revenues from the villages instead of the Zamindars.

- They proceeded with assessing each cultivator or ryots Thus, its evolved version was named the Ryotwari system.

- This early Ryotwari was a field assessment system,e., the tax payable on each field was fixed by a government official after assessing it. Then the cultivator had the choice of cultivating that field and paying that amount or not cultivating it. If no Other cultivator could be found, then the area would not be cultivated: it would lie fallow.

Features

- Ryotwari system was introduced by Thomas Munro in Madras in 1820 when he was appointed as Governor of Madras.

- It was also expanded to Gujarat under the Bombay presidency, the newly conquered Peshwa’s territory, Berar, East Bengal, parts of Assam, and Coorg.

- Ryots were recognised as land owners and were free to transfer, sublet or sell their land.

- Ryots paid the revenue directly to the company without any intermediaries.

- Based on an estimated land production, the tax rate to be paid was 45% to 55%.

- The settlement was revised periodically and thus was not permanent.

- Although, in theory, the ryots were free to cultivate the land of their choice, they were essentially coerced into doing so, even if they didn’t want to.

- Land could be seized if the revenue was not paid.

- The ‘putcut’ assessment – The land was not surveyed in many areas under the Ryotwari system. Tax rates were fixed arbitrarily, often based on the payments in earlier years.

Significance

- It resulted in larger revenue for the government than any other system could have produced as there were no intermediaries. Whatever surplus was produced directly went to the government.

- The actual cultivating peasants were recorded as the occupants or ‘ryots’ and thus secured the title to their holdings.

Shortcomings

- Overassessment of land – The land revenue fixed was often greater than land capacity.

- Rigid collection – Collection methods were strict, often involving torture to extract taxes. The Madras Torture Commission Report of 1855 revealed the practices of bribery, corruption and coercion by the subordinate officials of the collectorate.

- Corruption – The officers could be bribed while assessing land, which led to corruption.

- Rise in inequality – As there was no limit on the amount of land a ryot could hold, there was a great difference between the status and wealth of the ryots.

- Landlords who did not cultivate their land could register as owners, reducing cultivators to tenants, servants, or bonded labourers.

- The high tax and the harassment in collection devalued land value as not many wanted to buy it.

The Mahalwari System (1822)

Background

- Between 1801 and 1806, the British had a sizeable territorial gain in North India (North-Western Provinces) due to the aggressive policies of Lord Wellesley.

- There was an increase in the demand for revenue.

- With such increased demand, there was resistance from big Zamindars and Rajas, who the new administration later evicted.

- Thus, it was becoming necessary for the government to collect the revenue directly from the village.

- The government’s expenditure continued to exceed its revenue, so the idea of a permanent settlement was dropped.

Features

- Mahalwari system was a recommendation of Holt Mackenzie. It was formalised by the Regulation VII of 1822.

- Mahal was a revenue estate comprised of a village or a group of villages. Revenue was assessed based on the produce of a mahal, and it was considered the basic unit for the payment of land revenue.

- The revenue was revised periodically, not permanently fixed.

- The village community was recognised as the owner of the land. However, individual ownership rights lay with the cultivator.

- The responsibility for collecting and paying that tax to the Company government lay with the village headman (called lambardar) or a community of village leaders.

- It was implemented in parts of Uttar Pradesh, the North Western province, Central India and Punjab.

- In the North Western Provinces, it was known as ‘mauzawar’, and in the region of the Central Provinces, its name was ‘malguzari’.

Significance

- This system had some features of both the Zamindari and the Ryotwari systems.

- It required the government officials to record all the rights of cultivators, zamindars, and others on every piece of land.

- Areas under the Taluqdars’ control were reduced.

- The officers made a direct settlement with the village headmen and supported them in the court against the Taluqdars.

Shortcomings

- It was impossible to record the rights on every piece of land.

- The officials’ assessments were often based on guesswork and remained on the higher side to increase revenue collection.

- Due to higher tax imposition, the debt on cultivators increased.

- Eventually, the lands went to the moneylenders and merchants.

- Cultivators were either ousted from their land or were made to turn into tenants.

- Moreover, finding a new land buyer was challenging as the tax rate was higher.

- The Mahalwari system brought impoverishment and widespread dispossession to the cultivating communities of North India. Their resentment led to the popular peasant uprisings of the 19th century.

The Production of Plantation crops (Indigo)

Plantation crops refer to commercial crops that are grown on an extensive scale.

Background

- Britishers used India for the raw material for Europe.

- By the 19th century, they started to force or persuade cultivators in India to grow the crops that Europe required. Examples are Jute in Bengal, Tea in Assam, Sugarcane in United provinces (UP), Wheat in Punjab, Cotton in Maharashtra and Punjab, and Rice in Madras.

- Indigo was one such plantation crop.

- Indigo is a tropical plant used in the dying industry for its blue

- The supply of Indigo in Europe was fulfilled from West Indies and America

- But between 1783 and 1789, indigo production in the world fell by half.

- Faced with rising demand, the Britishers turned to India to expand the area under indigo cultivation.

- Two main systems of indigo cultivation were adopted nij and ryoti.

Nij

- Features –

- In this system, the planter produced the indigo in the directly controlled lands.

- The land was either bought or rented from other zamindars.

- Labours were hired and employed directly.

- Shortcomings of Nij Cultivation –

- It wasn’t easy to get extensive areas for cultivation.

- The indigo can only be grown on fertile lands that are already densely populated.

- Moreover, a large human resource was required, especially when peasants were busy with their rice cultivation.

- Buying and maintaining ploughs and bullocks were a big problem as around one Bigha of Indigo cultivation required two ploughs.

- Thus, as a result, till the late 19th century, less than 25 per cent of land producing indigo was under nij cultivation, and the rest was under the ryoti system.

Ryots

- Features –

- Under this system, the planters forced the ryots or the village headmen on behalf of the ryots to sign an agreement/contract called

- Under this agreement –

- The ryots got cash advances from the planters at low-interest rates.

- They had to grow the indigo on at least 25 per cent of the area under cultivation.

- Planters provided them with the seed and the drill while the ryots prepared the soil, sowed the seeds and looked after the crop.

- After the end of one production cycle and the crops’ delivery, a new loan was given to the ryots.

- Shortcomings of Ryoti Cultivation –

- Ryots got low prices for the indigo, and the cycle of loans never ended.

- The planters forced them to grow indigo on the most fertile soil. The peasants preferred these soils for rice cultivation. But unfortunately, the Indigo plant’s deep roots exhausted the fertility of the soil.

- A ryot was not able to end the loan cycle.