Peasant Movements in India- Complete Notes for UPSC

Peasant Movements in India

Peasant movements in India have been pivotal in shaping the socio-political landscape, emerging as responses to oppressive feudal practices, high taxes, and exploitative colonial policies. Spanning from the 18th century to post-independence India, these movements varied in scope and impact, rallying for rights, fair land distribution, and against unjust economic burdens. They not only highlighted the grievances of the rural poor but also played a significant role in India’s broader struggle for social justice and independence.

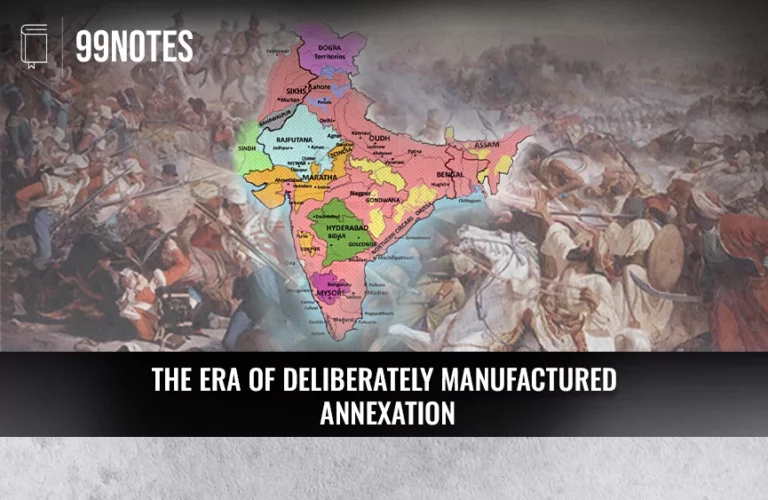

During the British rule in the 18th and 19th centuries, there were many uprisings against the ruling class. These uprisings resulted from the British’s economic policies, corrupt officials, unjust administration, oppression of zamindars and tax collecting officials, and interference of the British in tribal culture and their land.

In this chapter, we shall study the uprisings before revolt of 1857.

Peasant Movements in India:

Causes of Peasants’ Resistance Against the British

Peasants’ resentments against the British were due to the following reasons –

- The impoverishment of the Indian peasantry: During British rule, the Indian peasantry was affected severely due to the complete disruption of the old agrarian order of the tribal communities.

- Ruin of the traditional handicrafts: Due to the coercion of selling goods at low prices to the British, the conventional handicrafts reached their Nadir.

- Shifting of the vast labour force: Due to the destruction of the local industry, many workers moved from industry to agriculture. The demand for land increased, but the government’s land revenue and agricultural policy provided little room for developing Indian agriculture.

- The exploitative land revenue systems:

- This led to high rents, illegal levies, arbitrary evictions, and unpaid labour in the Zamindari areas.

- In Ryotwari areas, the government itself levied heavy land revenue.

- It distorted the traditional rural structure with the commercialisation of agriculture and the introduction of the market economy.

- Diluted conventional rights such as forest and pasture rights.

- This resulted in peasantisation, e., the conversion of tribals into peasants.

- Increased the caste and wealth divide.

- Converted the many land-owning peasants to mere tenants or landless labourers as they fell prey to the moneylenders to repay the tax.

- Ineffective judiciary system: Colonial administrative and judicial systems biased toward the white population were of little help to the peasants.

- The emergence of harsh famines: The periodic recurrence of famines worsened the rural communities.

Movement of Ryots/Peasants with the help of Zamindars

Royts were affected by the British policies, and they were instigated by the Zamindar to rise against the Britishers.

| Revolt | Characteristics of the revolt |

Revolt in Midnapore and Dhalbhum (1766–74) |

|

| Uprisings in Gorakhpur, Basti, and Bahraich (1781) |

|

Civil Resistance:

Causes of Civil Resistance against the British

Civilians’ (rulers, zamindars, chiefs, general people) resentments against the British were due to the following reasons –

- Changes in several existing systems: The rapid changes made by British rule in the administration, economy, and land revenue system were against the people.

- The British administration’s harsh and unjust treatment of people created resentment against it.

- Loss of territorial control of the zamindar class: Due to British rule, several zamindars and poligars misplacedcontrol over their land and its Moreover, they were sidelined in society due to a new class comprising merchants and moneylenders.

- Ruin of local handicraft industry: Handicraft was ruined by British policies, which made the artisans poor.

- Loss of Aristocats’ support: Priests and artisans had also lost their traditional patrons or buyers – princes, chieftains, and zamindars.

- Regional issues: Some uprisings were aimed at local causes and grievances against the ruling kingdoms.

| Revolt | Characteristics of the revolt |

| Surat Agitations (1844 and 1848) | · The Salt Agitation –

|

Politico-Religious Uprisings

In these uprisings, religion provided the basis for understanding the exploitative colonial rule and articulating the resistance. Some of these are –

1. Sanyasi/Fakir Revolt (1763–1800)

- Background –

- The East India Company’s officialcorrespondence in the second half of the 18th CE referred typically to the incursion of the nomadic Sanyasis and Fakirs, particularly in northern Bengal.

- Beforethe great famine of Bengal (1770), groups of Hindu and Muslim holy men (Sanyasi and Fakirs) travelled from place to place. They made surprise attacks on the granaries and property of the neighbourhood’s rich men and authority officers. They looted local government treasuries.

- They exact a religious tax from the local zamindars and headmen en route to the pilgrimage.

- However, due to the harsh revenue policy and famine, the zamindars could not give the tax to them.

- The famine brought many dispossessed Zamindars, disbanded soldiers and rural poor and peasants into the bands of Sanyasis.

- The revolt –

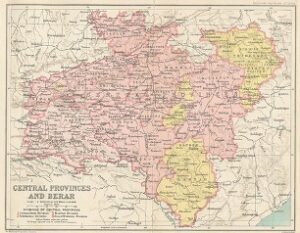

- They moved from place to place in Bengal and Bihar.

- They adopted the guerrilla technique to attack the local government’s treasuries and grain stocks.

- They distributed the wealth among the poor.

- The Sanyasi rebellionspiked in Bengal, India, within the Murshidabad and Baikunthpur forests of Jalpaiguri beneath the leadership of Pandit Bhabani Charan Pathak.

- They were successful in forming independent governments in Bogra and Mymensingh.

- Other influential leaders of the revolt were Majnu Shah, Chirag Ali, Musa Shah, and Debi Chaudhurani.

- The end –

- Warren Hastings used his full force to subdue the revolt.

- Significance –

- The most significant feature of this movement was the equal participation of Hindus and Muslims in the uprising.

- Debi Chaudhurani’s participation signifies the women’s role in early resistance against the British.

- Anandamath, a novel by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, is based on this revolt. He also wrote a book named Debi Chaudhurani.

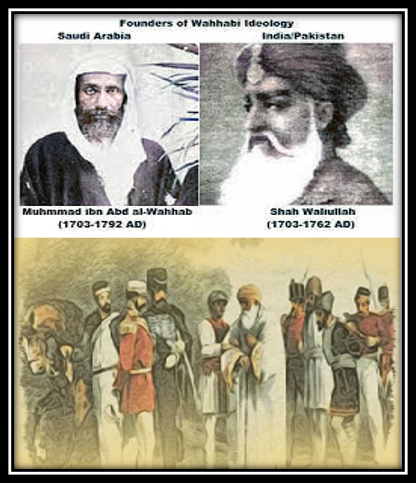

2. Wahabi Movement

Syed Ahmed of Rai Bareilly founded the Wahabi Movement. It was fundamentally an Islamic revivalist movement. He was influenced by the teachings of Abdul Wahab of Saudi Arabia and Shah Waliullah of Delhi.

Shah Waliullah or Sayyed Ahmad of Bareilly and their lesser-known followers like Haji Shariatullah of Faraizis in Bengal or Maulvi of Faizabad or Maulvi Karamat Ali of Jaunpur, all in the first half of the 19thcentury, were influenced by the Wahabi movement.

- Teachings –

- He criticised the Western influence on Islam and Islam and advocated going backto the pure form of the Prophet’s time, Arabic Islam and society.

- They concentrated their attention on the “Un-Islamic” practices prevalent among the Muslims, like the folk practices of joining each others’ festivals, modes of salutations and greetings, shared customs and etiquettes influenced by the surrounding Hindu ethos, and, above all, worship of saints as Shirk (associating other powers with Allah) and so on.

- They wanted to wean away the Muslims, especially the new converts, from the Hindu practices and replace a purified form of Islam unadulterated by “foreign influences instead”.

- The entire movement revolved around the “Quran” and “Hadis”.

- Syed Ahmed was hailed as the desired leader (Imam).

- A national organisation with an elaborate secret code for working under spiritual vice-regents (Khalifas) was set up.

- Sithana, in the northwest tribal belt, was selected as the organisation’s operational headquarters.

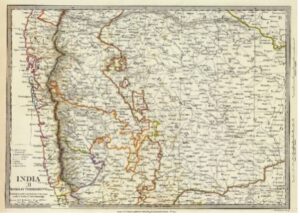

- Its important centre in India was Patna, though it had missions in Madras, Bengal, Hyderabad, the United Provinces, and Bombay.

- The revolt –

- Since Dar al-Harb (territory of war or chaos) was to be converted into Dar al-Islam (the land of Islam), jihad was proclaimed against Punjab’s Sikh kingdom.

- The English dominion in India became the only target of the Wahabi’s attacks after the Sikh King was overthrown and included in the East India Company’s dominion in 1849.

- The end –

- A series of British military operations, like the Battle of Balakot and the Ambala War of 1863, weakened the Wahabi resistance.

- Numerous sedition-related court cases were filed against the Wahabis.

- However, sporadic encounters with the authorities continued into the 1880s and 1890s.

- Significance –

- The Wahabi movement never took on the characteristics of a national movement. On the other hand, it left a legacy of isolationist and separatist tendencies among Indian Muslims. But we can see that Wahabis were crucial in spreading anti-British sentiments.

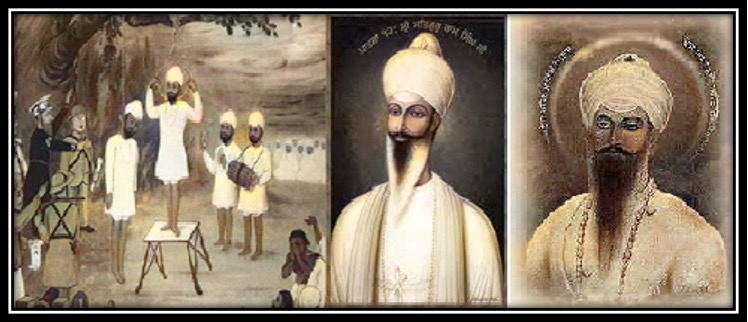

3. Kuka Movement 1840

The Namdharis are the Sikhs who believe the lineage of the gurus did not end with Guru Gobind Singh. They have also been known as “Kukas” due to their trademark style (excessive-pitched voice, called “Kook” in Punjabi) of reciting the “Gurbani”.

- Background of their revolt: –

- This movement was founded by Bhagat Jawahar Mal (also called Sian Saheb) in western Punjab.

- Baba Ram Singh, the founder of the Namdhari Sikh sect, was a significant leader of the movement after him. To unit people, the Baba Ram sign boosted the movement. It attracted the Hindus too.

- Social Teachings of the Namdhari Movement –

- Abolition of caste and other forms of discrimination among Sikhs.

- It discouraged the consumption of meat, alcohol and drugs.

- It encouraged intermarriages and widow remarriage.

- The movement made humans aware of their serfdom and bondage.

- The Political Turn – The movement was converted into a political campaign from religious purification after the British conquest of Punjab. The 12th of April 1872 is usually the official day the movement was born.

- It sought to overthrow the British and reinstate Sikh rule over Punjab.

- It promoted the wearing of hand-woven clothing and the rejection of English laws, education, and goods.

- The end – The movement was severely crushed around 1863–1872. In 1872, Ram Singh was exiled to Rangoon.

- Significance – The Kukas promoted the ideas of Swadeshi and non–cooperation long before the ideas became part of the Indian national movement in the early 20th century.

Other Politico-religious Movements

| Revolts | Features |

Titu mir in Narkelberia (in Bengal Province) Revolt |

|

| Rising at Bareilly (1816) |

|

| The Pagal Panthis (1830-1840)

|

|

Faraizi Revolt (1838-57) |

|

Moplah/Malabar Uprisings (late 19th CE-early 20th CE) |

|

Movement by the Rulers and Zamindars/Chiefs

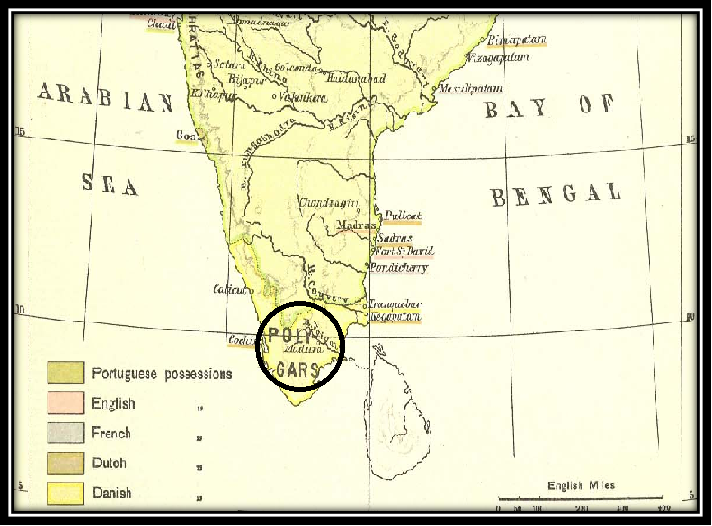

Poligars’ Revolt (1795–1805)

Poligars were the embranchment of the Nayankara system (Vijayanagara administration). They were given land in exchange for military service. However, with time, they started extracting taxes from the people. As the company’s government wanted to augment its source of revenue, it sought to control the poligars.

- In 1781, the Nawab of Arcot (Carnatic) gave administrative control of Tinneveli and the Carnatic to the East India Company.

- It caused resentment in poligars (a feudatory chief also called Palayakarars), who had long considered themselves independent sovereign authorities within their territories.

- The main centres of these uprisings were Sivaganga, Tinneveli (or Thirunelveli), Ramanathapuram, Sivagiri, Madurai, and North Arcot.

- The revolt’s first phase (1795-1800)–

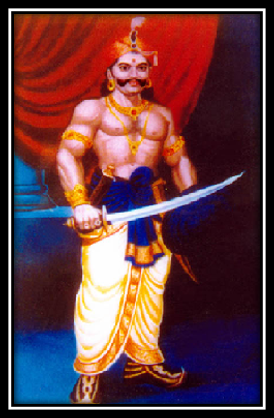

- Kattabomman Nayakan, the poligar of Panjalankurichi, was defeated by the company forces in 1799 after some initial success.

Kattabomman Nayakan

Kattabomman Nayakan

- Kattabomman Nayakan, the poligar of Panjalankurichi, was defeated by the company forces in 1799 after some initial success.

- Vijaya Raghunatha Tondaiman, the ruler of the kingdom of Pudukottai, helped the British forces.

- Kattabomman and his close associate Subramania Pillai were hanged. Soundara Pandian nayak, another rebel, was killed.

- The palayam (a small kingdom) of Panjalankurichi and the estates of five other poligars were confiscated.

- The revolt’s second phase (1801-1805) –

- The second phase shows a large magnitude of participation; it was also known as the South Indian Rebellion.

- It was directed by an alliance of Marudu Pandian of Shivganga, Gopal Nayak of Dundigal, Kerala Verma of Malabar and so on.

- In 1801, the imprisoned poligars were able to escape from the fort of

- Oomathurai, brother of Kattabomman, joined the rebellion of the ‘Marudus’ led by Marathu Pandian. They were suppressed in October The fort of Panjalankurichi was destroyed.

- Earlier, under the Carnatic treaty of the 31st of July 1801 with General Arthur Wellesley, the nawab of Arcot surrendered all the territories, including the territories of poligars, to the company in perpetuity.

- Between 1803 and 1805, the North Arcot’s poligars rose in rebellion when they were deprived of their right to collect the kaval fees or watch duty fees.

- Kaval, or ‘watch’, was a hereditary village police officer with specified rights and responsibilities. Poligars levied the kaval fees from the inhabitants of their Palayam (a military camp or a small kingdom).

- Significance –

- It ended the two-and-a-half centuries-old system of poligars, and the Ryotwari system was introduced.

- The Poligar rebellion was spread over a vast area of South India.

| Revolt | Features |

Revolt of Raja of Vizianagaram (1794)

|

|

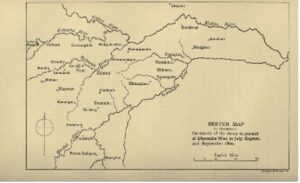

Uprisings in Ganjam and Gumsur (1797, 1835–37) |

|

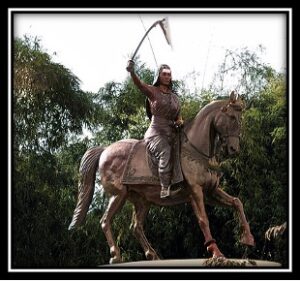

Resistance of Kerala Varma Pazhassi Raja Varma Pazhassi Raja

(1797 and 1800–05)

|

|

Rebellion in Awadh by Wazir Ali Khan (1799)

|

|

Revolt of Dhundia in Bednur (1799–1800) |

|

Uprisings in Palamau (1800–02) |

|

| Uprisings in the Haryana Region (1803-1810 |

|

Dalawa Velu Thampi’s Travancore Rebellion (1808–09)

|

|

Parlakimedi (Ganjam, Odisha) Outbreak (1813–34) |

|

Kittur rising(1824-29) |

|

| Kutch or Cutch Rebellion (1816–32)

|

|

| Upsurge in Hathras (1817) |

|

| Waghera Rising (1818–20) |

|

| Raju Rebellion(1827-33) |

|

Ahom Revolt (1828-30)  |

|

| Palakonda outbreak(1831-32) |

|

Satara disturbances(1840-41) |

|

Bundela revolt(1842) |

Oppressions.

|

Movement by the Dependents of the Rulers

| Revolt | Features |

| Revolt of Moamarias (1769–99) |

|

Bundelkhand’s Rebellion (1808–12) |

|

| Ramosi Risings (1822, 1825-26) |

|

| Gadkari Kolhapur revolt (1844) |

|

| Savantvadi Revolts (1844) |

|

- Background –

- Kings of Odisha granted paiks of Odisha heritable rent-free land (nish-kar jagirs) tenure in exchange for military(land) and policing service.

- The British occupied Odisha in 1803, and the dethronement of the Raja of Khurda reduced the power of the So, they rebelled back.

- Moreover, the British policy of high rent extortion from land, high salt tax, the requirement of payment of taxes in silver and the abolition of cowrie currency caused resentment among the citizens.

- The British disagreedwith them and installed a commission under Walter Ewer to investigate the difficulty.

- As per the commission recommendation, In 1814, the company took over Bakshi Jagabandhu Bidyadhar’s (the military chief of the Raja of Khurda) ancestral estate of Killa Rorang.

- In March 1817, the Konds tribe arrived from Ghumsar into Khurda territory to support the revolt.

- The revolt –

- Bakshi Jagabandhu Bidyadhar led an army against the British with active support from Mukunda Deva (the last Raja of Khurda), other zamindars and the Konds.

- Other important leaders of the rebellion were Dinabandhu Santra, Gopal Chhotray, Padmanabha Chhotray and Siva Nayak.

- They set fire to government buildings, killed police officers and British officials, looted the treasury, and the ship docked on the Chilika.

- British got control of Khurda by mid-1817, but the paika rebellions continued the guerrilla attacks.

- The end –

- The British army gradually crushed the rebellion by 1818.

- In November 1818, Dinabandhu Santra and his group surrendered.

- Jagabandhu was declared an outlaw and was sheltered by the Raja of Nayagarh.

- Priests at the Puri Jagannath temple who had sheltered Jagabandhu were caught and hanged.

- In 1825, he surrendered under negotiated terms.

- The British granted some concessions in the region, such as significant remissions of arrears, lower assessments, suspension of the sale of defaulters’ estates at discretion, a new agreement on fixed tenures, and different adjuncts of liberal governance.