Tribal Movement in India- Complete Notes for UPSC

Tribal Movement in India

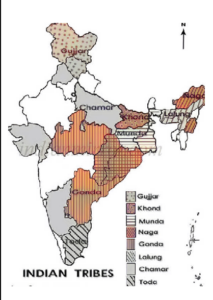

From the beginning, tribal people had lived in rural India in varying economic conditions and relative seclusion. They kept their distinct identity despite their interactions with non-tribal people. Each tribal community continued to have its own political and economic structures, as well as its own socio-religious and cultural life. Land and forests were the tribal peoples’ primary sources of production and subsistence. They were unknown to the landlordism.

The British policies disturbed their traditional systems; thus, they rebelled against them or any outsiders who infringed upon their rights.

Salient Features of the Tribal Movements

- Categorisation of enemies: They identified their enemies as outsiders (dikus), such as landlords, moneylenders, missionaries, and European government officials. But not all ‘outsiders’ were seen as enemies, such as the poor who lived by their manual labour or profession.

- Social and religious: Although these movements had a social and religious overtone, they were directed against the issues related to their existence.

- Rise of Local Leaders: These movements were led by tribal chiefs, who were generally messiah-like figures.

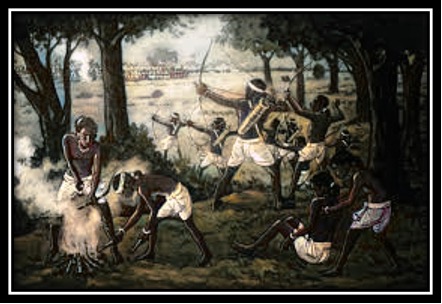

- Use of traditional weapons: The tribals fought against their enemies with traditional weapons, i.e., bows, arrows, lathis, axe, etc.

- Violent in nature: Their movement often turned violent, resulting in the killing of oppressors and the burning of their houses.

The tribal uprisings can be studied under two heads: northeast tribal revolts and other tribal uprisings.

Causes of Tribal Movements:

These tribal rebellions were sparked off by several factors, which are –

- Ownership tradition: The land settlements of the British disrupted the joint ownership tradition among the tribals and disturbed their social fabric.

- The Company government expanded agriculture in a settled form, which resulted in tribal people losing their land and an influx of non-tribal outsiders (Dikus) into these areas.

- Ban on shifting cultivation: Shifting cultivation in forests was banned, which added to the tribals’ problems.

- The emergence of reserved forests: By establishing reserved forests and imposing restrictions on the use of timber and grazing, the government increased its authority over the forested regions.

- This resulted from the increasing demand from the company for timber— for shipping and the railways.

- Exploitation by the outsiders: Exploitation by the police, traders, and moneylenders (most of them outsiders) aggravated the tribals’ sufferings.

- Hindrance in traditional practices: Some general laws were hated for their intrusive nature, as the tribals had their customs and traditions.

- Role of Christian missionaries: With the expansion of colonialism, Christian missionaries came to these regions and started interfering with the conventional customs of the tribals. As a result, the missionaries, perceived as representatives of the alien rule, were resented by the tribals.

In addition, northeast tribal uprisings have the following specific elements and reasons which set them apart from the other tribal uprisings:

- Socio-cultural links: The north-eastern tribes shared socio-cultural ties with countries across the border. However, they were not completely integrated with British rule’s political and economic system. Their movements didn’t concern with the nationalist struggle.

- Type of Polity: They aimed at political autonomy within the Indian Union or complete independence.

- Nature of Revolt: Their movements were not forest-based or agrarian revolts, as these tribals generally controlled vast areas of land and forest. Moreover, they were the majority in the region and were relatively economically and socially secure.

- The movements in the northeast tended to be revolutionary or revivalist rather than tending to Sanskritisationas other tribal movements generally were. Sanskritisation movements were utterly absent in them. For example, the Meiteis started a campaign during Churchand Maharaja’s rule (1891-1941) to denounce the malpractices of the neo-Vaishnavite Brahmins.

North-East Tribal Movements

Mainland Tribal movements of India:

The revolt by Raja Jagganath (Pahariyas revolt of 1778)

Background

-

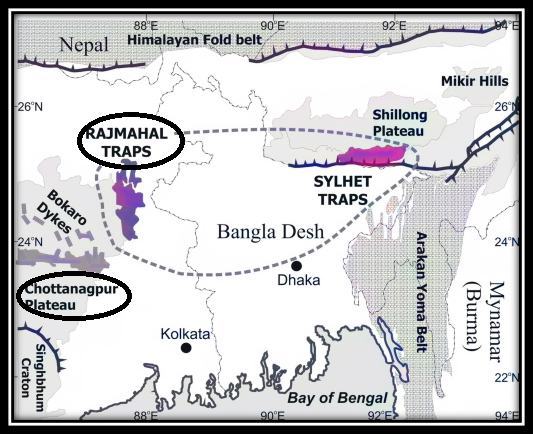

- Pahariyas are the tribals who live around the Rajmahal Hills in in the north-eastern Chhota Nagpur Plateau.

- They lived on food produce and practised shifting cultivation.

- They were hostile to outsiders but regularly raided the agriculturalists in the plains in the year of scarcity.

- Zamindars in the plains regularly paid tribute to the Pahariyas’ chief to buy peace.

- But during the last decade of the 18th century, the British policy of forest clearance for new agricultural land disrupted the peace between the Pahariyas and the settled cultivators.

- Extensive agriculture led to a scarcity of forest and pastureland for the Pahariyas.

- There were more frequent raids during the famine of the 1770s.

- The British resorted to brutal hinting and killing the Pahariyas.

The Revolt

-

- In 1778, the Pahariyas rebelled under the leadership of Raja Jagganath.

The end

-

- In the 1780s, the British initiated a policy of appeasement.

- Pahariyas chiefs were given an annual allowance to ensure that their men conducted themselves appropriately.

- But few Pahariyas continued to rebel against the outsiders or

Jungle Mahal Revolt or the Chuar Uprising (1766- 1809)

Background

- Jungle Mahals was a district formed by British possessions and some independent chiefdoms between Bankura, Midnapore and

- The literal meaning of Chuar, Chuad or Chuhad is barbaric, uncultured, or robber. During British rule, the Bhumijas (Bhumjis) of the Jungle Mahal area were called chuar.

- Bhumjis are tribals of the Munda ethnic people who speak the Munda language.

- These people were farmers and hunters; some worked under the local zamindars.

- They held their lands under feudal tenure but were not firmly attached to the soil, as they were ready to change from farming to hunting at the order of their jungle chiefs or zamindars.

- These jungle zamindars used to hire paiks (guards who policed the village) from among the Chuars.

- The head paiks were known as the sardars.

- The Chuar uprisings occurred in phases, each with its characteristics, leaders, and epicentre.

The First Revolt

- In 1766, against the British demand for high revenue, Raja Jagannath Singh led bhumijas against the British in

- He was the zamindar of

- Raghunath Mahato led the revolt in 1769

Jagannath Singh and Raghunath Singh

The Second Revolt of 1771

- In 1771, the Chuar sardars like Subla Singh of Kaliapal, Shyam Ganjan of Dhadka and Dubraj started the rebellion.

- Baidyanath Singh and Raghunath Singh later led it.

The Third Revolt of 1798-99

- The revenue and administrative policies of the East India Company and the police regulations imposed in rural Bengal made hiring local paiks redundant as they came to be replaced by professional police.

- Durjan (or Durjol) Singh, the zamindar of Raipur in 1798, led the aggrieved paiks and ordinary Chuars to join hands with the jungle zamindars in the Chuar rebellion of 1798.

- Other prominent leaders were Madhab Singh( brother of the raja of Barabhum), zamindar of Juriah, and Lachman Singh of Dulma.

- In early 1799, Rani Shiromani of Karnagarh attacked and looted all the company’s weapons in the fort of Karnagarh.

The Ganga Narayan Singh Revolt of 1832-33

- He led Bhumij’s revolt against the British, based in the Midnapore district’s Dhalbhum and Jungle Mahal areas.

Ganga Narayan Singh

Kol Mutiny (1831)

Background

-

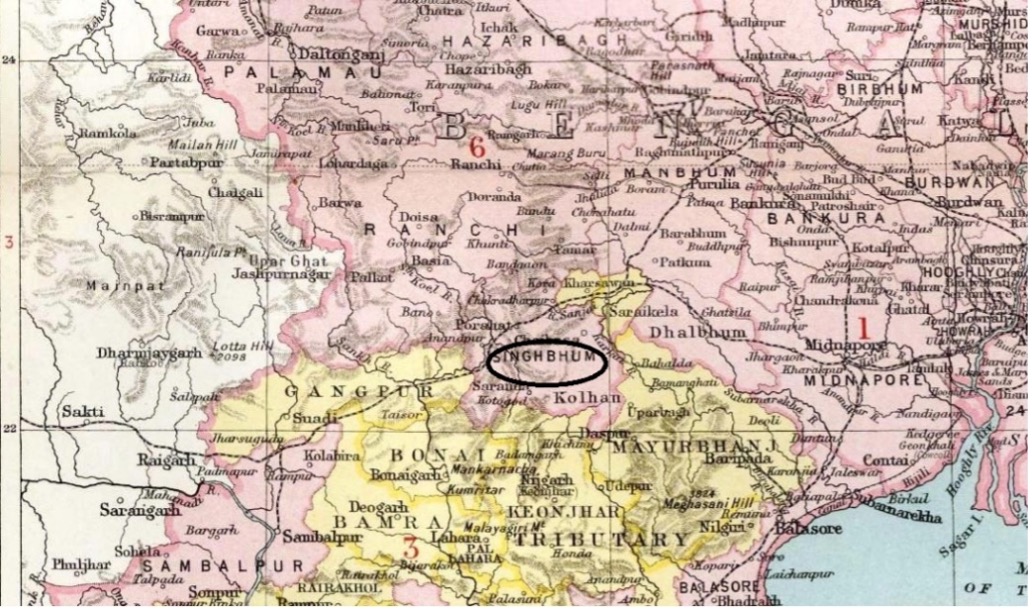

- Kols are inhabitants of Chhotanagpur(Ranchi, Singhbhum, Hazaribagh, Palamau, and the western parts of Manbhum).

- The new British law aided the transfers of land from Kol headmen to outsiders(Hindu, Sikh and Muslim farmers and moneylenders) who were oppressive and demanded heavy taxes.

- Moreover, the British judicial and revenue policies harshly affected the conventionalsocial situations of the Kols.

The Revolt

-

- In 1831, their resentment led to an uprising by Buddhu Bhagat, Joa Bhagat and Madara Mahato.

- The tribes such as the Hos, Mundas and Oraons joined them.

- They killed or burnt about a thousand outsiders.

The End

-

- The modern weapons of British forces overpowered them.

Ho and Munda Uprisings (1820–37)

- Ho is an Austroasiatic Munda ethnic group of India. Ho means Human in their language.

- After the battle of Buxar, Chhota Nagpur was ceded to the EIC as a part of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa provinces. The raja of Singhabhum requested protection from British subjects at Midnapore.

- The Raja of Parahat led his Ho tribals to revolt against Singhbhum’s occupation around 1820.

- In 1827, the Ho tribals were forced to submit.

- However, later in 1831, they rose again, joined by the Mundas of Chhotanagpur, to protest the newly introduced agricultural revenue policy and the entry of Bengalis.

- Though the revolt was extinguished in 1832, the Ho operations continued till 1837.

Tilka Manjhi revolt (1770-1785)

Source Tilak Manjhi: One of India’s first freedom fighters | SabrangIndia

Background of Tilka Manjhi

-

- Tilka Manjhi was born as Jabra Paharia led the revolt against the British in the Santhal

- He rebelled against the policy of exploitation, extortion, and harassment by revenue collectors, police officers, and the agents of the landlords.

- Moreover, the famine of 1770 led to starvation in the region and consequent protests, a situation to which the British responded with more oppression.

The Revolt

-

- He came down from the hills of Sultanganj, attacked the British boats in the river Ganga and looted their treasury.

- He distributed the loot among the poor, which increased his followers.

- His guerrilla attacks also included Santhal women.

- In 1778, he captured Ramgarh’s cantonment from the British.

- In 1784, he attacked Bhagalpur and fatally wounded the British magistrate of Rajmahal, Augustus Cleveland, with his arrow.

The end

-

- He was captured and hanged to death in 1785 in

The Santhal Rebellions (1833; 1855–56)

Background

-

- Between the late 1770s and early 1780s, the British encouraged the Santhals to move into the Rajmahal area from the region of Cuttack, Dhalbhum, Manbhum, Hazaribagh, and Midnapore.

- They gave up their nomadic life by clearing the forest and growing crops.

- This favoured the British as they wanted an extension in the cultivated land for more revenue.

- But the settlement of Santhals in the foothills of Rajmahal brought them into conflict with the Pahariyas.

- This conflict signifies a battle between the hoe and the plough (during 1833): the hoe symbolising the Pahariyas, who used the tool in shifting cultivation and the plough standing for the Santhals, who used it for settled agriculture.

- Damin- i-koh –

- The British negotiated a compromise between the two groups by forming the Damin- i-Koh in 1832-33. (Damin-i-koh is a Persian term meaning the outside edges of the hills.)

- A section of land near the foothills was designated as belonging to the Santhals; they were to live there, engage in plough-based agriculture, and establish themselves as settled peasants.

- The Pahariyas were practically forced to retreat into the higher hill tracts.

- The Permanent Settlement Act of 1793 brought high tax demand by the Company government.

- They borrowed money to pay these demands.

- But the diku moneylenders charged high-interest rates and, when debts remained unpaid, took possession of the land.

- Gradually, zamindars were taking over the Damin

The Revolt

-

- By the 1850s, the Santhals rebelled against the zamindars and the moneylenders, which was soon converted into rebellion against the British colonial state.

- The Santhals called the revolt ‘hul’, meaning a liberation movement.

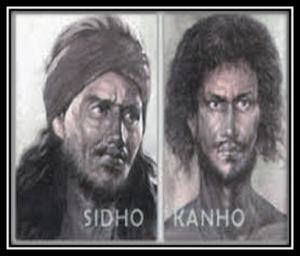

- Under Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu(two brothers), the Santhals proclaimed an end to Company rule and declared the area between Bhagalpur and Rajmahal autonomous.

- They communicated by using sal branches.

- Phulo and Jhano Murmu, Sidhu’s and Kanhu’s sisters, entered the enemy camp under cover and killed soldiers.

The End

-

- The British suppressed the rebellion by 1856, and Sidhu and Kanhu were killed.

- Santhal Pargana was formed from the districts of Bhagalpur and Birbhum.

Some of the other mainland tribal movements:

| Revolt | Leader/s | Tribes/Region | Causes |

| Khond Uprisings (1837–56)

|

Chakra Bisoi

|

Khond, Ghumsar,

Kalahandi, and other tribals of Odisha to the Srikakulam and Visakhapatnam (Andhra Pradesh) |

1.The suppression of human sacrifice by British laws.

2.Introduction of new taxes 3. The entry of zamindars into their areas. 4. Konds were later joined by The Ghumsar,kalhandis and so on 5. With the disappearance of the chakra bison, the uprising ended. |

|

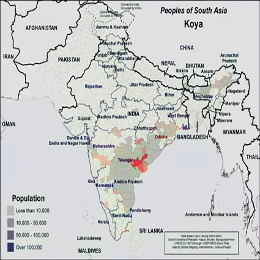

Koya Revolts (1803, 1840, 1845, 1858, 1861-62, 1879–86)

|

In 1879–80 under Tomma Sora and in 1886 by Raja Anantayyar |

Koya and Khonds tribe of Eastern Godavari (modern Andhra) |

1. Exploitation by police and moneylenders.

2. Introduction of new rules. 3. Loss of their customary rights over forest areas. 4. After Tomma Sora’s death, Raja Anantayyar organised another revolt in 1886. |

| Bhil Revolts (1817–19, 1825, 1831)

|

Seva Ram in 1825 | Bhils of the Western Ghats in the hill ranges of Khandesh | 1.Economic distress due to famine.

2. Misgovernance. 3.Outsiders’ oppression. |

Koli Risings (1829, 1839, 1844–48)

|

Kolis of Ahmednagar district in Maharashtra | The company’s rule brought unemployment and the dismantling of their forts. |