Directive Principles of the State Policy (DPSPs)

Directive Principles of the State Policy (DPSP)

Part IV (Articles 36 to 51) of the Constitution constitutes the Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSPs). The Constitution added these principles to bring about social and economic justice to the people. These directive principles embody the principles of a welfare state.

These directives are addressed to the state and do not grant enforceable rights to the citizens; however, as Article 37 states, these directive principles are fundamental to the governance of the country and the state is expected to apply these principles in making laws.

In Granville Austin’s views, Directive Principles of State Policy have been helpful in achieving the constitutional objectives of social, economic and political justice for all.

Genesis of the Directive Principles of the State Policy

- The provisions mentioned in these principles were influenced by the nationalistic and socialistic ideals prevalent in India since the 1920s.

- The Karachi resolution of 1931 mentions several socio-economic principles that later became part of the Constitution, such as the abolition of child labour, free primary education, and protection of agricultural and industrial labour. The resolution also had Gandhian influence as it mentions the prohibition of intoxicating drinks and drugs.

- The Sapru Committee of 1945 recommended the separation of rights into two parts – justiciable and non-justiciable. The Fundamental Rights in our Constitution are Justiciable, whereas DPSPs are non-justiciable.

- The Directive Principles also have similarities with the “instrument of Instruction” enumerated in the Government of India Act 1935.

- The provisions of the Directive Principles of the State Policy were borrowed from the Irish Constitution.

Features and Utility of the Directive Principles

- Non-enforceable but fundamental to the governance: The provisions contained in this part are non-enforceable; however, the principles formulated are fundamental in the governance of the nation. The Constitution directs the state to apply these principles while making laws.

- Lay down the foundation for the welfare state: They seek to establish socio-economic democracy in the country. These principles constitute a comprehensive social and economic programme essential for establishing a welfare state.

- Plays a Role in determining the constitutional validity of a law: Even though these principles are not justiciable, they help the judiciary in examining the constitutional validity of a law. Courts may consider provisions in a law ‘reasonable’ in the context of Articles 14 and 19 if they are meant to implement directive principles.

- Provides continuity and stability: It provides continuity and stability in the domestic and international sphere despite the change of party in power. They also serve as a common manifesto across the political parties.

- Supplements Fundamental Rights: It supplements fundamental rights by making provisions for economic rights (though not enforceable).

- Checks Executive: It enables the opposition parties to pressurise the executive for the implementation of these directive principles.

- It amplifies the values present in the preamble.

Difference between Fundamental Rights and Directive principles:

Fundamental Rights Vs Directive Principles |

|

|

These are negative rights, which means they restrict the state’s authority to encroach upon these rights. |

These can be considered positive rights since they provide, not deny. |

|

These are justiciable rights, which means a person can go to court for enforcement of these rights. |

These are non-justiciable rights but act as guiding lights for the governance of the state. |

|

Usually, they do not need separate legislation for their enforcement. |

They can come into effect only when legally implemented. |

|

These rights are more concerned with the establishment of political democracy. |

Directive principles seek to address socio-economic issues. |

|

Fundamental rights focus on individual rights. |

Directive Principles focus on the welfare of the entire community. |

Reasons behind making the Directive Principles non-justiciable

On the recommendation of BN Rau, constitutional advisor to the constituent assembly, rights were divided into two categories: Justiciable and non-justiciable. The reasons behind this approach towards rights were:

- Financial Reason: The British had left a financially resource-scarce country that did not have sufficient resources to implement these rights.

- Social reason: The vast diversity, backwardness, and regional disparities would come in the way of its implementation.

- Administrative reason: The country was already dealing with the horrors of the partition and innumerable fault lines within the country, so it made sense to implement these rights on a piecemeal basis.

Classification of the Directive Principles

Based on the nature and scope, the Directive Principles can be classified into:

- Socio-Economic Principles;

- Gandhian Principles;

- Policies and Principles related to International Peace and Security.

The Socio-Economic Principles: |

| The state shall endeavour to achieve the Social and Economic welfare of the people by:

1. Article 38: Minimising the inequalities in income and endeavour to eliminate inequalities in status, facilities and opportunities, not only amongst individuals but also amongst groups of people residing in different areas or engaged in different vocations. 2. Article 39 a) Providing adequate means of livelihood for both men and women. b) Reorganising the economic system in a way to avoid the concentration of wealth in a few hands. c) Securing equal pay for equal work for both men and women. d) Securing suitable employment and healthy working conditions for men, women and children. e) Guarding children against exploitation and moral degradation. 3. Article 39 A: To make arrangements for the disbursement of free legal justice through suitable legislation. 4. Article 41: Making effective provisions for securing the right to work, education and public assistance in case of unemployment, old age, sickness and disablement. 5. Article 42: Making provisions for securing just and humane work conditions and maternity relief. 6. Article 43: Securing for all the workers’ reasonable leisure and cultural opportunities. 7. Article 43A: Taking steps to secure the participation of workers in the management of undertakings, etc. 8. Article 45: Providing early childhood care and education to all children until the age of 6 years. [Note: providing education between the ages of 6 and 14 is now a fundamental right under Article 21A.] 9. Article 46: Promoting education and economic interests of working sections, especially the SCs and STs. 10.Article 47: Efforts to raise the standard of living and public health. |

The Gandhian Principles: |

|

A few principles enshrined in the DPSPs are based on the ideals advocated by Gandhiji. These Principles are as follows: – 1. Article 40: To organise village Panchayats. 2. Article 43: To promote cottage industries in rural areas. 3. Article 47: To prohibit intoxicating drinks and drugs that are injurious to health. 4. Article 48: To preserve and improve the breeds of the cattle and prohibit the slaughter of cows, calves and other milch and drought animals. |

DPSPs Relating to International Peace and Security: |

Article 51: India shall endeavour to: –

|

Miscellaneous: |

The Directive Principles in this category call upon the state:

|

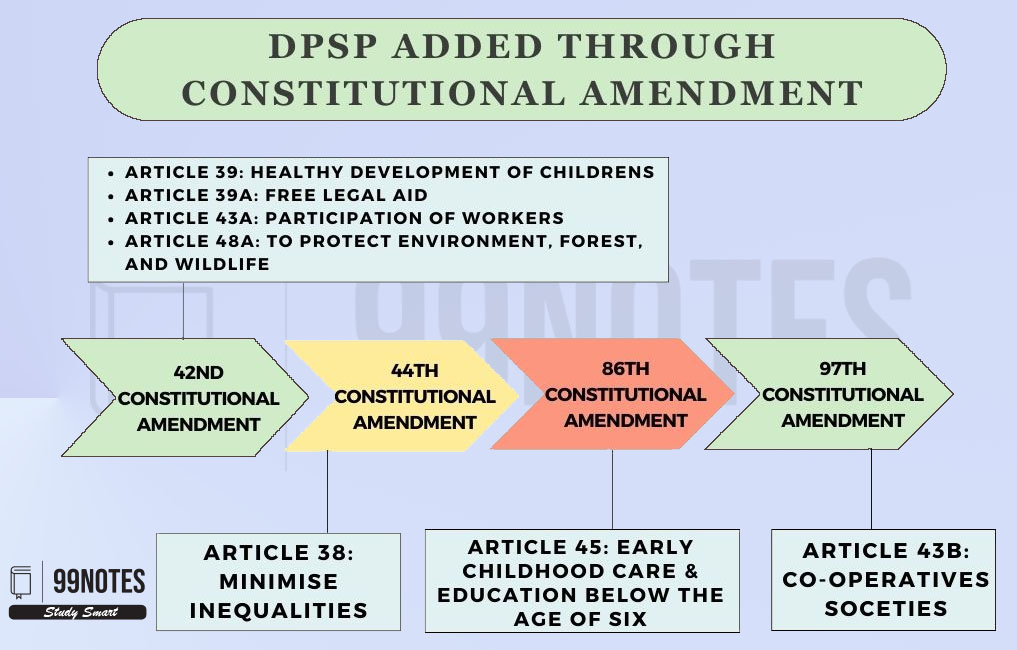

Amendments in the Directive Principles of State Policy

Several new clauses were added to the Directive principles to further the cause of social welfare.

- The 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act, 1976 added four new subjects in the Directive Principles that required the state to:

-

- Article 39: Provide opportunities for the development of children in a healthy manner.

- Article 39A: to promote justice on the basis of equal opportunity and to provide free legal aid to the poor.

- Article 43A: to secure the participation of workers in the management of industries.

- Article 48A: to protect the environment, forest and wildlife.

- The 44th Constitutional Amendment Act 1978 added Article 38, which required the state to minimise inequalities in income, status, facilities and opportunities.

- The 86TH Constitutional Amendment Act 2002 changed the content of Article 45; it required the state to provide early childhood care and education for all children until they complete the age of 6. The original directive principle was made into a fundamental right under Article 21A, which guarantees free and compulsory education to children aged six to fourteen.

- The 97th Constitutional Amendment Act 2011 inserted Article 43 B, which required the state to promote voluntary formation, autonomous operation, democratic control and professional management of co-operative societies.

The Conflict between Directive Principles and Fundamental Rights

Both the fundamental rights and directive principles share the same goal, which is the protection of rights and social welfare. Constitutional expert Granville Austin called both of them the “conscience of the constitution”.

However, the justiciability and enforceability of the fundamental rights (which gives it a superior status) and the moral obligation of the state to implement directive principles led to conflict between the two of them.

- State of Madras vs. Champakam Dorairajan Case, 1951: In this case, the Supreme Court declared the directive principles as subsidiary to the fundamental rights and hence, in any conflict, the fundamental rights would prevail.

- However, it also declared that the fundamental rights could be amended; hence, several amendments were made, including the First Constitutional Amendment Act (1951), to implement some of the directive principles.

- The Kerala Education Bill Case, 1958: In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that though the directive principles cannot override the fundamental rights, they should not be ignored while determining the ambit and constitutionality of the fundamental rights, and the principle of harmonious construction should be adopted.

- Golaknath Case, 1967: In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that Parliament cannot take away any fundamental Right. It means fundamental rights could not be amended to implement the directive principles.

- In response, the Parliament enacted the 24th and 25th Constitutional Amendment Act The 24th Amendment Act made a provision that the Parliament has the power to amend or repeal any fundamental right.

- The 25th Amendment Act inserted Article 31C, which made a provision that laws meant to implement the directive principle in Article 39 (b) and (c) cannot be declared void on the grounds of violation of fundamental rights protected under Article 14, 19 and 31 (now repealed).

- In the Kesavanand Bharti Case, 1973, the Supreme Court upheld the above provision. It also maintained that both the fundamental rights and DPSPs are supplementary and complementary to each other.

- 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act: This amendment extended the scope of Article 31C by including any of the directive principles and not merely given in Article 39 (b) and (c).

- Minerva Mills Case (1980): The Supreme Court, in this case, declared that the addition mentioned above in Article 31C was unconstitutional. It means the directive principles were once again declared subordinate to the fundamental rights.

- Articles 14 and 19 are subordinate to the directive principles mentioned in Articles 39 (b) and (c).

- In this case, the Supreme Court also mentioned that the “Indian Constitution is founded on the bedrock of the balance between the fundamental rights and DPSPs. The harmony between them is the basic structure of the constitution”.

- Current position: The present status of the relation between the fundamental rights and DPSPs is that the Parliament has the authority to amend the fundamental rights to implement the directive principles as long as the amendments do not affect the basic structure of the Constitution.

Implementation of the Directive Principles of State Policy

The directives principles have served as a guiding principle in the preparations of various policies, legislations and schemes. Some of them are mentioned below:

- Planning Commission: The erstwhile Planning Commission aimed to bring social and economic justice through its five-year plans. The NITI Ayog, which replaced the planning commission, aims to achieve the same, though with a different approach that involves medium and long-term planning.

- Land Reforms: Most of the states undertook Land reforms to restructure the agrarian system; it involved:

- Zamindari abolition

- Tenancy reforms

- Ceilings on land holding

- Co-operative farming

- Schemes/Laws for Unprivileged Sections: Subsequent governments have taken several initiatives to help the unprivileged sections and protect their interests:

- Providing free legal aid to the poor (Legal Service Authorities Act, 1987)

- Ensuring minimum wage to workers (The Minimum Wages Act, 1948)

- Protecting contract workers (Contract Labour Regulation and Abolition Act, 1970)

- Abolition of bonded labour (The Bonded Labour System Abolition Act, 1976)

- Resolution of industrial disputes (Industrial Disputes Act, 1947)

- Abolition of Child labour (Banned in 2006)

- Women Empowerment: The Maternity Benefit Act of 1961 and the Equal Remuneration Act of 1976 were passed to protect the interests of women.

- Wildlife and Environment Protection: The Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 and the Forest Conservation Act of 1980 were passed to protect wildlife and forests. Similarly, The Water Act and Air Act were passed for the protection and improvement of the environment.

- Promotion of Cottage Industry: The government established the Khadi and Village Industrial Board, Handicraft Board, Silk Board, etc., to promote the cottage industry.

- Protection of Ancient and Historical Monuments Act: The government enacted laws for the protection of ancient and historical monuments, archaeological sites and remains, and other places of national importance.

- Interests of SC and ST Class: The government has made provisions for the reservation of seats in Loksabha, state assemblies and reservation of seats in public employment and academic institutions. Similarly, The Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1976 and Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 were passed to protect their interests.

- Institution of Panchayati Raj: The 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act established a 3-tier Panchayati Raj system.

- Prohibition of Slaughter of Cows: Many states have enacted laws to ban the slaughter of cows and calves.

- Affordable Healthcare and Education: Free and compulsory education for children, early childhood care programmes, and affordable healthcare (NRHM, Ayushmaan Bharat) were instituted to raise the living standards of the people.

- International Peace: India has been following a non-alignment foreign policy and supports multilateral institutions like the United Nations to promote international peace and security.

Limitations of the Directive Principles

- Not Legally Bound: The government is not legally bound to implement them, despite it being part of the Constitution. Its non-justiciability may make the state vulnerable to the pressure exerted by politically and economically influential groups.

- The non-justiciability of the principles made the members of the constituent assembly describe them as “pious wishes” (KT Shah), “a veritable dustbin of sentiments” (T.T. Krishnamachari).

- No Consistent Philosophy: The directive principles have been criticised by Sir Ivor Jennings for not having a consistent philosophy; similar criticisms come from other scholars as well. These principles are also criticised for being illogically arranged. For example, Several vital issues have been mixed with relatively less important ones.

- Causes of Conflict between Institutions: As we have already discussed, the implementation of these principles has led to conflict between the executive and judiciary. K Santhanam, a member of the constituent assembly, asserted that these directives could lead to conflict between Centre and state, Prime Minister and President, Chief Minister and governor on the issue of its enforcement.

- Outdated Political Economy: Critics like Ivor Jennings argue that these directive principles are inspired by Fabian Socialism (Democratic Socialism), which was relevant in 19th century England. They express scepticism about whether these principles will be suitable in a non-socialist, 21st-century India.

Despite these limitations, these directives cannot be ignored, as they act just like a polestar, guiding the country in its goal to achieve social and economic justice for its people.

These aspirations mirror public opinion and reflect the ideals and values enshrined in the preamble of the Constitution, which no government can afford to ignore.

Conclusion

The Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSP) serve as a guiding framework aimed at establishing a welfare state in India. Despite being non-justiciable, they hold significant importance in the governance of the country, urging the state to apply these principles in law-making. They reflect the aspirations for social, economic, and political justice, emphasizing the Constitution’s commitment to creating an equitable society. The DPSPs embody the ideals and values that support the country’s progress towards achieving comprehensive welfare for all its citizens.

![Fundamental Rights Of Indian Constitution: Article12-35 [Indian Polity Notes For Upsc Exams] | Updated February 24, 2026 Fundamental Rights Of Indian Constitution: Article12-35 [Indian Polity Notes For Upsc Exams]](https://99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/fundamental-rights-banner-99notes-651fdb2e2cee1.webp)