Partition of India: Summary, Cause, and Impact- Complete Notes for UPSC

In July 1946, the Muslim League withdrew from accepting the Cabinet mission plan in response to Nehru’s statement and called for “direct action” on 16 August to achieve its goals for Pakistan. In this chapter, we will discuss the emergence of communalism and its culmination with the partition of India and the formation of Pakistan.

What is communalism?

Communalism is an idea or belief that all those who share a common religion also have similar social, cultural, political, and economic identities and interests. In other words, it is the notion that religion serves as the base of society and a basic unit of division in society.

Communalism in India has evolved through three broad stages.

- Communal Nationalism: The interests of all religious community members were the same; for example, it was argued that a Hindu Zamindar and a peasant had common interests because both were Hindus.

- Liberal Communalism: If two communities have different religious interests, their interests will also differ in the secular sphere (economic and political).

- Extreme Communalism: As per this notion, not only do interests differ, but they are also antagonistic and conflicting. It meant that Hindus and Muslims could not co-exist peacefully. The two-nation theory was based on this notion.

Factors contributing to the growth of communalism in India

Communal trends increased with the British policies in India. To maintain their rule, they adopted a divide-and-rule policy that wedged the divide between Hindus and Muslims. The following factors led to the growth of communalism in India:

Socio-economic factors:

- British imperial rule brought about significant changes in the power structure of Indian society. It resulted in the decline in the power of the upper-class Muslims, particularly in Bengal, where they lost their semi-monopoly status in employment in the upper positions of army, administration and judiciary. Soon, they were also evicted from their dominant land-holding.

- Compared to Hindus, Muslims were lagging in adopting English education, new professions and posts in the administration.

- There was a lack of industrial development, causing acute unemployment and cutthroat competition for existing jobs.

- These circumstances led to a feeling of insecurity among the Muslims.

British policies

- British policies were one of India’s biggest factors in the growth of communalism. However, it must be noted that the British did not create communalism; they took advantage of the existing socio-economic and cultural differences to serve their political ends.

- Initially, the British saw Muslims with suspicion, particularly after the revolt of 1857 and 1857 revolts and were subjected to discrimination and repression. However, after the emergence of Indian nationalism, the government reversed its policy and tried to rally the Muslims behind it through concessions and reservations (Bengal partition, separate electorate, etc.).

- Imperialist historians also played their part by interpreting history through the communal lens. They portrayed the mediaeval period as Muslim and the ancient period as Hindu.

Socio-religious Movements

- Muslim revivalist movements like the Wahabi and Deobandi Movement and the Shuddhi movement by Arya Samaj had communal overtones, which also played a role in the growth of communalism.

National Movement

- Initially, the Congress did not take up socio-religious questions in its forums, but after the advent of militant nationalism, religious symbols such as Tilak’s Ganapati and Shivaji festivals, anti-cow slaughter campaigns, invocation of Gods and Goddesses in oaths etc., began to be used which created suspicion among the minorities.

- Lucknow Pact and Khilafat agitations provided legitimacy and encouragement to the communal elements.

Evolution of the Two-Nation Theory

The nation theory is a religious-nationalist ideology that justifies India’s partition on the grounds that Indian Hindus and Indian Muslims are two separate nations with their own customs and traditions. This theory was initially propounded by Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and later promoted by Mohammad Ali Jinnah.

The development of the two-nation theory progressed as follows:

- 1887: Syed Ahmed Khan, believing that Muslims’ share in administrative posts and in the profession could be increased only by showing loyalty towards the British, decided to oppose the national movement under the Indian National Congress.

- 1906: In 1906, Muslim leader Aga Khan led a Muslim delegation (Shimla delegation) to the Viceroy, Lord Minto, to demand a separate electorate. The same year, the Muslim League was founded by the Aga Khan, Nawab Salimullah of Dacca, and Nawab Mohsin-ul-Mulk to raise the slogan of separate Muslim interests and keep the Muslim intellectuals away from the Congress.

- 1909: A separate electorate was awarded to Muslims under the Morley-Minto reforms.

- 1915: Formation of All India Hindu Mahasabha by the Maharaja of Kasim Bazar to advocate the interests of orthodox Hindus.

- 1916: Under the Lucknow Pact, the Congress accepted a separate electorate for Muslims. The pact gave political legitimacy to the existence of the Muslim League.

- 1920-22: Even though the Khilafat-Non-cooperation movement witnessed Hindu-Muslim unity, the agitation is said to have further communalised the national movement.

- 1920s: This period saw the growth of communalism not just in the political sphere but also at the societal level. The Arya Samajists started the Shuddhi (Purification) Movement to reconvert those who had converted to Islam. In retaliation, the Muslims organised the Tablighi movement. The leaders of the national movement were also divided into communal movements, and many of them joined the Hindu Mahasabha. The Ali brothers, one of the leaders of the Khilafat-Non-Cooperation movement, accused the Congress of protecting only Hindu interests.

- 1925: Formation of Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh with a focus on Hindu Rennaisance and revitalisation of the Indian value system.

- 1928: The Nehru report on constitutional reforms was opposed by the Muslim hardliners and Sikh League. Jinnah proposed 14 points, in which he demanded a separate electorate and reservations in government services for Muslims.

- 1930-34: Except for Jamaat-i-ulema-i-Hind, the state of Kashmir and Khudai Khidmatgar, the overall participation of Muslims in the Civil Disobedience Movement was very low as compared to the Khilafat agitations. While the Congress stayed away from the round table conferences, the communalists attended all of them.

- 1932: The British government bolstered the Muslim communalists by announcing the communal award, which accepted almost all the demands put forward by Jinnah’s 14 points.

Post-1937:

- After the poor performance in the 1937 provincial elections, the League decided to resort to extreme communalism, and it also began to acquire a mass character.

- Now, instead of projecting Muslims as minorities, the Muslim communalists started to project them as separate nations.

- The idea of Muslims as a separate nation was developed in the early 1930s by Muslim intellectuals like Rahmat Ali and Poet Muhammad Iqbal.

- In response, Hindu nationalist organisations like RSS and Hindu Mahasabha also adopted strong positions.

- The Muslim League started a strong campaign against the Congress ministries. It also demanded that the Congress should declare itself as a representative of Hindus only.

League’s Demands for Pakistan

- At the Lahore session in the 1940 Muslim League, Jinnah came up with the two-nation theory, according to which Muslims were not a minority but a nation as they were different people economically, politically, socially, culturally and historically.

- The ‘Pakistan resolution‘ passed in the Lahore session called for the “grouping of all geographically contiguous Muslim majority areas”.

Responses to the League’s demands

Some individuals made efforts to solve the political deadlock between the Congress and the League as follows:

· Rajagopalachari Formula (1944)

C Rajagopalachari was a veteran Congress leader who devised a plan for Congress-League cooperation. The plan had the backing of Mahatma Gandhi, and it became the basis for the Gandhi-Jinnah talks. The main points of the plan were:

- Muslim League will cooperate with the Congress in forming a provisional government at the centre.

- League to endorse Congress’ demand for independence.

- After the war, the entire population of Muslim-majority areas in North-West and North-East India was to decide by a plebiscite (not just Muslims) whether or not to form a separate state.

- In the event of acceptance of partition, an agreement was to be made for jointly safeguarding defence, commerce, communications, etc.

- The above conditions would apply only when Britain transferred full powers to India.

Response to the Rajagopalachari Formula:

- Many Congress leaders were not in favour of the plan.

- Hindu leaders led by VD Savarkar condemned the plan.

- Jinnah wanted only the Muslims of the North-West region and North-East region to vote in the plebiscite, and he rejected the idea of entire population participation. He also opposed the idea of a common centre. Hence, the plan failed.

· Desai-Liaqat Pact

Bhulabhai Desai, leader of the Congress in the Central Legislative Assembly and Liaqat Ali, the deputy leader of the Muslim League, came up with a draft proposal for the formation of an interim government at the centre. This pact included the following plan:

- As per the plan, (i) an equal number of persons will be nominated by the Congress and the League in the Central Executive (They need not be from the Central Legislature), and (ii) 20% of them will be minorities.

- Liaqat Ali gave up the demand for a separate state in favour of parity between Hindus and Muslims in the council of ministers.

However, No settlement could be reached as the proposals were not endorsed by either the Congress or the League.

Communal riots (Direct action) and the formation of the Interim government

After League’s withdrawal from the Cabinet Mission plan, it gave a call for “direct action” to achieve its goal. The aftermath of the direct action is as follows:

- The call for direct action led to communal riots, first in Calcutta and then spread over other areas of the country, particularly in Bombay, eastern Bengal and Bihar, some parts of the UP, NWFP and Punjab.

- Encouraged by the Prime minister of Bengal, Suhrawardy, the League hooligans resorted to large-scale violence against the non-Muslims.

- After the element of surprise was over, the Hindus and Sikhs also hit back.

- The riots that began continued till the early part of 1948, killing and injuring several lakhs of people, wreaking havoc on private property, and defiling countless religious sites.

Interim Government

Despite differences between the Congress and the League, the government went ahead with the formation of an interim government since there was an impending threat of mass upsurge and worsening law and order situation.

- Despite the title, it was not a government with a cabinet but rather an advisory body to the Viceroy’s executive council.

- The interim government was formed on 2 September 1946 under the leadership of Jawahar Lal Nehru.

- The government was not able to effectively control the law-and-order situations due to a lack of support from the British commander-in-chief. The veto power of the Viceroy was also an impediment to the functioning of the government.

- The situation worsened when the Viceroy Wavell persuaded the League to join the government on 26 October 1946 despite persistence on direct action and rejection of the Cabinet Mission Plan in the hope that it would adopt a moderation stance.

- Now, the functioning of the government was frequently obstructed and divided along the Congress and the League camps. Liaqat Ali, the finance minister, restricted the effective functioning of the government. For the League, the interim government was another front of the continuing civil war.

- Finally, in February 1947, the nine interim government members demanded that the League members resign.

- The Muslim League demanded the dissolution of the constituent assembly despite the government’s assurance that the League’s interpretation of the grouping was the correct one.

| Council of Ministers in the Interim Government | |

| Jawahar Lal Nehru | Vice-president of the executive council, External Affairs and Common Wealth relations. |

| Vallabhbhai Patel | Home, Information and Broadcasting |

| Baldev Singh | Defence |

| Dr John Mathai | Industries and Supplies |

| C Rajagopalachari | Education |

| Rajendra Prasad | Agriculture and Food |

| Liaqat Ali Khan (Muslim League) | Finance |

| Jogendranath Mandal (Muslim League) | Law |

Atlee’s statement of February 1947

To defuse the ongoing crisis, Clement Atlee, the British Prime minister, made an announcement in the British parliament regarding the British intention to leave the Indian subcontinent. The main points of his announcements were:

- It fixed the date for the British withdrawal from India as 30 June 1948.

- An announcement of the appointment of the new Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, was made.

- British power and obligation towards the princely states would lapse, but it would not be transferred to any successor governments in British India.

- The British would transfer power to the central government, but if the constituent assembly was not fully representative, i.e., if the provinces with a Muslim majority did not join, the British would transfer the power to the existing provincial governments.

- The announcement had a clear hint of the partition and even the fragmentation of the country into numerous states.

Response to Atlee’s statement

- The Congress agreed to the transfer of power to more than one centre as it meant that the existing assemblies could frame a constitution for the area represented by them, and it could be a way out of the existing deadlock.

- Emboldened by the government’s stand, the League launched a civil disobedience movement to defeat the coalition government in Punjab led by the Unionist Party under Khizr Hayat Khan.

Evaluation of Atlee’s statement

- The British wanted to appear sincere in their promise to grant self-government.

- The government hoped that a fixed date would pace up the resolution of the constitutional crisis.

- The government had realised that there had been an irreversible decline in the government authority.

Independence and Partition

- Large-scale communal violence and obstruction by the League in the interim government convinced the Congress leaders that perhaps there was no alternative to the partition of India.

- After the League’s overthrow of the Unionist government in Punjab, the Hindu and Sikh minorities picked up the demand for partition of the province.

- In March 1947, the Congress working committee passed a resolution pointing out that the province of Punjab and Bengal would be partitioned if the country was partitioned.

Mountbatten, the new Viceroy

- He was sent to explore the possibility of division and unity and the form of transfer of power. He was informally given more power to speed up the decision-making.

- In the initial months after coming to India, Mountbatten tried to build consensus among parties. However, Jinnah’s stubbornness made him realise that partition was inevitable.

Mountbatten Plan, June 3, 1947

Under this plan, the British government agreed to the partition of India and that the successive governments would be given dominion status. The main points of the plan were:

- The plan advanced the date of withdrawal to 15 August 1947.

- The princely states were given the option to join either India or Pakistan, and their independence was ruled out.

- A boundary commission was to be set up if the partition was to take place.

- As per the plan, the Punjab and Bengal Legislative assemblies would meet in two groups, Hindus and Muslims, to vote for partition. These provinces would be partitioned if a simple majority of either Hindus or Muslims group voted in favour of partition.

- Sindh was allowed to take its own decision.

- The fate of NWFP and Sylhet in Assam was to be decided by referendum.

Implementation of Mountbatten Plan

- The legislative assemblies of Bengal and Punjab voted in favour of the partition of these two provinces. Consequently, East Bengal and West Punjab joined Pakistan.

- Two boundary commissions were constituted to demarcate the boundaries of partitioned provinces.

- The referendum in the Sylhet district led to its incorporation into East Bengal, and the referendum in the North-west Frontier Province (NWFP) decided to join Pakistan.

Evaluation of Mountbatten Plan

- While the partition seemed inevitable, Mountbatten’s plan was in favour of retaining maximum unity and keeping Pakistan as small as possible. This was evident when Mountbatten supported the Congress’ position on Hyderabad.

- The date of transfer of power was advanced to get Congress to agree to the dominion status. In addition, the British could absolve themselves of the deteriorating communal situation.

- The speed at which the whole plan was executed (72 days) proved disastrous; it resulted in large-scale violence, particularly in Punjab, where there was a lack of transitional structures to tackle the complexities of the partition.

- The announcement of the Radcliffe Commission was delayed to 15 August to escape responsibility for the anarchic situation.

Indian Independence Act 1947

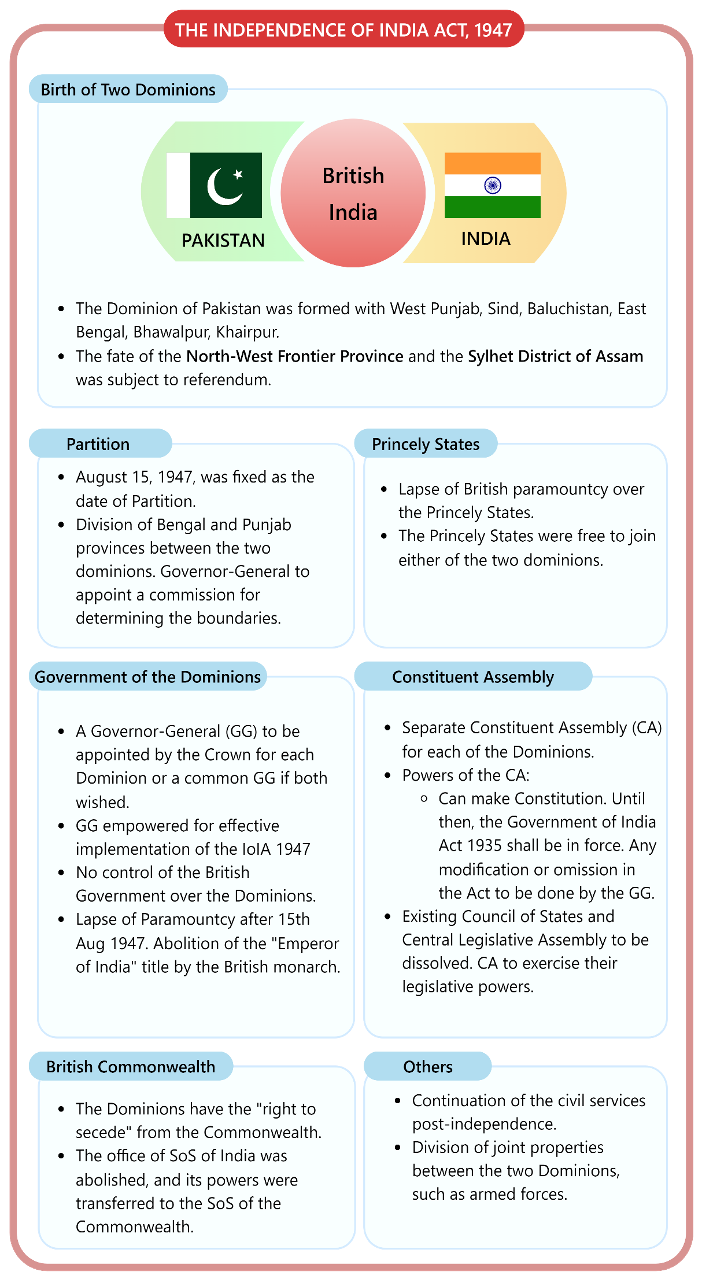

On 5 July 1947, the British Parliament passed the Indian Independence Act, incorporating the Mountbatten Plan. The act got royal assent on 18 June 1947. It came into effect on 15 August 1947. The main points of his announcements were:

- The British suzerainty over the Indian states would lapse with effect from 15 August 1947, and the states could either join India or Pakistan.

- The act provided for the partition of British India into two dominions, India and Pakistan, with effect from 15 August 1947.

- Each dominion was to have a Governor-general as the representative of the Crown.

- The Central Legislative Assembly, along with the Council of States, were to be dissolved, and the constituent assemblies of both dominions were to also act as legislative assemblies of that dominion.

- Until the new constitutions were adopted, the governments of the two dominions were carried on in accordance with the Government of India Act of 1935.

Acceptance of Partition by the Congress

- Due to the long-term failure to engage the Muslims in the national movement, Congress was merely accepting the inevitable. It failed to integrate Muslims into the nation.

- It was the ultimate outcome of step-by-step concessions and legitimacy provided to the League’s cause of separatism.

- The obstructionist approach of the Muslim League in the interim government and large-scale violence convinced the Congress leaders that there was no alternative to partition.

- The helpless Congress leaders within the interim government thought that an immediate transfer of power would at least enable them to exercise power to check the widespread riots.

- As a concession to the Congress for agreeing to the Mountbatten plan, independence to the princely states was ruled out.

- There was also wishful thinking within the Congress that Hindus and Muslims would iron out their differences once the British left, and the partition would be reversed.

- Gandhi’s position:

- Gandhi accepted the partition because the people wanted it, and he had no choice.

- The main reason for Gandhi’s helplessness was the communalisation of the masses. He assessed that both Hindus and Muslims had moved far from non-violence.

- In his last-ditch attempt to prevent the partition, he even suggested prime ministership of United India to Jinnah; however, his offer was not endorsed by the Congress Working Committee.

- There was also an expectation that the partition could be revoked when the British left and passions from both sides subsided.

Integration of Princely states

- The rising national consciousness and increasing awareness about democracy, civil liberties and responsible governments in the rest of India were influencing the people of princely states.

- During 1946-47, there was a new upsurge in the people’s movement in the states demanding political rights and representation in the constituent assembly through elections.

- Nehru remarked that independent India would not accept the divine rights of the King. He presided over the meetings of the All-India States People’s Conference (AISPC) In 1945 and 1947, where he remarked that states would be treated as enemy states if they refused to join the constituent assembly.

- Vallabhbhai Patel held the states department and used the diplomacy of Saam, Daam, Danda, and Bheda (advice, offer, coercion & blackmail) to incorporate the states into the Indian union.

- By the end of 15 August 1947, all princely states (more than 550) except Hyderabad, J&K and Junagarh had signed the instrument of accession with the Indian state acknowledging the federal authority over defence, communication and external affairs.

- The next phase of political integration involved more complications like the merger of smaller states, internal constitutional changes, etc., which we will discuss in “Post-independence India”.

![Home Rule Movement (1916-1918): India'S Fight For Self-Governance [Upsc Notes] | Updated March 13, 2026 Home Rule Movement (1916-1918): India’S Fight For Self-Governance [Upsc Notes]](https://99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/home-rule-featured-66698a5b2a805-768x500.webp)