The Doctrine of Basic Structure

“Without the basic structure, we end up with a constitution without constitutionalism”.

-Upendra Buxi

How comprehensively can Parliament amend the Constitution? Can it change the very nature of the Constitution? Can it rewrite the whole Constitution?

These were the questions that our Supreme Court, the final interpreter of the Constitution, faced in the 1960s and 70s when, in just 10 years, more than 20 amendments were made. Some of which challenged the very basis of the Fundamental Rights.

Thus, the Supreme Court came up with the doctrine of Basic Structure. It is a Judicial innovation based on the idea that a change in the Constitution does not involve its destruction. There is an underlying basic structure that the Parliament cannot change. Only a constituent Assembly has the power to rewrite the Constitution.

The doctrine of basic structure continues to evolve with the judicial pronouncement of the Supreme Court. Its essence lies in those features, which, if amended, would change the very identity of the Constitution itself, ceasing its current existence.

The doctrine of basic structure was given in the Kesavanand Bharti Case, where the Supreme Court held that “every provision of the Constitution can be amended provided in the result the basic foundation and structure of the Constitution remain the same.”

- Regarding the amending power under Article 368, The Supreme Court in Kesavanand Bharti’s Judgement held that “one cannot legally use the Constitution to destroy itself”.

- This is inspired by the doctrine of basic structure in the German Constitution, which is based on the principle that democracy is not just a form of government but rather a philosophy of life that appreciates dignity and inalienable individual rights. These basic rights cannot be affected in any circumstances.

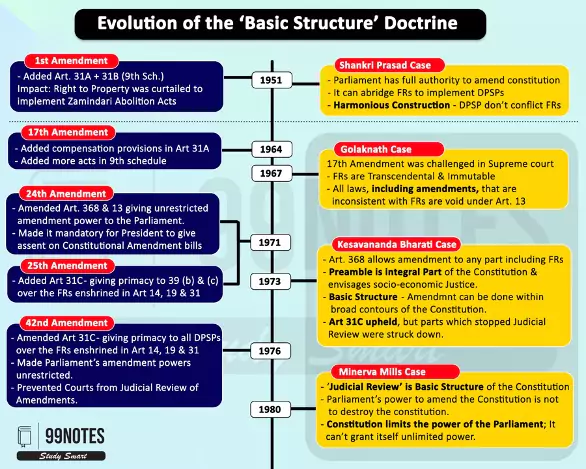

The emergence of the doctrine of Basic structure

The Parliament’s authority to amend the Constitution, especially the fundamental rights, became a subject of contestation as early as 1951. The Congress Party’s electoral promise of implementing the socialistic principles (abolition of inequality) in the Directive Principles came into conflict with the Right to Property.

Shankari Prasad Case (1951)

- This case came up with the First Amendment Act (1951), which added a 9th schedule to exclude such laws that restricted the Right to Property and was challenged in the Court.

- The government was trying to abolish the Zamindari by placing Land Ceiling Acts and Tenure Abolition Acts. It inserted Article 31A and the 9th Schedule in the Constitution, which was now outside the purview of Judicial review. Any state law which acted against the Zamindari system was added to the 9th schedule.

- The property owners (Zamindars) argued that this Amendment violates Article 13, which protects the fundamental rights of the citizens.

Article 13 |

| “Laws” inconsistent with or in derogation of the fundamental rights shall be void.

The term “law” includes any Ordinance, order, bye-law, rule, regulation, notification, custom or usage having in the territory of India the force of law; |

- In this case, the Supreme Court held that the word ‘law’ in Article 13 does not include a Constitutional Amendment Act. This means the Constitution can take away any fundamental right, and it will not be void under Article 13.

- Harmonious Construction: The Court found that the fundamental rights and the DPSPs are not conflicting ideals but are two sides of the same coin, and it would be beneficial if they worked together. Thus, fundamental rights can be amended to bring them into conformity with the DPSPs.

- Conclusion: The Parliament was fully competent to make any amendment to the Constitution. The authority of the Parliament under Article 368 also includes the authority to amend fundamental rights.

However, until 1967, it was observed that whenever the judiciary gave unfavourable Judgement, the government would bring amendments to overrule it. In 1964, the government brought the 17th Amendment to amend Article 31A and the 9th Schedule. It added 44 acts in the 9th Schedule in one go.

Golak Nath Case (1967)

- In the Golaknath case, the 17th Amendment was challenged, and the Supreme Court reversed its earlier decision. It equated the constituent power and legislative powers of the Parliament.

- Since a constitutional amendment is a legislative process, the term ‘Law’ also includes constitutional amendments. Thus, even constitutional amendments cannot be inconsistent with the Fundamental Rights.

- Therefore, it ruled that a Constitutional Amendment Act would also be void if it violates fundamental rights.

- Conclusion: The Fundamental Rights were given a ‘transcendental and immutable’ position; hence, they cannot be taken away.

24th and 25th Constitutional Amendment Act (1971)

After the Golaknath judgement, several policies of the Indira Gandhi government, like the abolition of privy purses to the erstwhile princes and the nationalisation of banks, were struck down by the Supreme Court.

The Parliament and Supreme Court were once again at loggerheads over the relation between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles as well as Parliamentary supremacy vis-a-vis the Court’s authority to interpret and uphold the Constitution.

The 24th Constitutional Amendment Act was brought to overrule the Golaknath judgement. The Act amended Article 13 and Article 368. The Provisions added were:

- It stated that the Parliament could abridge any of the fundamental rights under Article 368.

- Such a Constitutional Amendment Act would not be considered as ‘law’ in the context of Article 13.

- It also made it binding on the president to give assent to the Constitutional Amendment Act.

The government brought the 25th Amendment Act, which inserted Article 31C, giving primacy to Directive Principles mentioned in Article 39 (b) and (c) over fundamental rights contained in Articles 14, 19 and 31.

- It meant that when the government aimed to implement welfare provisions of the Constitution, the fundamental Right to Property could be violated, and this could not be challenged on the ground of equality before the law in the Court.

Conclusion: The 24th Amendment Act, which gave unrestricted power to the Parliament to amend the Constitution, and the 25th Amendment Act enabled the government to give primacy to the welfare provisions of DPSP over the Fundamental rights of equality, freedom and Property.

Article 39 (b) and (c) |

| 39. The State shall direct its policy towards securing—

(b) that the ownership and control of the material resources are so distributed as best to subserve the common good; (c) that the operation of the economic system does not result in the concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment; |

Article 31C (as introduced in 1971)Saving of laws giving effect to certain DPSPs |

Notwithstanding anything contained in Article 13,

Note: This is a version of Article 31C, which the Supreme Court validated in the Kesavanad Bharti Case, which still stands. |

Kesavanand Bharti Case (1973)

These circumstances compelled the Supreme Court to come up with the doctrine of the Basic structure. It made the following judgements:

- Parliament can amend even Fundamental Rights:

- Article 368 does not make any exception for Fundamental rights, which could make it immutable, thus reversing its decision given in the Golaknath Case.

- Thus restoring the Parliament’s amending power.

- On Preamble:

- The Preamble is an integral part of the Constitution, which proclaims securing economic and social justice for its citizens before ensuring equality and liberty. Thus, it upheld the validity of the 24th Constitutional Amendment Act, which aims at securing socio-economic Justice for Indian citizens.

- But, the Amendment should be done in the broad contours of the Preamble, i.e. liberty and equality as secured by the Fundamental Rights can be abridged only to secure reasonable public interest.

- Basic structure Introduced:

- It stated that “every provision of the Constitution can be amended provided in the result the basic foundation and structure of the Constitution remains the same.”

- Thus, the constituent power of the Parliament under Article 368 does not empower it to change the ‘basic structure’ of the Constitution beyond the broad contours of the Preamble.

- Portions of Article 31C struck down: The provision that stopped it from being called into question by any court was struck down.

Conclusion: The Parliament has the power to amend all parts of the Constitution as long as they are in tune with the Basic structure of the Constitution.

42nd Constitutional Amendment Act (1976)

During an emergency, the government brought the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act to remove the limits posed by the Kesavanand Bharti judgement.

- It again amended Article 31C to place all Directive Principles over the fundamental rights protected under Articles 14 and 19. It again did away with any scope of judicial review in case of amendments to fundamental rights.

- This Constitutional Amendment Act amended Article 368 and declared that the constituent authority of the Parliament is unrestricted, and no amendments can be questioned on the grounds of violation of fundamental rights.

Minerva Mills Case (1980)

The 42nd Amendment was challenged by a sick industrial firm, Minerva Mills, that was nationalised by the government and challenged the fact that the Judicial review of this decision was not available. The Supreme Court gave the following Judgement:

- It invalidated the 42nd Amendment in Article 368, which took away the rights of the judiciary to review the amendments in the Constitution.

- It held that ‘judicial review’ is a basic feature of the Constitution. It means that the Court protected the doctrine of the basic structure by invoking the doctrine itself.

- In this Judgement, the Court stated, “The features or elements which constitute the basic structure or framework of the Constitution or which, if damaged or destroyed, would rob the Constitution of its identity so that it would cease to be the existing Constitution but would become a different Constitution”.

- SC unanimously ruled that the power of the Parliament of India to amend the Constitution is limited by the Constitution. Hence, the Parliament cannot exercise this limited power to grant itself unlimited power. The power of the Parliament to amend is not to destroy the Constitution.

Nani Palkhivala |

| Nani Palkhivala was the lead counsel in the famous Golaknath case, Kevananda Bharati Case and the Minerva Mills case, who helped the Supreme Court to shape the doctrine of Basic structure using the arguments to preserve the cardinal Principles of the Indian Constitution. |

Waman Rao case (1981)

In this case, the Supreme Court examined the validity of Articles 31A and 31B. The Court reiterated the Basic structure doctrine and also held that this doctrine would not be applied retrospectively and amendments made before 24th April 1973 (the day of Kesavanand judgement) would not be scrutinised on the basis of the basic structure doctrine.

Current Position of the Basic Structure

Current Position of the Basic Structure

- Parliament can amend any part of the Constitution under Article 368.

- However, there is a “basic structure” implicit in the Constitution that the Parliament cannot change.

- The Supreme Court is fully competent to review all Constitutional amendments to strike down if they violate this basic structure. Thus, the Supreme Court is the sole interpreter of the Basic structure.

- This doctrine cannot be applied retrospectively to the amendments made before 24th April 1973 (the day of Kesavanand judgement).

Constitutional Provisions that form the Basic Structure

The Supreme Court has not yet defined what constitutes the basic structure. The doctrine has evolved with various judgments of the Courts, which have been mentioned below:

- Kesavanand Bharti Judgement (1973)

This Judgement laid down the first list of features of the doctrine.

- Supremacy of the Constitution;

- Republican and Democratic forms of government;

- Parliamentary system;

- Separation of powers between the judiciary, the executive and the legislature;

- Federal character of the Constitution;

- Secular nature of the Constitution;

- Unity and Integrity of the nation;

- The dignity of the individual is secured by the various Fundamental Rights and the programme of action to establish a welfare state contained in the directive principles.

- Indira Gandhi Vs Rajnarain Case Judgement (1975)

In this case, the Court nullified clause 4 of Article 329A, which provided for special provisions for the election of the Prime minister and Speaker. The Court expanded the scope of the basic structure and identified four unamendable features of the Constitution.

-

- India is a sovereign democratic republic;

- Equality of status and opportunity shall be guaranteed to all its citizens;

- There shall be no official religion of the State, and everyone shall have the same Right to religious freedom, including the Right to freely practice, profess, and propagate one’s religion;

- The nation shall be governed by a government of laws, not of men (Rule of Law).

- The Court also noted that free and fair election is an essential tenet of democracy, which is a basic feature of the Constitution.

- Minerva Mills Case (1980): The Court identified ‘judicial review’ as the basic feature of the Constitution. Further:

-

- In L Chandra Kumar’s case (1997), the Court recognised that the power vested in the Supreme Court and High Courts under Articles 32 and 226 is the basic feature of the Constitution.

- In the IR Coelho case (2007), while examining the provisions protected under the 9th Schedule, the Court maintained that judicial review is the basic feature of the Constitution and the provisions added in the 9th Schedule after the Kesavanand Bharti judgement must pass the test of adherence to the fundamental principles stated in the Article 21, read with Article 14 and 19.

- Harmonious construction: It also held that harmony and balance between the fundamental rights and directive principles is a part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

Other Judgements:

- Delhi Judicial Service Association Case (1991): The Supreme Court observed that, Under the Constitutional arrangement, the Supreme Court has a distinct role in the administration of justice, and the authority conferred on it under Articles 32, 136, 141 and 142 is part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

- SR Bommai Case (1994): The Supreme Court explained the concept of basic structure while dealing with the issue of Article 356 (President Rule). The Court reiterated that secularism is the basic feature of the Constitution.

- M Nagraj case (2006): The Supreme Court observed that “axioms like secularism, democracy, reasonableness, social justice, etc. are overarching principles which provide a linking factor for principles of fundamental rights like Articles 14, 19 and 21. These principles are beyond the amending power of Parliament”.

- Kuldip Naiyar Case (2006): The Parliamentary democracy and the multi-party system are the inherent part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

- Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association Case (99th CAA) 2015: the supremacy of the Constitution, the federal character of distribution of powers, the Republic and democratic form of government, separation of powers between the Legislatures, Executive and the Judiciary, independence of the judiciary and secularism.

- K Puttaswamy Case (2017): The right to equality (Article 14) and the Right to life (Article 21) were identified as the basic features of the Constitution.

Critical Analysis of the Basic Structure Doctrine

- Establishes the Supremacy of the Constitution: By establishing the judicial review as the basic structure and limiting the power of Parliament in matters of Constitutional Amendment, the doctrine has restored the supremacy of the Constitution as envisaged by the Constitution makers.

- Balance between Judiciary and Legislature: Granville Austin argues that the doctrine has established a balance between the powers of the Parliament and the Supreme Court.

- Protects the Constitution: As per Upendra Baxi, “Without the basic structure, we end up with a constitution without constitutionalism”.

- Ambiguous: The doctrine has not been clearly defined by the judiciary. Its nature and extent of the basic features of the Constitution continue to evolve, which may result in judicial overreach.

- Judicial overreach: Raju Ramachandran, former solicitor General of India, criticises the doctrine on the basis that the unelected judges have assumed the political power not given to them by the Constitution.

![Fundamental Rights Of Indian Constitution: Article12-35 [Indian Polity Notes For Upsc Exams] | Updated February 17, 2026 Fundamental Rights Of Indian Constitution: Article12-35 [Indian Polity Notes For Upsc Exams]](https://99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/fundamental-rights-banner-99notes-651fdb2e2cee1.webp)

![Salient Features Of Indian Constitution [Upsc Notes] | Updated February 17, 2026 Salient Features Of Indian Constitution [Upsc Notes]](https://99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/salient-features-of-indian-constitution-banner-99notes-upsc-654cce9bf3d76.webp)

![Centre State Relations- Legislative, Administrative, And Financial [Upsc Notes] | Updated February 17, 2026 Centre State Relations- Legislative, Administrative, And Financial [Upsc Notes]](https://99notes.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/central-state-relation-featured-768x500.webp)