Union and its Territory UPSC

Considering the vast diversity of this subcontinent, the framers of the Indian constitution created a federal Union structurally based on the Government of India Act 1935. It was a highly centralised structure; however, regional political forces have always worked towards reducing the centre’s grip over the states.

Articles 1 to 4 of the Constitution addresses the Union and its territories. Presently, there exist 28 states and 8 union territories.

India – A Union of States

- Article 1 of the constitution describes India, that is, Bharat, as a Union of states.

- In the absence of unanimity in the constituent assembly regarding the name of the country, it was decided to adopt both the traditional name Bharat, as well as the Modern name India.

- Despite adopting a federal scheme in the constitution, the phrase ‘Union of India’ has been used instead of ‘federation of states’. Dr BR Ambedkar clarified this by giving reasons:

- Indian Federation is not the consequence of an agreement of states as in the case of the American Federation.

- The states have no right to secede from the federation. It’s a union because it is indestructible.

- Classification of territories: Article 1 classifies the territory of India into three categories:

-

-

- Territories of the states.

- Union territories.

- Territories that the Government of India may acquire at any time.

-

- The names of states and the Union territories and their territorial extent can be in the 1st schedule of the constitution.

- The ‘Territory of India’ and the ‘Union of States’: The ‘Territory of India’ is a wider expression than the ‘Union of India’ since the latter only includes the states while the former includes not only the states and the Union territories but also the territories which the Government of India may acquire at any given time.

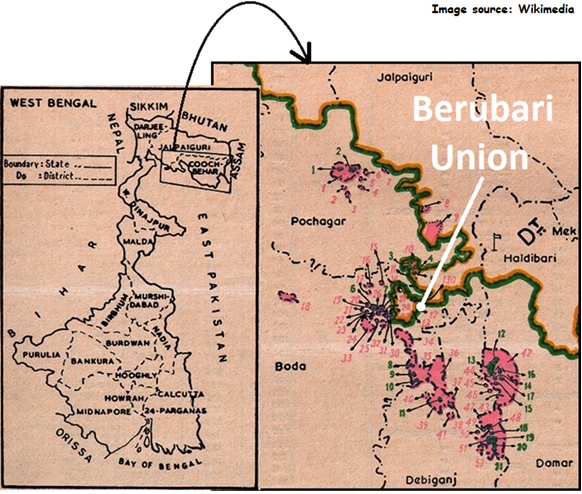

- Acquisition of Foreign territory: Foreign territories can be acquired through the means recognised by International laws, i.e. Cessation (following treaty, purchase, gift, lease or plebiscite), Occupation (territory unoccupied by a recognised ruler, conquest or subjugation). For example, the acquisition of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Goa, Daman and Diu and Sikkim by India).

- Article 2 empowers the Parliament to admit and establish new states into the Union of India. Establishing a new state refers to states which are not in existence before.

- Article 3 deals with internal adjustments of the states of the Union of India.

Parliament’s authority regarding the reorganisation of the states

The Parliament enjoys unrestricted powers in the matters of reorganisation of the states and the Union territories. It can change the political map of India at its will. It has been rightly described as an “indestructible union of destructible states”.

- Article 3 authorises the Parliament to:

-

- Create a new State by carving out territory from any State or by merging two or more States or parts of States or by merging any territory to a part of any State;

- Increase the area of any State;

- Diminish the area of any State;

- Alter the boundaries of any State;

- Alter the name of any state.

- However, the article provides for two conditions:

-

- The bill which proposes such changes can not be introduced in the Parliament except with the prior recommendation of the President.

- The bill has to be referred by the President to the concerned legislature of the state to express its view within the specified period. However, the President is not bound by the views expressed by the legislature. Furthermore, in the case of Union territory, no such reference is required to be made to the concerned legislature.

- Article 4 states that the laws made under Article 2 (admission and establishment of new states and Article 3 (formation of new states, alteration of boundaries, areas and names of states) are not considered constitutional amendments under Article 368. Thus it needs only a simple majority (like ordinary legislation) to enact the legislation.

Organisation of States Post-Independence India

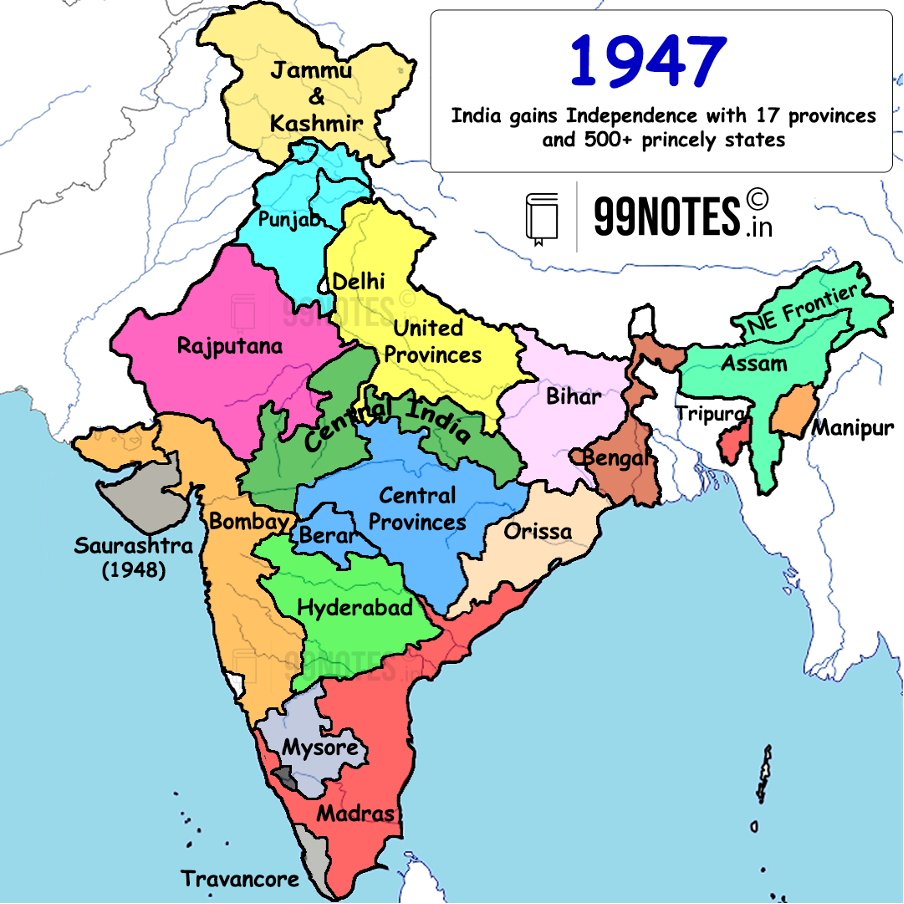

Independent India inherited a loose political-administrative structure from the British. The initial task of the Constituent Assembly and the interim government was to organise this structure with a rational framework. The foremost task was the integration of the princely states.

- At the time of independence, there were two kinds of political units; the British Provinces (directly administered by the British government) and the Princely states (ruled by Princes but under the paramountcy of the British crown).

- At the time of the independence, there were 550-odd princely states existed. In the Indian Independence Act (1947), these states were given the option of either joining the Dominion of India and Pakistan or remaining independent (However, as per the Mountbatten Plan, their independence was ruled out).

- All of the princely states situated within the geographical boundaries of India signed the instrument of accession and joined India, except for the princely states of Hyderabad, Junagarh and Jammu and Kashmir. Ultimately, these states were also integrated with India; Hyderabad through police action, Junagarh by means of a referendum, and Jammu and Kashmir signed the instrument of accession after facing invasion from Pakistani tribal militia.

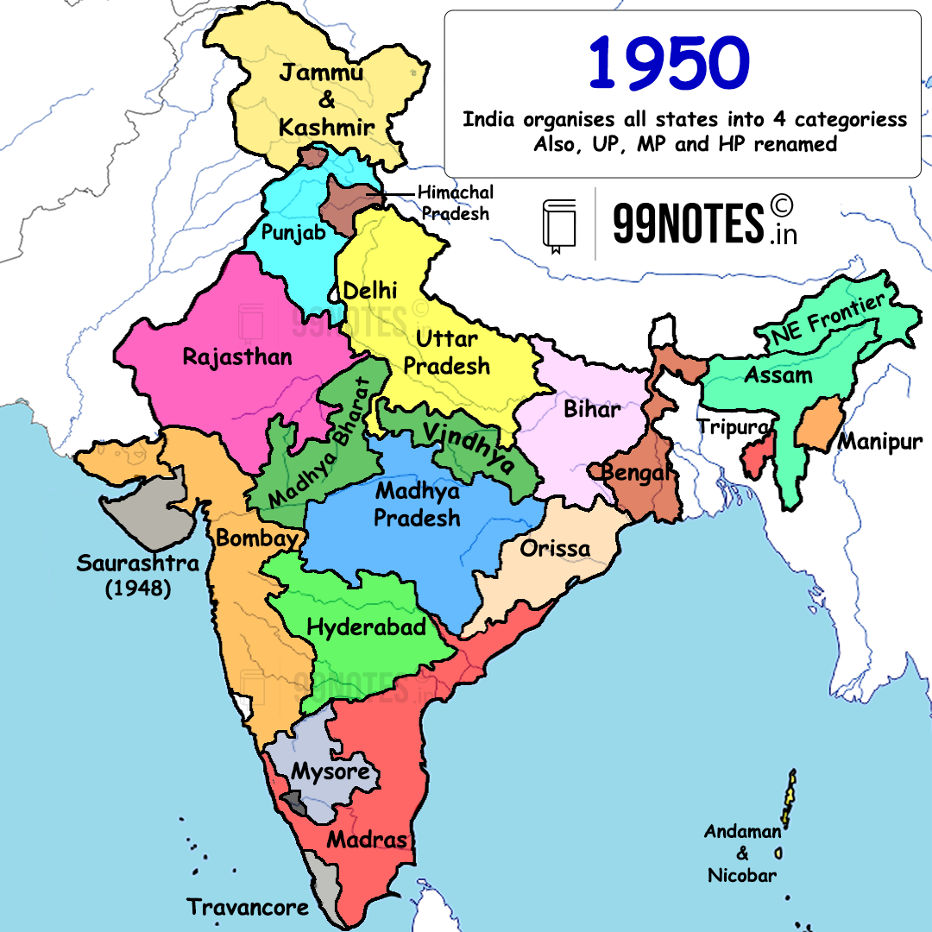

Grouping of states

- The major provinces of British India (Bihar, Bombay, the Central Provinces and Berar, Madras, Orissa and the United Provinces (renamed as Uttar Pradesh), Assam, East Punjab and West Bengal were grouped as Part A

- Major princely states that joined India formed Part B.

- Smaller princely states and some old chief commissioner’s provinces constituted Part C.

- The extremely backward Andaman and Nicobar Islands were constituted as a Part D

| Category | Description | Administrator | States |

| Part A states | Former British provinces | An elected governor and state legislature | 9 states: Assam, Bihar, Bombay, East Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Madras, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal |

| Part B states | Former princely states | Rajpramukh

(Former Princes) |

9 states: Hyderabad, Jammu and Kashmir, Mysore, Madhya Bharat, Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU), Rajasthan, Vindhya Pradesh, Travancore-Cochin, and Saurashtra |

| Part C | Former princely states and provinces | Chief Commissioner/

LG |

10 states: Ajmer, Coorg, Cooch-Behar, Bhopal, Bilaspur, Delhi, Himachal Pradesh, Kutch, Manipur, and Tripura |

| Part D | Union Territory | Chief Commissioner appointed by the President | Andaman and Nicobar Islands |

Linguistic Demands and State Boundaries

The demand for the reorganisation of states on a linguistic basis was not a phenomenon in Independent India only; it existed in British India as well.

- The anti-partition agitations in Bengal inspired linguistic aspirations in other parts of India, like the Andhra region of Madras province and Orissa.

- In 1920, the Congress organised its party units on the basis of language.

- In 1930, in the Madras session, the Congress adopted a resolution demanding provinces on a linguistic basis.

- In 1928, the All Party Conference acknowledged Sindhi as a distinct language and did not protest the formation of Sindh province.

- However, the traumatic experiences that emanated from the partition of India made the Constituent Assembly hesitant to grant linguistic states immediately.

Dhar Commission and JVP Committee

- Demands from different parts of the region, especially the southern states, to organise states on a linguistic basis led to the constitution of a commission under the chairmanship of SK Dhar in June 1948.

- The commission recommended administrative convenience as the basis of reorganisation and not language.

- The resentment caused by the report of the Dhar Commission led to the appointment of another committee by the Congress with members including Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel and Pattabhi Sitaramayya, hence the name JVP Committee.

- The committee submitted its report in April 1949 and rejected language as the basis of the reorganisation of states.

- In 1953, the Andhra agitation intensified after the fast death of a Gandhian leader, Potti Sriramalu. The government was compelled to form the state of Andhra Pradesh by separating the Telugu-speaking regions from the Madras state.

State Reorganisation Commission (Fazl Ali Commission)

- The formation of Andhra Pradesh escalated the demands from other regions.

- In 1953, the government appointed the state reorganisation commission under the chairmanship of Fazl Ali.

- The commission rejected the theory of ‘one language-one state’; however, it broadly accepted language as the basis of the reorganisation of states.

- It advocated that the unity of India should be the primary consideration in the reorganisation of the state.

- It recommended the conversion of the four different types of states into two categories; States and Union territories, and the merger of the former Part B state of Hyderabad with Andhra.

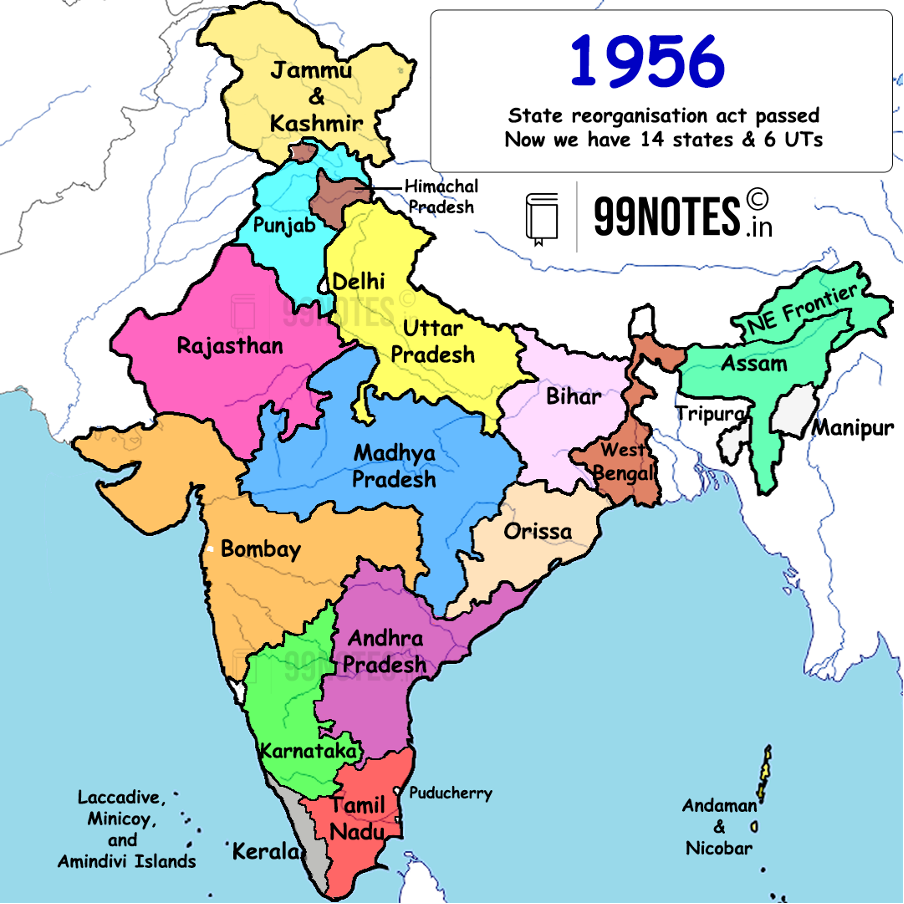

- On the basis of this report, the Parliament enacted the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, which did away with the fourfold classification, and states were divided into States and Union territories. It involved the merger of several smaller states into adjacent states.

- After this reorganisation, there existed 14 states and 6 Union territories.

Formation of States Post-1956 and Ethnic States

Even the large-scale reorganisation could not satisfy the demands for the formation of linguistic states. The further demands for the reorganisation of states on the basis of language, cultural homogeneity and ethnicity led to the bifurcation of existing states.

Gujarat and Maharashtra

- Language-based agitations led to the formation of Gujarati speaking state of Gujarat and Marathi speaking state of Maharashtra by dividing the Bombay state.

Dadra and Nagar Haveli

- The Portuguese-ruled state was liberated in 1954 and was administered by a local body till 1961, when it was constituted as a union territory by the 10th constitutional amendment act.

Goa, Daman and Diu

- These territories were also acquired from Portugal through police action in 1961.

- It was made a union territory in 1962 through the 12th constitutional amendment act.

- In 1987, Goa acquired statehood, and Daman and Diu were made into a separate Union territory.

- In 2019, the union territories of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu were merged to create a new union territory, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu.

Puducherry

- In 1954, the French handed over their establishments, namely, Puducherry, Yanam, Karaikal and Mahe, to India.

- These territories were administered as an acquired territory till 1962, when they were constituted into a union territory through the 14th Constitutional Amendment Act.

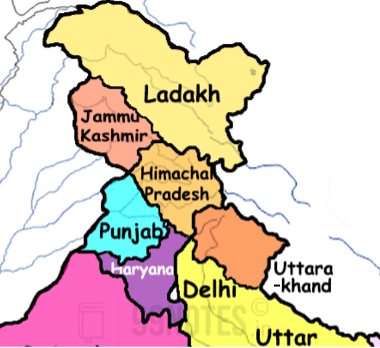

Haryana, Chandigarh and Himachal Pradesh

- Following the demand for a separate Sikh territory (Punjabi Suba) by Akali Dal under Master Tara Singh, the Shah Commission in 1966 recommended the bifurcation of Punjab and the formation of Punjab from Punjabi-speaking areas, formation of Haryana from Hindi-speaking areas and hilly areas merged with adjoining territory of the union territory of Himachal Pradesh.

- In 1971, Himachal Pradesh was conferred with the status of a state.

Sikkim

- Sikkim was a princely state in British India, ruled by Chogyal. Prior to its integration with the Indian Union, Sikkim existed as a ‘Protectorate’ of India as per the Indo-Sikkim treaty, whereby the government of India was responsible for defence, external affairs and communication.

- In 1974, the 35th Constitutional Amendment Act gave it the status of ‘associate state’, for these provisions were made under Article 2A and the 10th Schedule.

- Agitation for political reforms and abdication of the monarchy led to a referendum in which 97 per cent of the population favoured the abolition of the monarchy.

- Consequently, the 36th Constitutional Amendment Act was passed to make Sikkim a full-fledged state. This Act also added Article 371F to make special provisions regarding the administration of the state.

Telangana

- The state of Telangana was carved out of the state of Andhra Pradesh in 2014.

- During the regime of Nizam of Hyderabad, Telangana was part of Hyderabad State, while regions of current Andhra Pradesh were part of Madras State.

- Despite the common language, the people of Telangana were apprehensive after the merger with Andhra Pradesh due to the latter’s superior economic position.

- The longstanding demand was finally met with the division of Andhra Pradesh in 2014.

Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation |

|---|

|

Ethnic States

The emergence of ethnic states started in 1963 with the formation of Nagaland.

Nagaland

- The state of Nagaland was constituted by carving out the regions of Naga Hills and Tuensang areas out of Assam.

Manipur, Tripura and Meghalaya

- In 1970, the autonomous state of Meghalaya was created from the autonomous districts of Garo, Khasi and Jaintiya hills. In 1972, through the North Eastern Areas Reorganisation Act 1971, Meghalaya was promoted to the status of a full state with the merger of some non-tribal areas.

- The former Union territories of Manipur and Tripura were promoted to the status of full states, too, while two Union territories were carved out of Assam to form new Union territories:

- Arunachal Pradesh, formerly North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA)

- The Mizo Hills District with the name of Mizoram.

- In 1986 Mizoram and Arunachal Pradesh became full-fledged states.

Chhattisgarh, Uttarakhand and Jharkhand

- In 2000, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand were carved out from the tribal areas of Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, respectively, where the majority of the population was non-tribal.

- Same year Uttarakhand was created as a hill state by bifurcating the state of Uttar Pradesh.

What could be the reasons behind statehood demands?

Demands for statehood based on region, language, ethnicity and backwardness still persist in different parts of India. There can be several plausible explanations:

- The colonial period’s territorial arrangements were purely based on administrative grounds, overlooking linguistic, regional and ethnic diversity.

- India never had a centralised political structure of the kind the British created before; the boundaries in the pre-British period were based on ethno-cultural grounds, so when the British left, these old ethno-cultural linkages started asserting themselves as nationalities.

- The introduction of democracy and the grant of a universal adult franchise provided the aspiration for self-government.

- The weakening of the authority of big landlords after land reforms and prosperity ensued from the green revolution created a new class with aspiration for autonomy (Example- demand of Harit Pradesh in UP).

- With the spread of democratic consciousness and education, people became aware of regional disparities due to historical and geographical regions (Example- demand of Bundelkhand in UP).